Today’s briefers carry on a proud history of service as they connect with over 80,000 people a week. But should GA be proud—or abashed—at what “service” means today?

The tale used to go like this: It’s a dark and stormy night. You’ve spent the last 500 miles bouncing around the inside of an unbroken cloud, living in a world of round instruments 20 inches in front of your face. You’ve kept the attitude indicator blue-side up, the altimeter’s 100s hand at 12 o’clock, and the CDI needle within a degree or two of center as VOR after VOR has ticked by. On departure, the TAF for your destination was sickeningly close to minimums—but that information is hours old.

With an auditory nod from ATC, you change frequencies and call up Flight Watch. Somewhere at a desk below you in the murk, a fellow human being retrieves something vital that he has and you don’t: information. Between the two of you, the miasma around you parts (at least in your mind’s eye) and a plan to end this flight on the desired pavement forms.

If you were a cloud flier before about 1990, then somewhere on the way some Flight Service Specialist probably saved your bacon. Or, at the very least, helped you keep it from getting burnt. But that was before the ubiquity of the internet. That was before datalink weather. That was before Flight Service was put out for contract. And those three things changed everything.

Back to the (FSS) Future

In 2006, one year after Lockheed Martin (LM) took over management of Flight Service from the FAA, we visited the Leesburg, Va., hub, still under construction (“AFSS Futurama” November 2006 IFR). The goal was to see what this promised system, called FS21, would really offer. We were welcomed in, our questions were answered and we left skeptical—but hopeful—that LM would not only pull off this grand undertaking, but would deliver on a promise for even better service than before.

Many industry insiders had hope. Then-AOPA-President Phil Boyer, who was a major booster for the project, wrote, “After spending 90 minutes getting an advance look at a 21st century flight service station and asking hard questions, all I can say is, Wow! On the basis of what Lockheed Martin will deliver under the contract, pilots are going to be much better served and much safer.”

By 2007, Phil Boyer would pen an editorial titled “Egg On My Face” after multiple meltdowns of the system. In October of 2008, we at IFR looked again (“Is FSS Getting Better?”) with another visit to the eastern hub, then in full operation, and a survey of pilots. The takeaway was three-fold: The system was basically working in that pilots could get through to a briefer without needing roll-over minutes on their cell plans; over 50 percent of those surveyed felt quality and safety had gone down, not up; and LM was perfectly satisfied with how things were going.

Last year we put out a call to readers of this magazine and our sister website AVweb.com as a how-goes-it on Flight Service. The results were similar to the 2008 survey: Many pilots were perfectly happy with Flight Service, but a majority of those who responded expressed either frustration, or had stopped using flight service altogether. We also saw some disturbing complaints from controllers about how LM’s system impeded the filing of PIREPs and from pilots about getting clearances remotely.

We asked for a new tour and interview. Initially, LM agreed, but asked to see our gripes and our survey. We de-indentified the data and sent it along with the questions. The planned visit was first rescheduled—and then rescinded. By November of 2011, the official brush-off was: “Due to the nature of some of our work or customer relationships, at times we have to decline external engagements for various reasons. At this time we still are not able to grant interviews or tours, however, please feel free to check back at a later time.”

We did check back and got radio silence—until just before this article went to press. So now we have an invitation to visit about the same time you read this issue. We’ll let you know what we find and what they say in a later article. Until then, let’s get up to speed on where it seems Flight Service stands today.

The Beefs

The gripes with Flight Service under Lockheed Martin fall into three general categories: Areas where LM seems not to be living up to its promises or contractual requirements; areas where LM is meeting the contractual requirements but pilots are frustrated anyway (we are a fussy lot); and areas where pilots would like LM to provide something not explicitly demanded by contract but they feel is a service LM should offer.

In fairness, LM is really only bound by the first category. But there are issues here. The biggest beef is that there has been a near-complete loss of local weather knowledge. One of the promises with LM’s takeover was that briefers would be trained in geographic areas so a pilot calling in would be matched with a briefer knowledgeable in that region.

This system exists, but our sources (and experience) say it isn’t working. Not only do briefers not know the local weather phenomena any better than most of the local pilots, they don’t know local fixes, airports or geography. So there’s a tedious, phonetic, spelling out of everything on top of generic weather interpretation.

LM promised that calls would be answered within 20 seconds—and they are. But pilots tell us that doesn’t mean service is only 20 seconds away. Getting IFR clearances from remote locations seems still to be a problem, with occasional waits of over 20 minutes after contact to get the clearance. Sometimes the person answering the dedicated clearance-delivery number doesn’t know how to get the clearance and has to connect with another specialist. Some pilots tell us they have gotten so frustrated they launched illegally into IMC just to get the clearance in the air. This is not an improvement in safety.

That said, some survey respondents tell us LM is aware of the issue: “A few years ago, there was an unacceptable wait time. I made a complaint and actually got a call from a supervisor. He explained, apologized and corrected, as well as giving me his number to call if the problem persisted. I was impressed with prompt follow-up.”

However, a controller who answered our survey shed light on the issue from another angle, and we plan to ask LM what they are doing to correct it:

“When we are called for a clearance and are unable to give one right away, they hang up the line. We do not have a direct-dial line; we dial into the pool just like pilots, and waste time waiting for them to track down the correct briefer. They also have limited to zero knowledge of common fixes in our airspace, so a readback includes painfully listening to them phonetically spell each fix. They have no way of muting their frequencies, so if someone is calling them, we cannot hear a damn thing they say, and they need to start all over again.”

The direct-dial issue also interferes with PIREPs getting into the system: “I’m an air traffic controller. When I receive a PIREP, I have to call FSS to put it into the system. I frequently have to drop the call to FSS to communicate with pilots. That means the PIREP doesn’t get into the system. This is the computer age; why isn’t there an electronic PIREP form that I can access via the FAA intranet?” Lost PIREPs because the controller is put on hold? We’re going to call that another area where safety has not improved.

Speaking of the computer age, one promise of the FS21 system that LM would create an internet portal where pilots and briefers could look at the same screens while they gave briefings. That simply hasn’t materialized. In fact, the Flight Service website (www.afss.com) is almost static. Perhaps telling is the number of articles posted in the “News & Notices” section: six in 2007, 25 in 2008, 27 in 2009, one in 2010 and none in 2011. There are three as of this writing in 2012, so perhaps there is hope here.

Another promised feature was text messaging to pilots when there was an important update after their briefing was done. We’ve never heard of anyone getting this service, although one survey respondent told us a briefer actually called him back with just such an update. Now that’s service we applaud.

Contractual Straightjacket?

We saw multiple complaints about specialists clogging up briefings with information the pilot deemed useless. This is particularly a problem with airborne contact: “When I’m in the soup and call to get an update on convective activity, and the controllers are active with other traffic, it kills me to have to listen to a mandatory lecture on Convective SIGMETS that may be over 200 miles before my location when all I want is to know what is right around me.” Another told us that LM’s “readback policy on PIREPS is so cumbersome that I have stopped giving PIREPs.”

Yet these items are requirements of either the FAA contract or LM internal policies. When LM was still talking to us, they made the same point: “Some of the complaints might be related to the difference between what we’re required to do versus what the pilot wants.”

But don’t we have a right to get what we want from Flight Service? Contracts can be renegotiated, especially when there’s evidence something deemed to improve safety is actually detrimental.

We don’t argue one bit that LM isn’t meeting its contractual obligations—by the numbers. But what made Flight Service great once upon a flight time wasn’t captured anywhere within the numbers. It was in the need fulfilled.

This pilot’s comment was echoed by many others: “When the briefer has good, local knowledge and weather-interpretation skills, talking to Flight Service is a great experience, but if not, then it’s just the same as getting it from a computer. It varies a lot from briefer to briefer. Ideally, all briefers would provide that value-add of judgment that a computer does not have.”

That’s not something that can be mastered by every specialist, but it is something that can be rewarded. One of our questions for LM is how briefing quality is judged. We know of no easy way for a pilot to commend a good briefing, or tag one that just parroted the weather.

It’s also unclear to us what incentives a specialist—or LM itself—has to provide better service. We wonder if there is any disincentive as well. Does LM fare better financially if fewer pilots use the system?

LM couldn’t give us detailed responses in time for this article, but they were able to say a few things. They tout that they meet or exceed all 23 of the FAA’s performance measurements and point out that over 90 percent of their staff now has over four years of job experience. They feel this proves the local weather knowledge is quite high. They say there are new services in the works. We hope to hear more about those when we get that planned visit.

Irrelevance or FS21 2.0?

At the core of this issue is the question of what we really want from Flight Service in the 21st century. This pilot’s comment on our survey is quite telling: “I don’t understand all the FSS bashing. I have had much better service since LM took over than I ever did from the FAA. I have been flying for 48 years and I fly IFR on 90 percent of my flights. Phone filing is as quick and easy as anything else. However, I usually get on the ADDS website in the morning to get a good, overall picture. If I fly a couple hours later, I’ll make a quick phone call to file and see if anything has changed. Of course, downlink weather has changed the situation as much as anything.”

So the pilot is happy with Flight Service, but he gets his own weather picture primarily from the internet and datalink in flight. Our opening story of weather charts and reports only in the hands of meteorologists, the 500-mile trip flying blindly through the soup, no access to file flight plans other than Flight Service—that’s all ancient history for a majority of pilots.

We know there are some great people working at LM’s Flight Service, but they are working mired in yesterday’s paradigm. Those satisfied with a service that merely fills in the gaps where today’s technology can’t quite reach are probably satisfied with today’s Flight Service. Those only looking at the numbers served and wait time for answered calls might be equally happy.

But for those who used to rely on Flight Service and almost never use it today—almost 50 percent of our survey respondents—the service has become irrelevant. Paying $190 million a year to simply fill in the gaps seems a poor allocation of funds.

Could we get the FAA and LM to offer something more relevant to today’s pilots without leaving anyone on the trailing edge unserved? We don’t know, but we hope to find out. Your reading of this piece may come just before our visit, so feel free to email us any further questions you have.

We’ll be sure to ask .

A sea change in access and savvy?

The over 1000 pilots who completed our survey represent an admittedly skewed sample. These were people self-motivated to answer our call and probably over-represents the disgruntled masses. But two sets of statistics we find telling even with that caveat, and they may be at the heart of the divide between the satisfied and the unhappy when it comes to today’s Flight Service.

Even within our survey respondents, 85 percent routinely used Flight Service for briefings before the advent of the internet. Only half of those same pilots use FSS regularly today. Among those who use FSS sometimes or rarely, the runaway comment was that FSS was only used when phone access was the only source of weather information available.

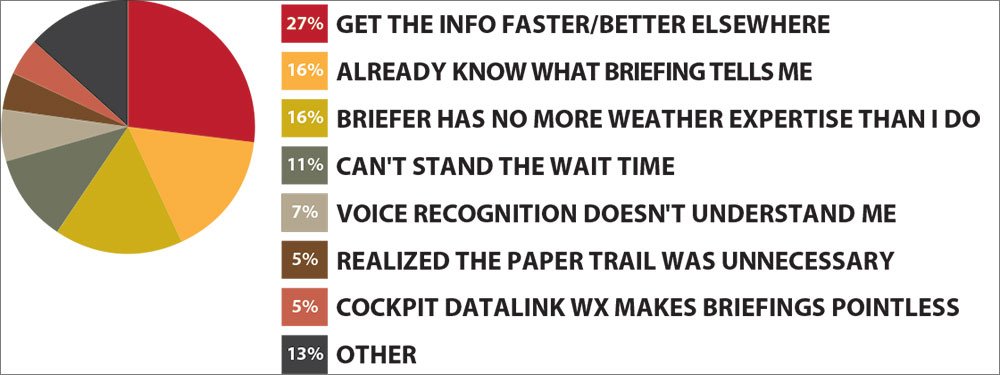

Also telling were the reasons these pilots weren’t using Flight Service for briefings anymore. The top reason, at 27 percent, was that the pilots could get the same information faster or better somewhere else. The next two reasons, at 16 percent each, were versions of the briefing not offering any gain in information or expertise. Put these three together and you get 59 percent of the pilots—almost all of whom used to regularly use Flight Service—reporting that a modern briefing provides no value-add over what they can do for themselves.

We can’t say Flight Service has become irrelevant for over half of the entire pilot population, but the services it offers are clearly out of sync with the current reality for a large portion of the flying public. Those pilots are getting nothing for their (contracted out) tax dollars. —Jeff Van West

A brief history of Flight Service

The infrastructure we call Flight Service really dates back to 1920 and the first intercontinental air-mail route in the U.S. The 17 primary landing fields had Air Mail Radio Stations (AMRS), where operators—even called “specialists” back then—made local weather observations and relayed weather to other operators. (Radios in the airplanes? Are you kidding?) Some specialists made their own forecasts. They also slung bags when the planes came in and routinely maintained (or even built) their own radios.

By 1927, the AMRSs were renamed Airway Radio Stations and became part of the Bureau of Lighthouses under the Department of Commerce. The services were open to any pilots who could call by air-to-ground radio or who landed and walked in the door. In 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) took over the functions, and during WWII women joined the service. In 1958, the FAA was created, and by 1960 the Flight Service Station was born.

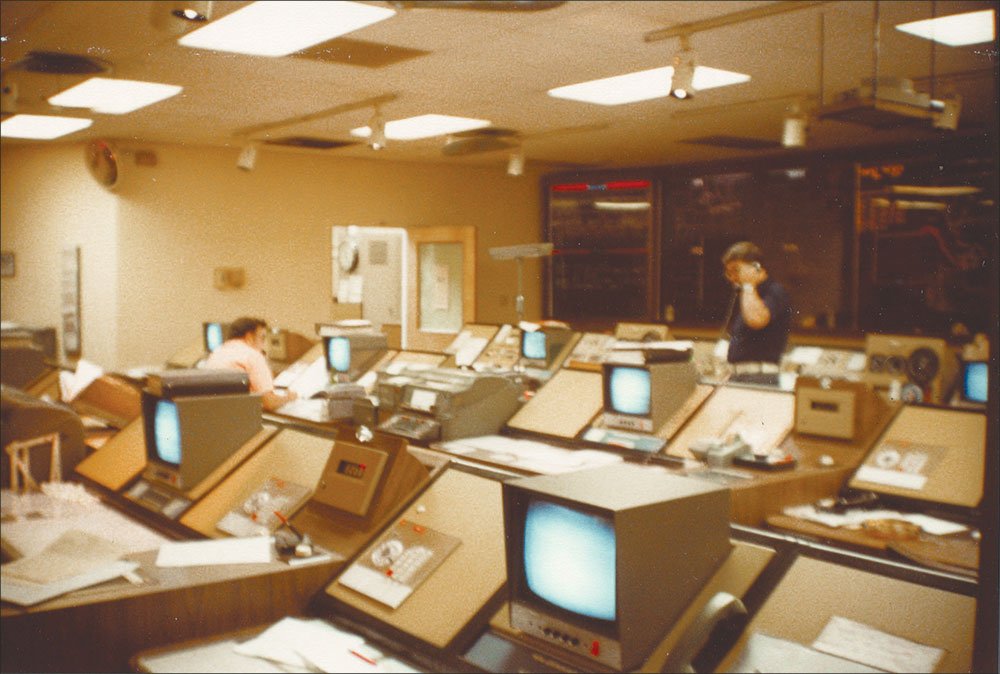

Even though relaying weather information was a task from the first days, it wasn’t until 1961 that the FAA pooled resources with the National Weather Service to train specialists as pilot weather briefers. Briefings and other services were now available by radio, phone or in person. FSS was the poor cousin in terms of funding and equipment for many years, but got a boost in the 1970s when automated systems came online with actual computer screens replacing paper teletypes still in use. This morphed through several systems culminating in something called Operation And Supportability Implementation System (OASIS). En Route Flight Advisory Service (Flight Watch) was also a product of this time, designed to offer specific weather support to pilots in flight. The goal was directly reducing weather-related accidents, and it seemed to work.

The ’70s also saw Flight Service specialists become part of the controller’s union (NATCA) and get the power of NATCA’s bargaining clout. While a good deal for the specialists of the day, that move may be what did in FAA Flight Service. Well-paid specialists at facilities nationwide (over 400 at its peak) meant a mammoth upkeep cost for the FAA. Just like the pay crisis with ATC, the agency looked for a way to cut costs. In 2005, Lockheed Martin took over the then-58 facilities as the private contractor managing the $2 billion deal to run Flight Service for the next 10 years. Except in Alaska, that is, where the function was deemed too essential to flight safety. A telling exclusion, that.

What happens in 2015? We’re not sure, other than the certain fact that Flight Service won’t come back into the government fold. —Jeff Van West

(Special thanks to atc-history.org for contributing background info and photos.)

Jeff Van West is editor of IFR. On the rare occasions he calls Flight Service he’s sure to use someone else’s phone so they don’t know it’s him.