For many pilots, summer means fly-ins, more flying and searches for the best $100 hamburger. It also marks the end of powerful jet streams and large, organized weather systems that cross the United States from one end to the other. By the time June rolls around, all that stuff shifts north and becomes a problem for our Canadian friends. But, that also gives them four months of mild summer temperatures, so don’t feel too bad for them.

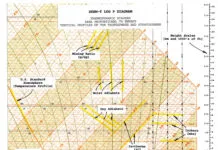

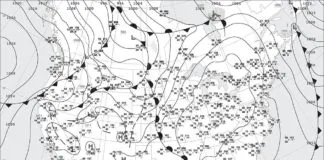

So what exactly do we have in the United States? We can distill it down to three main features. First there’s the large Atlantic Bermuda high, covering the eastern half of the country. Second is the cool Pacific high, which maintains a tenacious foothold on the West Coast. Finally there’s the broad thermal low located between the Sierra Nevadas and Rocky Mountains, strongest by far over Arizona. It’s driven mostly by intense solar heating.

A —The Northeast

Summer weather is normally good in the northeast U.S., but the rugged terrain, absent any mid-level cap, and the abundance of rich moisture means that mornings surrender to disorganized showers and thunderstorms in the afternoon, and those can temporarily reduce ceilings and visibility.

Also, the jet stream activity and storm tracks in Canada keep fronts close by, and during the summer they do occasionally push directly into the Northeast. When this happens, it means widespread squall lines, severe weather, and IMC north of the fronts. Southeastward-moving cold fronts are especially notorious for triggering severe weather, as this drives storms directly into the moisture field and maximizes storm inflow. Be on guard when you fly in the Northeast, check the TAFs often, and look for trouble anytime the general upper-level winds shift from westerly to northwesterly.

One well-known annoyance of flying in the northeast United States is haze. The vast majority of this haze has been found to originate from sulfur dioxide emissions in a Pittsburgh-Detroit-Chicago-Cincinnati box. The haze can ultimately spread anywhere across the eastern half of the country.

If you follow the day-to-day low-level charts, you can get an idea of where this haze is moving and where to expect it. For the most part it’s just an annoyance and makes it hard to see traffic, but the true danger is at night. Thick haze will mask the visible horizon and can quickly bring on episodes of spatial disorientation.

B—The Southeast

Patterns across the southeast United States during the summer are sharply tropical. Nighttime is calm with patchy fog and scattered stratus, giving way to bright blue weather during the morning and then scattered afternoon thunderstorms.

Days out, there’s no way to accurately predict which airfield will get rain and which won’t. However, it is often possible to narrow it down up to 12 hours in advance by closely examining surface observation charts, satellite and radar images for weak boundaries and old, forgotten fronts. (Thunderstorms love to congregate on any available boundary.)

If you’ve compared this map to the spring patterns we discussed in the last issue, you might notice that the pervasive Bermuda high has shifted north, allowing some east-west isobars to appear in the Gulf of Mexico. This marks a major change in the pattern that emerges by August. When this happens, the mean tropospheric flow at places like Houston, New Orleans, and even Atlanta flip-flops to easterly instead of westerly.

What does this mean for you as a pilot? Be aware of the winds aloft, because those steer the thunderstorms. That cluster of storms just east of you that’s normally not a concern might actually be on you in a few minutes.

C—Southern Plains

Weather in the southern plains during the summer is dominated by VMC and persistent southerly winds. Early June is the tail end of the spring thunderstorm pattern, and most thunderstorms are found along the dryline in the Texas Panhandle region or along stagnant fronts in northern Oklahoma and Kansas. In an active weather pattern, storm areas will expand, typically affecting Dallas, Austin and Oklahoma City during the early evening and Shreveport and Houston in the wee hours of the morning. Initial activity can be quite severe with hail and tornadoes.

Late June brings a transition to July’s warming mid-level conditions that suppress most of the organized thunderstorm activity on the Great Plains. While seemingly random “popcorn storms” can occasionally be found anywhere across the region, most storms now focus on the Rocky Mountains of New Mexico and West Texas, and along the Gulf Coast in places like Houston and Corpus Christi. If you’re arriving at those terminals and they’re rained out, a half-hour wait often finds them in good condition again. These rainstorms normally surge northward, dissipating at dusk.

There’s little change in August, but the deep easterly pattern sometimes affects parts of Texas and brings tropical weather. This can result in anything from partly cloudy skies to poor weather as upper-level troughs and tropical disturbances rake the area.

D—High Plains

June and July mark severe weather season in eastern Colorado and nearby parts of the High Plains. This means you’ll want to be especially attentive to Storm Prediction Center outlooks and TAF updates. Depending on the pattern that’s in place, you’re likely to see storms develop along the Front Range by early afternoon, moving across Denver and Cheyenne during the afternoon and to points eastward during the evening. Rich, moist air is often available to help the storms produce a lot of hail, gusty winds, textbook microburst conditions, and an occasional tornado. Give these a wide berth.

The pattern changes very little in July and August, but it becomes more common for storms to remain confined to the mountains. The severe weather risk also gradually diminishes.

E—Southwest deserts

The best flying weather in the desert southwest is early in the summer. Skies are clear and visibility is usually unlimited, but due to the strong heating, you’ll get bounced around quite a bit unless you depart quite early. High temperatures also put you on the wrong side of density-altitude concerns.

July marks a change as the Southwest Monsoon develops. The strengthening thermal low brings an infusion of moisture from southerly sources like the warm Gulf of California, and southeasterly sources like the fringe of the Bermuda High.

This moisture initially appears around Tucson, Douglas and El Paso and builds northwest into Phoenix, Flagstaff, and later around Las Vegas and into Utah. Most of the storms initially form over the highest peaks and the Arizona Mogollon Rim, but as the monsoon strengthens in late July and August, storms become more widespread and are found at more northerly locations.

These storms normally dissipate by late evening, leaving broken layers of mid-level clouds and cirrus overnight. They rarely bring hail or tornadoes to airfields, but they do frequently produce damaging winds exceeding 70 knots. In July 2014, downburst wind at Davis Monthan AFB (Tucson) flipped two parked F-16s onto one another. Considering these planes weigh 20,000 pounds, imagine what that wind could do to your unsecured 1800-pound Cherokee.

F—California

Heating hits the Mojave Desert and San Joaquin Valley in full force as summer arrives. This means that the thermal low, normally found in Arizona, often has a spur extending northwest through central California. In these interior regions, temperatures occasionally exceed 100 degrees F, with exceptionally dry weather and good VMC.

However if you compare this map with last issue’s spring patterns, you’ll see that the pressure gradient along the California coast is even stronger. This is because the thermal low has strengthened, and so has the cool Pacific high, increasing the pressure differential. Thus, coastal regions experience a much more persistent northwesterly onshore wind. This often drives shallow stratus layers eastward through coastal gaps during the night hours, which can be stubborn to dissipate during the day. Be wary of this hazard and check the TAFs frequently if you’ll be flying overnight to anyplace along the coast or just a bit inland.

As moisture increases during the summer, thunderstorms become very common on the mountain ranges, particularly the Sierra Nevada in late July and August. This is especially common when there is a deep southeasterly flow for several days, bringing moisture northwest from Arizona. Thunderstorm bases normally range between 5000 and 8000 feet MSL, so instrument conditions are only found where heavy precipitation is occurring and conditions are often good in the San Joaquin Valley.

Visibility inland is excellent. Haze is confined mostly to the Los Angeles area, and does not normally move inland until late in the summer, when the marine layer is deeper and can move through the mountain passes. Wildfires during dry seasons can also flood the region with smoke.

On rare occasions, Pacific hurricanes can wander northward and affect the San Diego area and inland deserts. The circulation nearly always weakens by the time such systems make it this far north, due to the cold Pacific current, but they can produce marginal IMC and extensive areas of rain. August and September are the most likely months for this to happen.

G—Pacific Northwest

Much like California, the Pacific Northwest is situated between the intense Pacific high offshore and the strong thermal low that exists over the high deserts to the east. The cold Pacific air normally dams against the western side of the Coastal Range, bringing frequent IMC due to stratus and fog at seaside airfields like Astoria and Newport. Meanwhile, Seattle, Portland, and Salem are sheltered on the east side of these mountains and remain VMC. The entire pattern is occasionally interrupted by cold fronts, especially in June, and this can bring widespread rain and low ceilings to the entire region for a day or two.

A “marine push” event often occurs during the summer. This happens when the coastal air pressure differential temporarily increases and winds flood eastward through the passes, inlets, and river valleys. When this is underway, it brings IMC and marginal VMC inland to Seattle and Portland. Furthermore, the marine push acts as a kind of cold front, and can produce strong showers and thunderstorms. The marine push is checked by strong heating inland, so the fringes of this overcast are normally burned away each day.

The interior regions east of the Cascades, including Spokane and Boise, remain VMC for the most part, and rarely see any of the coastal air from the west. When enough moisture is available, high-based storms will develop on the higher terrain and move over the valleys, producing brief episodes of rain and restricted visibility during the late afternoon and evening.

H—Northern Rockies

The Northern Rockies enjoy lots of VMC in June, but the large thermal low over the Southwest deserts and the Great Basin region begins shaping the weather here. A conveyor belt of air flows slowly counterclockwise around these lows, gradually bringing increasing amounts of rich tropical air from Mexico northward. Thunderstorms become commonplace on the higher terrain by late June and July, which move out onto the valleys during the day. This means that your best flying is going to be early in the day. Navigating the storms presents a special problem since you’re probably going to be doing a lot of flying at higher altitudes, and in June freezing levels can still be as low as 10,000 feet.

One of the other concerns with the Northern Rockies is high density altitudes. Remember the “three Hs”: hot, high, and humid. Considering some rural airstrips are quite short, this can be a recipe for disaster. There’s a YouTube video of a Stinson 108 crash at Frank Church River, Idaho in 2012 that provides a vivid illustration of how density altitude surprises can bring a swift end to a flight.

I—Northern Plains

Summer months in the northern Plains are known for wet nighttime patterns. This soaking overnight rain is instrumental to the region’s rich corn harvests. Thunderstorms usually form during the afternoon in the eastern Dakotas and Nebraska, along the northwest edge of the moisture field. They also form along any fronts that are sagging southward from Canada. These storms organize after dark into clusters known to forecasters as “mesoscale convective complexes.” These systems move across Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Missouri overnight, and dissipate after dawn.

The storms are normally quite rainy and benign and generally don’t produce much severe weather, but high winds occasionally occur. On rare occasions they may produce hail and isolated tornadoes. Because of the risk from high wind, it’s always a good idea to double your efforts on a secure tiedown at places like Minneapolis, Chicago, and Oshkosh if overnight summer rains are in the forecast.

May your rides be smooth and uneventful this summer.

Tim Vasquez is a professional meteorologist in Palestine, Texas. See his website at www.weathergraphics.com. He’ll gladly exchange some of his perspective for some of yours. Any pilots in the region want some weather smarts?