With the exception of a crazed pilot bent on suicide and/or mass murder, nobody wants their airplane to hit the ground at speed. Why, then, do we continue to pilot our aircraft under control all the way to the point of impact with Mother Earth? Pros and students alike are guilty, and perhaps the most frustrating aspect of this is that these oft-fatal accidents are all preventable.

The answer begins with proper pre-flight planning to evaluate the risks and your performance. The rest is having the discipline to follow through. This may all seem obvious, but we keep crashing, so let’s see what we can do about it.

Got Numbers?

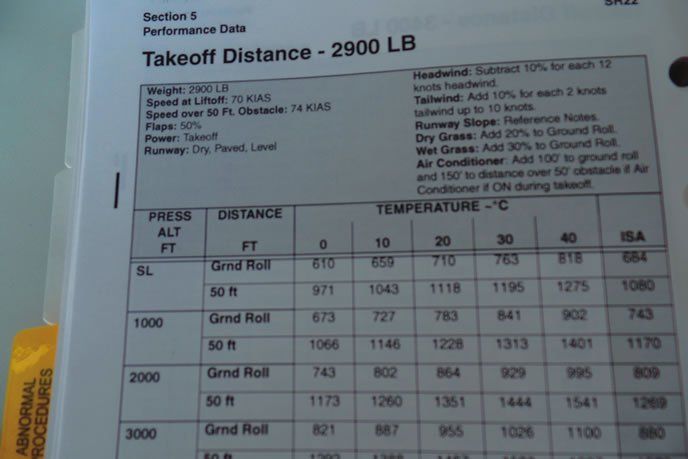

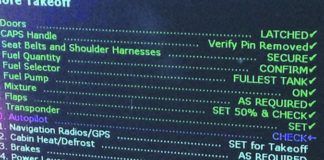

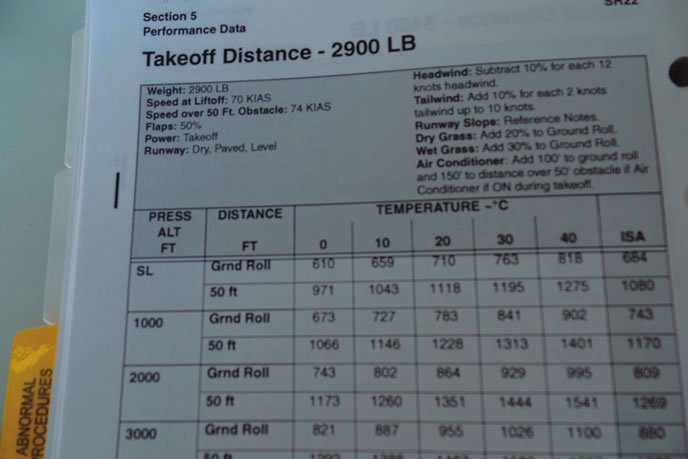

Aircraft performance is knowable from the book and the numbers are basically unchanging for specific environmental conditions. Given the aircraft and engine you have, takeoff and climb numbers are pretty much set, so there should be no surprises.

However, you can stack the deck in your favor, at least a bit. To get needed performance you can load with more or less fuel or baggage. You can even adjust the passenger count. You can adjust departure time to optimize performance from cooler temperatures. Thus, we do have information available and control over performance.

Our capability to see terrain ahead is also knowable via multiple sources, but it does change with time, and that’s the rub. TAFs and METARs give us pretty much what we need for final preparation shortly before the flight. But that doesn’t leave much flexibility in accomplishing the flight to the family reunion or business meeting whose fixed schedules are held hostage to the day-of-flight weather.

Our airplanes require air—for the wings, for the engine and for the prop. Higher air density yields better performance. We all know that density altitude increases with temperature, but, did you know that high humidity also increases density altitude? This can become a significant factor.

Alan Davis of SAFE (Society of Aviation and Flight Educators) wrote a detailed article about the effect of humidity on density altitude. He points out that the FAA has no sanctioned correction for humidity so anything you may learn about the influence of humidity on density altitude is only “for educational purposes.” Well, when it comes to safety, it’s kinda nice to be as educated as possible.

Alan explains that beyond our normal correction for temperature and altitude, “Humidity can further decrease performance from 11 percent at the higher altitudes to as much as 32 percent at lower altitudes.” He advises instructors to give students “…the rule that we have all used for ages in aviation— ‘If the airport is that marginal, for either takeoff or landing, without the humidity applied, then just don’t go!'” If you want hard numbers, Alan points to a calculator by Shelquist Engineering located at: http://wahiduddin.net/calc/calc_da.htm.

Most of us fly from runways that give us superior margins. The vast majority of U.S. public-use runways are at or below 4000 feet MSL and are 3000 feet long or longer. Also, density altitude is seldom more than 1000 feet above field elevation.

Clearly, this normally low risk can lead to complacency about density-altitude-based performance concerns, inducing us to just hop in, power up and lift off whenever it’s ready. Of course, that can bite the unwary when the temperature and humidity numbers race to 100. Consider having another glass of ice tea and examining the performance charts.

Early Weather Planning

Most of us piston-GA pilots know days, if not weeks, out when a flight is going to occur. We should start watching the weather many days before the planned flight. Non-aviation sources provide useful weather information even a week out. Thus, we can consider alternatives days in advance—we can go early, go later, use an alternative travel mode or cancel. If we wait until the day of the planned flight, most of these options evaporate.

Since reasonable long-range non-aviation weather forecasts are out there, simply look at them and factor them into your contingency planning. I use the Intellicast ap on my iPad but there are many other products available including weather.com.

Regardless of which source you like for your long-range weather forecasts, the key is to actually use them to give yourself the maximum range of planning options and not box yourself into a situation where you are tempted to push the weather beyond a prudent level simply because you “have to go.”

A Sad But Instructive Example

If you’ve been around general aviation more than a few years, you’ve likely known a pilot who died in an aircraft accident. There’s one in particular that touches my heart every time I think about it. But, we can learn from it.

The pilot was intelligent and successful in a non-aviation career. She went from student to private-instrument in 10-1/2 months. The CFIT accident occurred one week before Christmas, 2006, six weeks after her instrument checkride.

The mission was a classic example of how we advocate using GA aircraft—fly from home in Henderson, Nevada (HND) to a small Indian hospital in Chinle, Arizona (E91). She planned to spend several days in Chinle and then return home. The one-way flight time would be about two hours compared to over a seven-hour drive in a car. (How many times have we told people about the time saving attributes of flying GA aircraft? This is yet another perfect example.)

This accident also reminds us of some of the factors that give piston GA a fatal accident rate that is far worse than the airlines, the military and corporate. Our freedom to go when and where we want must be tempered by a concomitant responsibility to operate safely with all pertinent data.

The time line for this flight started about a year prior when the pilot started flight training that culminated in her instrument rating six weeks before the accident. She began general planning for the flight about two weeks out and completed the flight to Chinle, where she spent five days.

Her return to Henderson should have taken about two hours. The newly-minted instrument-rated pilot opted to go VFR because of icing concerns at IFR-required altitudes. In other words, ice and clouds meant she’d have to weave her way through the terrain. See a problem?

Shortly after departure from Chinle, she opted to divert to Winslow, as the weather was better in that direction.

She landed and checked into a motel. A mere hour and a half later, she was back at the airport doing a hurried preflight and launched again for another attempt, this time hoping to circumvent the weather by going south toward Phoenix.

Sunset was a few minutes later and she continued flying past twilight. An hour and a half after her Winslow departure, the flight ended tragically when she impacted the terrain 4600 feet.

I think the browns and tans of VFR charts for the western U.S. are quite pretty but my wife won’t let me hang them on the walls. Regardless of how aesthetically pleasing one finds those colors, they depict elevation that should raise cautionary thoughts for an aviator trying to maintain VFR on a moonless overcast night. The pilot took off at 1715 and crashed an hour and 15 minutes later. The terrain had MORAs as high as 10,900 feet and the freezing level was estimated at 7300 feet. The straight-line distance from Winslow to the point of impact should have taken 20 minutes. Thus the route flown was very circuitous, suggesting she was trying to find a way through the hills and clouds.

When Did The Accident Begin?

In your view, when did the accident sequence begin? At the end of twilight? At takeoff from Winslow? At takeoff from Chinle? The day before? Two days before? A case can be made that in accidents like this the sequence begins when 48-hour Prog Charts, 24 hour TAFs, and other (even non-aviation) weather information are not consulted in advance to discover the need for alternative plans.

This accident painfully illustrates the value of using the PAVE personal minimums checklist. (Personal, Aircraft, enVironmental, External) The “E” in that checklist for External Factors is especially important since personal schedules and the desire to accommodate family, friends and business commitments can be overwhelming.

However, if we watch the weather trends well in advance of the flight, we have it in our grasp to mitigate those external pressures by developing alternatives as we’ve discussed. In this case, there were clearly very strong personal and professional pressures to complete the mission as planned. Yet, the mission could probably have been successful with a small modification to the timing.

Another Example, Better Result

Last year, my wife and I planned for a couple of months to attend a Valentine event in Myrtle Beach, S.C., Wednesday, February 14th was to be our travel day. The weekend prior, a major storm was moving across the U.S. and I began looking closely at the outlook for the following week.

By Sunday afternoon, it was looking like Wednesday weather might be a problem. We began to consider traveling Tuesday instead of Wednesday. This was a big deal because it would upset other activities. Nevertheless, we agreed that I would look at the aviation weather on Monday and decide then.

Monday afternoon’s prog charts were very interesting. The 48-hour forecast even had freezing rain and sleet symbols that we rarely see in Alabama. That view from Monday afternoon told me that Wednesday was a clear no-go. We could either go Tuesday or maybe Thursday. Together, we decided to go Tuesday—barely 18 hours away. We updated the lodging and rental car arrangements and got the packing completed.

Tuesday morning’s final checks of the TAFs and METARs showed manageable freezing levels and winds—definitely IMC but comfortable. We loaded up and departed into a 900-foot overcast at Headland, Ala. The flight east was smooth as glass. The temperature started in the 50’s and drifted down to 40 degrees F and we had a 30-knot tailwind. Life was good and two hours later we descended through a 900-foot ceiling and landed at North Myrtle Beach airport.

Shortly after our arrival, the precipitation did indeed turn into freezing rain and sleet, but our flight had been smooth and free of drama. On Wednesday the 14th, the USA Today front page, top of the fold headline was “New storm adds misery to USA’s woeful weather; National Weather Service calls system mind-boggling.” Clearly, a bad day to fly.

Bill Castlen has been instructing since 1955 and continues to enjoy flying in interesting weather and talking about it. Thus his email:[email protected]. He is a FAASTeam Rep and lives in Dothan, Alabama.