The pilot wasn’t having much luck on his flight review. As he and his instructor were about to depart, the airport weather went from a manageable SCT006 to BKN006, requiring an IFR clearance. Since they had planned to depart VFR, they didn’t file an IFR flight plan. To top it off, the part-time tower was closed.

The pilot suggested they use the listed ground-based radio frequency to call the overlying ATC center for a “pop-up” clearance. His instructor, to our pilot’s surprise, said it wasn’t possible to do that. Not wanting to flunk his BFR, the pilot opted to wait the weather out as suggested. No sense in winning a battle to lose a war. Nevertheless, our pilot swore he’d give the center a call once the flight was over and get some real clarification.

The reality is this: pop-up clearances happen all the time, all across the United States. There are many common scenarios that I encounter regularly as an approach controller, such as flight school aircraft who departed a marginal VFR airport on a training flight and return to find their home base went IMC. Other common uses are maintenance flights that need to hop up into the Class A flight levels briefly to test pressurization or engine systems and VFR flight following aircraft that are concerned about weather conditions further down their route.

While a filed IFR flight plan is always preferred, the ATC system and the controllers who operate it are flexible enough to work without one. Like most things in aviation, though, there are a few things that can get you into trouble, and a few points to keep in mind to make it all easier.

Ground Up

Pop-up clearance requests can come from aircraft on the ground wanting to depart and from aircraft already in the air wanting to stay legal and safe. Let’s look at the pilot on the ground first, and assume you’re talking to ATC directly, not via a Flight Service relay. If you’ve got to talk to Flight Service, you may as well file an IFR flight plan with them. By the time you do that and get back to ATC, they’ll have your flight plan, so there’s no need for a pop-up.

Be as specific as possible with your position on your initial call. Don’t just say, “Lumberg Approach, this is November Three Alpha Bravo, calling on the ground.” On the ground where? Depending on my airspace configuration, I could have thirty uncontrolled airports under my supervision. “Lumberg Approach, November Six Alpha Bravo, calling on the ground at Claxton Airport.” Okay, now I’ve got your position nailed down and I can select the right transmitter.

Second, be clear about your non-filed status. There are certain words that key us into the fact that you don’t have a filed IFR flight plan, such as “requesting a pop-up IFR clearance” or—in plain ol’ English—”I don’t have an IFR flight plan filed.” If we hear these kinds of phrases, we won’t waste time hunting through the computer or our rack of flight plan strips.

Third, include your destination, and don’t be overly picky about your routing to get there. If you’re on the ground and really need a complicated routing across multiple fixes and airways, I recommend you just take the time to file an IFR flight plan.

To sum up, here’s a clean ground-based radio call: “Lumberg Approach, One Two Three Alpha Bravo is a Cessna 172, on the ground at Claxton airport, requesting a pop-up IFR clearance to KJAN at 7000.” In one call, you’ve given me everything I need to give you a clearance: call sign, aircraft type, a starting point (your current location), your request (a pop-up IFR clearance), a destination, and a requested altitude.

Some folks, even in these pages, have debated the merit of the call to request attention, as in, “Lumberg Approach, One Two Three Alpha Bravo, on the ground at Claxton. IFR request.” In most cases, this requires more dialog in the end than just stating your request initially, especially if, as in this case, it’s only adding a couple words. About the only time you’d use the call to request attention without specifically stating your request is if the controller is possibly too busy to answer you immediately.

On the Go

If you’re calling from the air, be equally specific about your location, status, and destination, but make sure to include your current altitude. “Lumberg Approach, One Two Three Alpha Bravo, a Cessna 172, ten miles east of Claxton Airport at 5500 feet. Requesting a pop-up IFR clearance to KJAN at 7000.”

The sooner I figure out which target represents you, the faster I can help you. If you’re already under VFR flight following, obviously you’re already in the system and we should know your location.

Since you’re already airborne, there are a few additional things to consider, starting with your surrounding airspace. If you’re flying through or on the border of an active MOA, we can’t give you an IFR clearance. All our IFR aircraft need to be kept a certain distance from active Special Use Airspace. We’ll have to wait until you exit the MOA before we can clear you. It’s something to keep in mind if you’re facing both deteriorating weather and SUA on your route ahead.

ATC also faces altitude restrictions. Picture a pilot scud-running under a 500 foot overcast through the mountains. In desperation, he requests an IFR clearance. The local minimum vectoring altitude (MVA) is 3000 feet; therefore the controller can’t just clear him and should be asking him, “Can you maintain your own terrain and obstruction clearance until 3000 feet?” This is a serious “cover your assets” question that reminds the pilot that up to 3000 feet, he is responsible for keeping himself away from the trees and rocks.

ATC isn’t in the plane with him and can’t see the clouds or terrain. Radars have a very limited depiction of obstacles. The pilot should not answer, “Yes” to the question unless he truly can do so. If he blindly climbs through a thick overcast, and smashes into a cliff, it’s an unfortunate tragedy, but the NTSB report will list it as Controlled Flight Into Terrain and likely show the cause as pilot error. All ATC could legally do for him until he climbed above the MVA was advise the pilot of their limitations.

The third big consideration is other traffic. ATC is required to maintain a minimum of 1000 feet vertical and three miles laterally (five for Center) between IFR aircraft. Let’s say you’re on an airway at 5500 feet and request an IFR clearance with a final altitude of 5000. There’s an opposite direction aircraft at 6000 feet, three miles directly ahead of you. ATC can’t issue your IFR clearance until either that aircraft passes behind you, or you descend to 5000 feet VFR.

Now, none of those factors should prevent you from asking for a pop-up IFR clearance if you feel you need it. However, due to these restrictions, ensure you can actually maintain VFR for the moment. Until ATC’s separation requirements for obstacles, airspace and traffic are met and you get your IFR clearance, that separation responsibility still falls on you.

Pop-up Phraseology

Okay, so you’ve told ATC you need a pop-up clearance. They’ve ensured you’re separated from conflicts. Now they’re going to give you your clearance. Does the phraseology for an unfiled IFR clearance differ from a filed one?

Nope. On the ground, you’ll still get the “void if not off by” time, a heading to enter controlled airspace, and all of the other particulars. Routing, altitudes, frequency, squawk—all of that follows the standard format.

If you’re picking it up in the air, ATC may give you a conditional clearance reference traffic or airspace. For instance, if you’re at 5500 and there’s a conflicting IFR aircraft at 6000, he may tell you, “Descend and maintain five thousand. Reaching five thousand, you are cleared to Jackson airport via Potter VOR.” Or he may give you a climb above his MVA. “Climb and maintain 5000. Leaving 3000, you are cleared direct Jackson airport.”

Pay extra attention to the routing you’re given. Since you obviously haven’t filed a flight plan, you may not get “cleared as filed” unless you gave the controller a really specific route to put into his system. The controller may have to take you somewhere unexpected. I sometimes need to route traffic over a particular fix or navaid in order to comply with a letter of agreement relating to traffic flow.

Even if flow vectors aren’t required, I may still need to vector you for traffic and airspace. In those situations, I’d include the phrase “via radar vectors” in the clearance, i.e. “Cleared to Lumberg Airport via radar vectors.” All clearances are required to have a route from the aircraft’s present position to its destination. Those radar vectors take the place of a hard route.

Buy Local

I’ve heard some pilots worry about causing ATC a headache by asking for an unfiled IFR pop-up. In reality, as long as the SUA/altitude/traffic separation requirements are met, they’re not much more complicated than a VFR flight following request. The procedure just changes slightly if it’s a local flight that’s staying within one facility’s airspace, versus a flight that’s crossing multiple facilities.

Say it’s a local flight’s first radio call. He’s either still on the ground or flying around VFR and not identified on my radar scope. I’d type in their call sign, destination, and aircraft type as I would for a VFR flight following aircraft. The only difference is that I’d add on a “+” symbol to the entry to designate it as an IFR airplane. I press “Enter” and our computer generates a local squawk code from a bank of codes that are unique to our facility. I issue the IFR clearance and…that’s it.

If they’re a local VFR flight following plane that’s already tagged up on my scope, it’s even easier. I merely need to type a “+” symbol, click their target symbol, and issue the verbal IFR clearance. Done.

By applying that “+” symbol, it changes how the radar computer treats the aircraft. A VFR aircraft can fly as low as he wants and as close to another aircraft as he wants. Now, change him to IFR, and the Minimum Safe Altitude Warning alarm will go off if he descends below the MVA and our traffic alert system—what controllers lovingly call “the snitch”—will go off and rat us out if he gets too close to another IFR aircraft.

Crossing Boundaries

For VFR flight following aircraft that are departing or just passing through my airspace, it’s only a little more complicated to make them IFR. Since they’re crossing multiple ATC facilities, their flight plan is actually stored in the National Airspace System’s database, so the information is exchanged between the facilities.

You’d think that there’s some sophisticated scheme that tells the computer which aircraft are VFR and which are IFR. You’d be wrong. In a brilliant flash of simplicity, the programmers used the requested altitude on the flight plan.

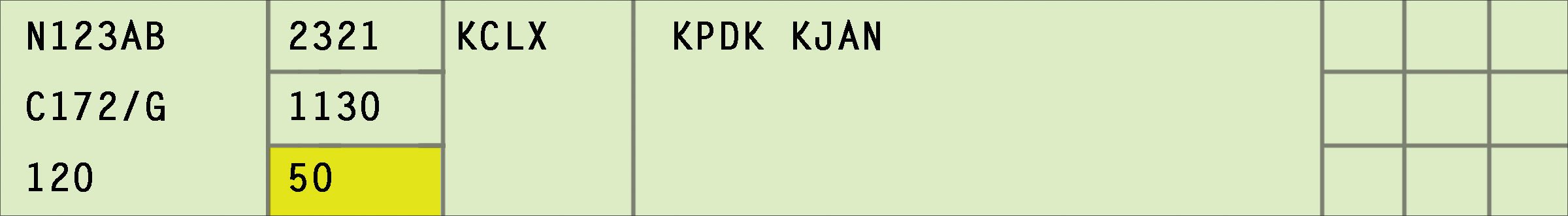

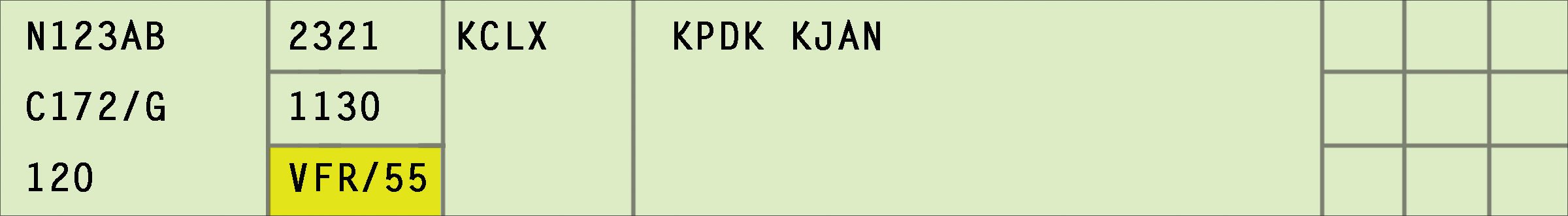

Say you’re flying N123AB at 5500 feet to an airport a couple of hundred miles away. Your flight progress strip shows “VFR/55” in its altitude box. Conditions are deteriorating, so you request an IFR clearance to continue at 7000.

No problem. ATC just amends your flight plan’s requested altitude in the computer. If you’re talking to Center, they can do it right at their scope. We approach control guys rely on a flight data controller to make those kind of alterations at a specialized computer station.

So, if I took your request, I’d turn around and yell across the room, “Flight Data, amend N123AB to 7000.” He might be busy with other amendments, disseminating weather, or with other duties, but soon he’ll change your altitude to “70” in his computer. An altitude without a “VFR/” prefix is automatically IFR. Meanwhile, I’ll issue your clearance with the 7000 as the final altitude and get you climbing. It’s not instant, but it gets done, and every facility can see you’re IFR now.

The pilot doing his BFR was right. He called the center and they confirmed it. Contrary to what his instructor thought, getting a pop-up IFR clearance isn’t a difficult undertaking—just ask. Chances are high you’ll get it, but they’re certain you won’t if you don’t ask.

Of course, how fast you get it is dependent on how busy the controller is at that particular moment. It may be minutes before your flight meets his separation requirements and he’s able to get you cleared, so plan ahead a bit before calling for a pop-up. Use good judgment, think ahead, say your intentions clearly, and give ATC some time to work you into the system.

Tarrance Kramer separates traffic—both VFR and IFR—at a TRACON in the southeast U.S. He welcomes pop-ups and handles ‘em all the time.

Controllers are constantly processing and evaluating information about each aircraft within their purview. IFR aircraft have far greater separation requirements and restrictions than VFR flights, so one of the first things a controller determines is whether the airplane is VFR or IFR.

How can they tell which is which on a scope filled with targets? It’s actually pretty simple, once you know the symbology.

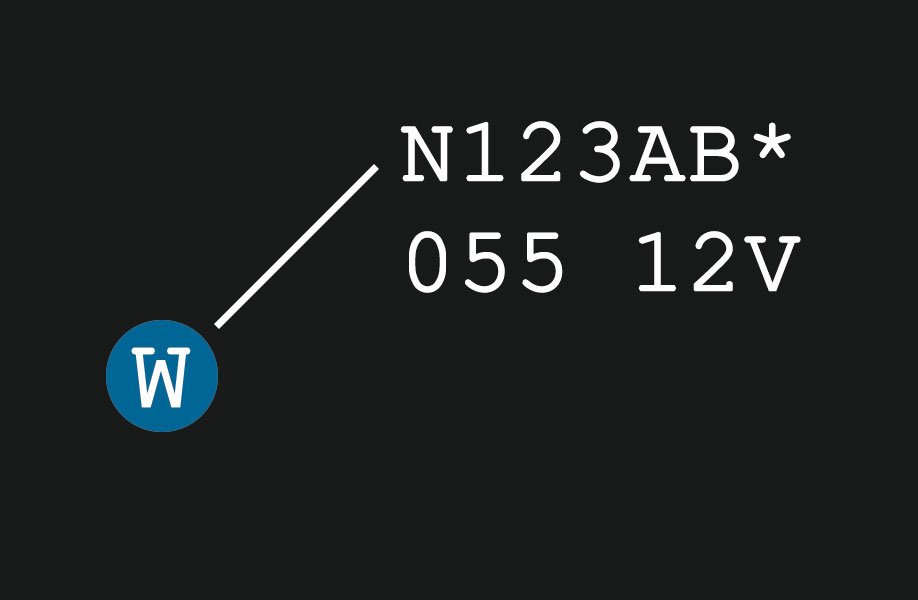

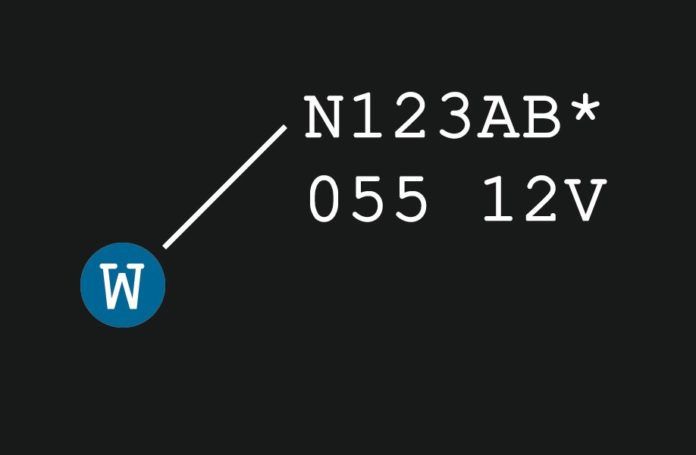

Both IFR and VFR targets display the same basic information—call sign, altitude and speed. However, a VFR target will have an asterisk appended to the call sign and a “V” to the right of the speed. The asterisk indicates that the Minimum Safe Altitude Warning system is turned off for that aircraft, so he can fly as low as he wants without triggering MSAW altitude alarms. The “V” is for “VFR,” of course. Aircraft without those symbols are assumed to be IFR.

For flight progress strips—the paper record each controller has about her traffic—the determining factor is equally simple. In the altitude block, highlighted here in yellow, VFR aircraft will have “VFR/”prefixed to the altitude. Aircraft without any altitude prefix are simply assumed to be IFR. —TK

Great and informative article. question, recently watched the Baron IFR denied on youtube. Was this controller correct? what is you take on this situation?

Would it be helpful to provide the IFR flight plan data to the controller when requested instead of “playing 20 questions” where the controller asks for data from each block of the flight plan?