Many of us just seem to need the latest gadgets. But others fly quite successfully with nothing on their laps but a chart and just conventional VOR navigation in the panel. Both ends of this technology spectrum are valid and which one is appropriate for you depends a lot on your type of flying, your skill and your level of comfort with the latest technology.

We recently ran a series of articles about datalink weather, comparing the primary data suppliers and the broad range of equipment, from expensive built-in equipment to the myriad portable solutions around $1000. However, those articles focused on providing information for pilots about to make product selections. Unfortunately, they bypassed the fundamental discussion of whether you’d want datalink capability or not.

So, if you haven’t made the jump to datalink information in your aircraft—or for the suite of toys you take into rentals—and if you aren’t certain you should, this article about the benefits of all that information is for you.

My Baptism

Paraphrasing Carole King, my aviation world moved under my feet on the evening of May 24, 2008. I’d been assigned to instruct Jason, a 16-year-old student, on a night IFR flight. Our destination was Orlando Executive Airport 130 miles north. There was hefty convective weather around Orlando, and this was to be my inaugural flight in a G1000-equipped aircraft. I’d watched G1000 videos and studied the manuals, but I hadn’t yet flown it.

One of aviation’s many maxims is that if any three things aren’t right, don’t go. I was being cautious since I had at least that many. “Mitigate, mitigate,” became my mantra for that evening’s flight.

Our flight school dispatcher assured me that Jason knew the G1000. I then formed a personal Plan B. With good weather on the first part of the route, if I didn’t like the way the weather (or Jason) was developing, I could turn back.

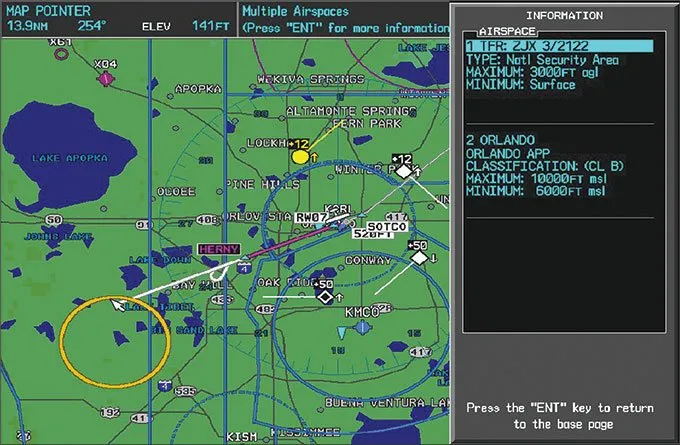

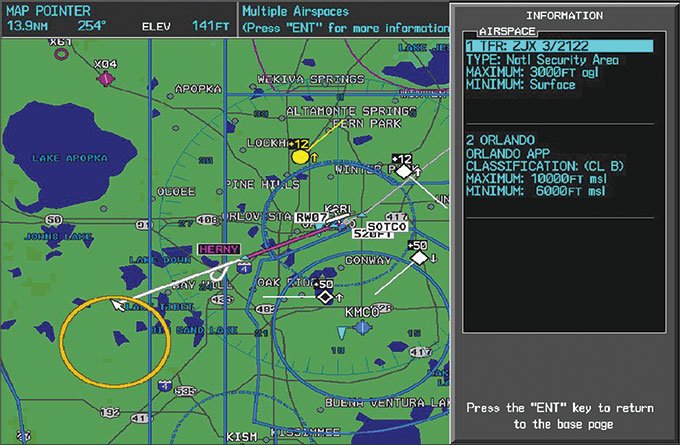

It turned out that Jason flew very well and ran around in the G1000 like it was his private playpen. What really blew me away, though, was the phenomenal situational awareness the G1000 gave us, showing us weather via XM satellite datalink, Mode-S datalink traffic, our location, airspace…everything. Jason flew a perfect ILS 7, and we were rewarded with a view of the spectacular nightly fireworks at Disneyworld, represented on the MFD by the amber TFR.

Departing was a bit more challenging. Mother Nature was making her own fireworks, with cells to our right snapping lightning like flashbulbs at a press conference. Yet NEXRAD showed that a straight-out departure would keep us clear, and the Stormscope confirmed it. The expert departure controller saw it, too. She sent us straight out and then vectored us around more weather until we escaped to the south with nary a bump—all while airliners were complaining about the ride.

Despite all the potential for trouble, I have never felt more comfortable in an airplane, in large measure because the NEXRAD datalink weather helped us avoid the rocks and shoals. This was IFR as I had always wanted it to be. I didn’t realize that at the time, but the manufacturers surely did.

There is a case to be made for flying a TSOed, built-in full system like

Garmin’s G1000 or Avidyne’s Entegra. There’s nothing on the yoke, no wires running everywhere. Both systems offer backup power one way or another. The permanently mounted antenna on top of the aircraft maximizes datalink reception from the satellite. And they use two datalinks: the satellite datalink and the Mode S (meaning datalink-capable) in the transponder to receive TIS data. More on that a bit later.

At the opposite extreme, some of our school airplanes have no datalink gear at all. Flying these airplanes, we look to forecasts for planning and to ATC for traffic and real-time weather. Having experienced the gamut of GPS maps, datalink weather and datalink traffic, lacking situational awareness avionics in these cockpits makes me feel like I’m flying with blinders on. Situational awareness (SA) goes way up when you can see your location, airspace, weather and traffic on a display right in front of you. Good SA makes sound risk management possible. As day follows night, more awareness begets better management.

Portables to the Rescue

After a few brave, false starts by aviation entrepreneurs over a decade ago, until the FAA recently launched FIS-B, the only portable option was to receive XMWX weather through a proprietary portable like those from Garmin, or a WxWorx data receiver feeding XM satellite weather to a laptop. (See Larry Anglisano’s “Cockpit Weather Choices” in February 2014.) The downside is that you need multiple pieces of hardware and a semi-pricey subscription; the upside is that you gain access to the richest set of weather products available.

Seeing a dual opportunity to undercut XMWX’s subscription cost and bring near-real-time weather, GPS location and traffic to airplanes without it, the ever-resourceful vendor community stepped up to offer us access to FAA’s free Flight Information Service-Broadcast or FIS-B. Today, a plethora of vendors support portable FIS-B in-flight weather systems, some even with TIS-B traffic. But note that not all software works with all hardware. Notably, the popular ForeFlight works only with a Stratus receiver; Garmin Pilot software pairs only with their GDL 39 receivers.

I have been flying the Garmin combination for about three months. It has been nearly as much of a revelation as my first experience with the G1000. I can put the GDL 39 in any airplane I fly. Garmin even offers a battery pack for aircraft without a power port. The receiver connects via Bluetooth to my iPad. If I forget my iPad, it works just fine with my iPhone under the same software subscription. I never thought that I would use my iPhone to navigate under a Class C shelf, but it works perfectly because the GDL 39 also includes a WAAS GPS receiver. I update charts on the iPhone just as I do with the iPad.

FIS-B has proved a tremendous asset. I can be out on a lesson and see any weather that might block our return to the airport. If there is weather, we simply request an approach well before we’ll get to the airport so ATC can plan for us.

FIS-B weather services work well and provide excellent airborne weather awareness. That said, you should be cautioned that it is no more intended to replace a certified preflight briefing than is XMWX. Garmin’s Pilot software can obtain an official DUAT(S) briefing, though, so if something happens, you will have a record of a certified briefing in your FAA dossier.

Tangentially, the maps, taxi diagrams and instrument approach plates are GPS-WAAS georeferenced. If a student turns the wrong way in a hold, I can show the error of his ways right on the plate. I have found many other ways to use the GPS functionality these devices offer, as I’m sure you will.

Portable datalink receivers pick up transmissions from ADS-B stations dotting the countryside. Since the one nearest us is 13 nm away, the link comes alive around 400 feet AGL after takeoff with the receiver and its integral stubby antenna mounted on the glareshield. However, you might need to be at least 1000 feet AGL within 37 nm of a station to receive it since transmission is line-of-sight. Unless you are parked near an ADS-B station, you must wait to see the weather until you’re airborne. This stands in sharp contrast to XMWX’s effectively omnipresent satellite signal.

Most stations are on or near airports. You can find station location and a lot of other useful information from the FAA’s website.

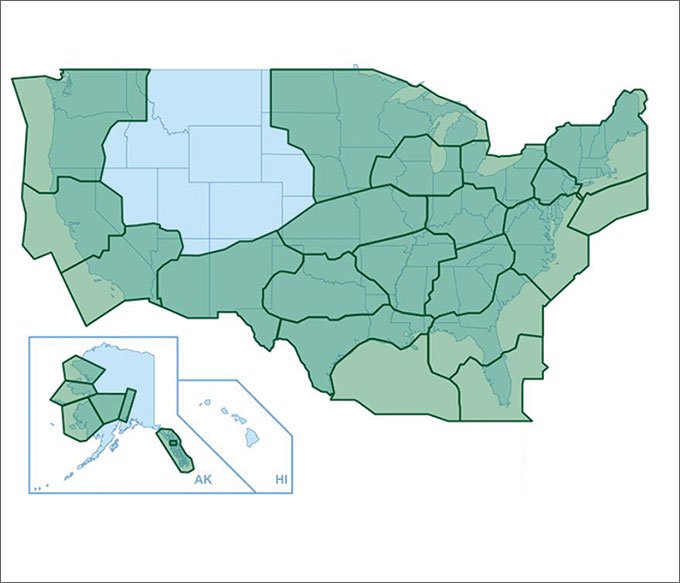

Prospective users in the northern mountainous west part of the country will notice a glaring gap in ADS-B coverage. This is because 133 stations remain to be installed this year with about 530 presently operational, making the network about 80% complete. Once the expected 663 stations are on-line the gap will be filled.

Traffic, Too

Airborne traffic surveillance is a bit more complex because ADS-B offers two Traffic Information System-Broadcast (TIS-B) datalinks in addition to the FAA’s TIS that’s been around for years. The UAT (Universal Access Transceiver) datalink operates at 978 MHz. It is primarily intended for GA operations below the flight levels. Only UAT also carries FIS-B weather, but FIS-B signals are good to Flight Level 240 and even FL400 with 90% coverage at a range of 150-200 nm from an ADS-B station.

At FL180 and above, the 1090ES datalink is recommended and will eventually be required. The 1090 frequency is used with Mode A, C and S transponders. ADS-B capability enlarges the transponder’s message set beyond the basic squawk code, altitude and (Mode S) unique identifier. These additional messages are known as “extended squitter” or ES. (Honestly, I don’t make this stuff up.)

Many portable devices will receive both UAT and 1090ES transmissions from other airborne equipment as intended by ADS-B. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the Garmin GDL 39 I used shows many aircraft operating with 1090ES transponders, some sporting airline flight numbers.

Although not portable, TIS is the original datalink traffic service. TIS is simply a broadcast of traffic seen by TRACON radar and about 107 TRACONs offer it. It has helped many pilots spot and avoid potential conflicts for years. All it requires in the airplane is a Mode S transponder and some type of display. For example, some of our flight school’s Cessnas have BendixKing displays coupled to BendixKing Mode S transponders. Coincidentally, I participated in the early design stages of Mode S in 1972, which got me interested in flying.

TIS is intended to help the pilot visually acquire nearby traffic in VMC. It is meant to improve on basic “see and avoid” by giving the pilot a clue where to look so potential conflicts can be resolved, but resolution of those conflicts is strictly up to the pilot. The AIM is most emphatic on this point: No recommended avoidance maneuvers are provided for, nor authorized, as a direct result of a TIS intruder display or TIS alert. In other words, TIS is not TCAS. TIS-B service carries the same admonition.

TIS draws on Mode A, C or S transponder traffic picked up by a terminal Mode S radar site. Typically every five seconds it then transmits that traffic information to your Mode S transponder, such as a Garmin GTX 330 or BendixKing KT73. The transponder sends it to your display—an MFD or even your navigator. Typical range for the datalink is 55 nm, line-of-sight. Don’t expect TIS service at low altitudes, especially in the mountains. Also, traffic below the floor of radar coverage will not show up on TIS. If the radar can’t see it, TIS can’t either.

This affordable first-generation traffic system is a gem. Installed in as many as 12,000 aircraft, TIS provides estimated position, altitude, altitude trend, and ground track information for up to eight aircraft within its service volume. TIS alerts the pilot to aircraft estimated to be within 34 seconds of a potential collision, regardless of distance or altitude. Further, a target reported at a distance of over seven nautical miles indicates that it will also be a threat within 34 seconds, but displays no exact distance. FAA considers TIS a nonessential, supplemental information service and as such is not covered by the NOTAM system.

Deployed only on terminal ASR-7, ASR-8 and ASR-9 radars, the future of TIS is downhill since the ASR-11 replacement for these older radars lacks TIS capability. This is probably because TIS is becoming redundant as it is replaced by TIS-Broadcast (TIS-B).

Parting Thoughts

I found that a yoke-mounted, full-sized iPad is too big. Many users suggest the iPad Mini is an ideal size, particularly for yoke mounting, and I agree.

Secure your equipment. One of my students did an overenthusiastic stall recovery that pushed us through zero-g. Suddenly the GDL 39 receiver was floating before me. I had previously stowed my tablet—if I hadn’t it might have risen up to smite me in the noggin.

Do you need datalink services? No, especially if you’re a fair-weather flyer. But the situational awareness and extra comfort of flight they offer are a modest-cost godsend to increase the utility and safety of serious instrument flight.

Fred Simonds tries to keep his eyes outside despite the lure of his gadgets inside. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.