If you’ve ever faced a go/no-go decision with tantalizing blue sky above a low layer of fog, you know that departing IFR is an option—with a few “ifs.” If the obstacle-departure procedures are okay; if conditions meet personal minimums and comfort, and if you’ve considered what you might have overlooked when in a hurry to get in the air.

Dawn Patrol

The plan was solid: Leave early from LaTrobe, Pennsylvania (KLBE) to beat the fog and enjoy sunup before a long day of meetings in Philly. After preflighting you push your Skylane into the morning twilight. The forecast called for patchy fog before sunrise at 0630, and you’re 20 minutes ahead of it. But a rough magneto led to a prolonged runup to clear the engine and the suspected plug fouling. By the time all was running smoothly, sunlight has peeked above the horizon and patches of fog begin appearing.

The first inclination is to wait for it to burn off enough for a visual departure. But another option is to depart on instruments, get above the fog and into the clear. It wouldn’t be a Part 91-legal-but-scary zero/zero departure. Over the departure end of Runway 6, it looks closer to ¾ mile, or about half the 8200-foot runway. And the fog is broken in the surrounding area; probably no more than 200-300 feet thick. Not too bad, right? The AWOS is similar: wind is northeast at five knots, visibility one-half mile. But there’s also a readout of “vertical visibility 100” with temperature/dew point the same.

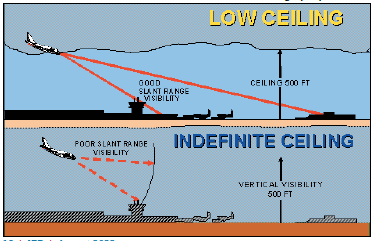

Vertical visibility is defined in Advisory Circular 00-45H, Aviation Weather Services: “If the sky is totally obscured with ground-based clouds, the vertical visibility is the ceiling.” Ceiling of 100 feet? Ouch. VV is also associated with indefinite ceiling, which obscures visibility both laterally and vertically in what the AC illustrates as “slant range visibility,” which would be the worst for inbound aircraft. It would also indicate that on climbout, with a nose-up attitude aimed at the fog layer, you’d have, in effect, zero visibility, regardless of what the AWOS, behind you and pointing straight up, happens to broadcast.

Options, With Caution

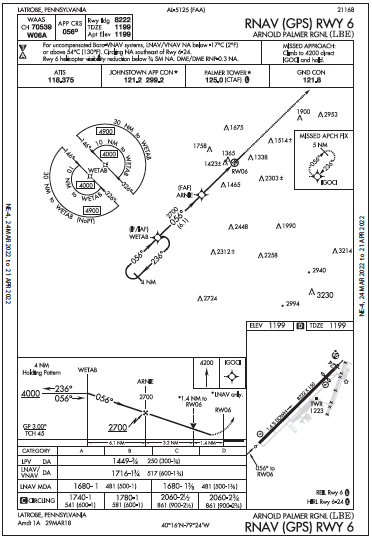

Even so, when departing IFR under Part 91, there’s lots of flexibility, with the tradeoff of more risk. There are no minimums to depart. IAPs back into KLBE include RNAV 6 with LPV minima of 1449-¾, or 250 feet AGL. The ILS 24, goes lower to 1345-½, (200 feet above airport elevation). But unless you accept a small tailwind on 24 (okay on this long runway), circling minimums are 2380- 1-¼ , or 1181 feet AGL, for Category A. What’re the odds of having to fly an approach back in? Even if the AWOS gave you a number for legal minimums under §91.175, slant-range visibility could mean a zero-vis approach.

Think back to the takeoff reg, for which Part 121 and 135 operations must use a takeoff obstacle clearance or avoidance procedure when IFR. So when there’s a standard minimum listed that refers to the visibility requirements: one statute mile with two engines or less or ½ SM with more than two engines.

For KLBE Runway 6, takeoff minimums are “std. w/min. climb of 220 feet per NM to 3300 or 1700-3 for VCOA.” The ODP instructs a climbout on “heading 041° to 3300 before proceeding on course.” There’s no mandate for you to use these, but they’re there for a reason.

While your nimble single-engine aircraft needs less room for takeoff and climb, you simply can’t see what’s in front. Even if some of the criteria don’t legally apply, AIM 5-2-9 does point out in item c: “Pilots operating under 14 CFR Part 91 are strongly encouraged to file and fly a DP at night, during marginal Visual Meteorological Conditions and Instrument Meteorological Conditions, when one is available.” You’ve got some of that covered with a simple ODP, so it’s just a matter of deciding what to do about the foggy departure.

On taxi, you monitor AWOS and consider: Will you go when it gets back up to ILS minimums of 200-½? You’ve departed in similar conditions with the flight director on a seven-degree climb attitude, maintaining runway heading with the bug while checking the engine instruments. That bug will need to move to 041 degrees after takeoff. Meanwhile, the end of the runway probably won’t be in sight for the takeoff roll, as you’ll need less than 1000 feet to rotate.

While pondering this, Tower opens, so you request a back-taxi down the runway to check things out and return to 6. It’s quiet and you’ve got at least a few minutes to kill here on the ground. You’ve accomplished two things with this: Checked the runway for debris or other hazard, and confirmed that the visibility is indeed a half mile on both ends. You don’t want to get caught off guard in actual zero-zero while accelerating. Worse, disorientation with a sudden change in the windshield during acceleration/rotation would increase the risk, so having a glimpse of pavement ahead and below will help your inner ear agree with the instruments.

The Lineup

So far it’s okay, but you’ll need another few seconds to brief: Select a point on the runway that allows for an aborted takeoff and stop. That’ll be halfway down, abeam the buildings. If engine roughness returns, or a gauge is off, or airspeed lags by then, bring power to idle, brake as necessary while tracking straight ahead, and call it a day. (While many of us flying Part 91 didn’t learn to use these takeoff briefings for single-engine aircraft, they’re starting to appear, and for good reason.)

As for the what-if of engine failure, the standard drill, while far from ideal, is all you’ve got: Assess the close-in obstacles before you go, since you won’t be able to see ‘em. Land straight ahead or slightly left or right if need be. If still generating power when above an altitude feasible for the approach, have them ready; the ILS might be the nearest inbound.

If you’re above 4000 feet, that’s the Terminal Arrival Area around the airport. Your EFB and ATC can also assist with obstacle avoidance. If you’re on course and there’s an emergency, Johnstown is 27 miles east and has better weather at 300-1—just good enough for an LPV 5 or 33, or ILS 33 approach.

After a couple more minutes planning, you see the pile that built up trying to make this work. As if on cue, Tower chimes in to see how you’re doing. Um, how about a runway taxi to re-exit at F, where you’d like to shut down for a few minutes to monitor the visibility; a mile would be nice. And by the way, could you confirm with Departure we want the ODP?

The fog starts to break up 10 minutes later, and you hear twins lining up on approach as you return to the hold-short line. After the first one touches down, you’re given “Cleared for takeoff, no delay.” Wow, that pre-brief really is handy as there’s no time now to hesitate. Already on instruments as the nosewheel lifts off, you stay on instruments and by the time you reach the new heading at 1900 feet, the fog’s already well below and behind.

You spent a lot of time to manage that critical few seconds on departure, and now you’re ten minutes late. But the stress level, instead of prompting a rushed departure into the fog, perhaps encouraged waiting. The delay was, in the end, well spent forming a takeoff briefing that’ll save precious minutes in future departures, regardless of the weather.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where she serves as a FAASTeam Lead Safety Representative to promote takeoff briefings and other tools from the pros for Part 91 single-engine pilots.