Let’s introduce you to Fred. He is a fictional pilot. Some say he is just “Fred”; others say he is a “Flight-Related Experimental Demonstrator” for Wx Smarts. Either way, he’ll help us experience flying through a real winter weather system across the southern U.S., guided by a veteran aviation weather forecaster. (That’d be me.)

Fred will fly his Baron 58 from Memphis Olive Branch (KOLV) Airport to Odessa (KODO) in West Texas to monitor some new oil leases on his family’s ranchland. A neighbor thinks the oilfield company was setting up on a field with no lease. Fred hopes to be done early so he can make it to the local BBQ place in Midland for brisket, then he’ll fly back to Memphis.

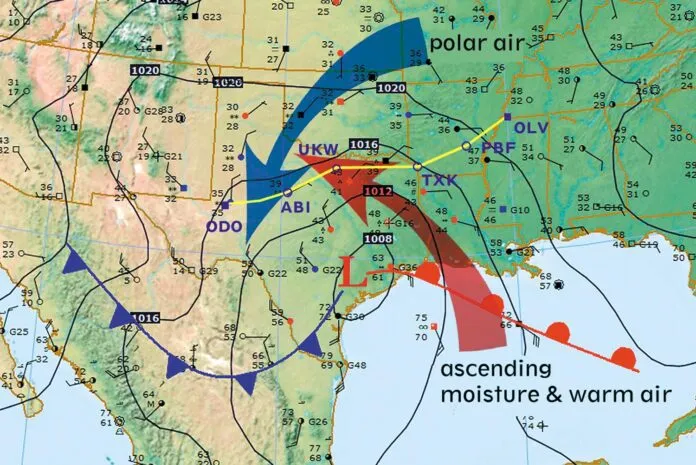

Unfortunately, there’s unsettled weather ahead. It’s January 24, and that brings the distinct possibility of icing and winter weather. The surface chart shows a developing low along the Gulf Coast near Victoria. Winds are blowing cyclonically into this low-pressure area, with northerly wind across much of the region. It’s snowing from Oklahoma City to Amarillo, and across much of West Texas. A polar front stretches through the frontal low, extending from Houston into northern Mexico.

Planning the Flight

Fred checks the TAF for Midland: 36011KT 3SM -RA BR OVC003 with a temporary group of one mile in light snow for the next three hours. Later in the afternoon the ceilings lift to 1500 feet with a slight increase in the winds. Not great, but in Fred’s opinion the flight is just typical January weather.

Fred is a bit rushed and doesn’t call for a briefing—it’s a daytime flight he’s done many times before, his plane is certified for icing, and he’ll land early if it gets too bad. He also plans to monitor SIGMETs along the way.

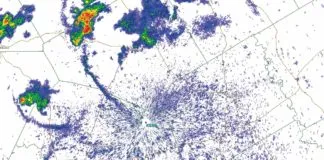

He logs into Aviation Weather Center and checks the METARs along the way. Memphis is VFR—no problems there—then MVFR ceilings and precip picks up around Texarkana. The DFW area has moderate to heavy rain with temps in the 40s, and MVFR to IFR ceilings with three to four mile visibility that drops as low as one mile in snow between Abilene and Midland.

With 44 degrees at Dallas, there’s freezing weather a few thousand feet above the surface. He uses an old rule of thumb that with temperature falling at 3.5 degrees F per thousand feet the worst of the icing will be just above 4000 feet. This is not entirely correct as we’ll see. Adding more confusion, the Aviation Weather Center SIGWX chart shows a freezing level of 4000 feet, convincing Fred that the icing problems will be between 4000 and 10,000 feet.

He files IFR for 14,000 feet figuring he’ll be on top of everything. He takes a quick look at the radar. There’s lots of precipitation along the way, but again it’s nothing he hasn’t handled before. The Baron handles ice pretty well, and his de-icing equipment will keep him out of trouble.

Go West, Young Man

Fred takes off around 1620Z, heading southwest toward the Mississippi River, and V16 all the way to Midland-Odessa. The weather is about as expected, and he soon enters an area of overcast. The OAT is a little warmer than expected—around -10 degrees C—but he figures it will drop as he approaches the colder air in Texas. Instead, it rises.

Around Pine Bluff, south of Little Rock, he enters a mix of rain, graupel, and snow. Fred activates the boots and prop deice, and turns on pitot heat. Over the next 10 minutes the ice gets heavier and begins coating windshields, wings, and other exposed surfaces.

Shortly after switching over to Fort Worth Center, the OAT continues to rise and is now -5 degrees C. He’s over southwest Arkansas, in heavy icing. Even with the de-icing equipment he’s had to gradually bring up engine power and is getting nervous.

“Fort Worth Center, November 65 Alpha. I’m picking up ice at 14,000. Any other reports?”

“November 65. Say flight conditions?”

“Uh, Fort Worth Center I’m in heavy precipitation, I’m gonna call this severe, and the controls are getting a little heavy.”

“November 65 Alpha, we’ve got multiple reports of light-to-moderate icing from 5000 up to 20,000. A CRJ out of Fort Smith reported moderate ice at 8000, and a Citation out of Texarkana reported moderate ice at 5000 to 12,000. Advise if you need a different altitude.”

Fearing a runaway icing problem and no relief at higher altitudes, Fred decides to drop down into the warm air. “I need lower. Requesting 4000.”

“November 65 Alpha, at your discretion descend and maintain 4000.”

“Roger 4000. November 65 Alpha.”

Breaking It Down

The weather was marked by easterly and southerly flow across East Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana from the developing low along the Texas coast. This corresponds to a warm conveyor belt (WCB), marked as a red arrow in chart on the facing page. In spring and autumn, it is often co-located with the low-level jet and severe weather.

We also find a cold conveyor belt (CCB), marked as a blue arrow on the chart. These are involved in many cold-season weather systems in the U.S., with the juxtaposition of these two features marking some of the worst weather. The CCB also produces the “comma head” often seen on satellite photos, and is associated with the deformation zone northwest of deep surface lows, where overcast weather, IMC, and reduced visibilities are common.

The WCB and CCB arrows aren’t narrow corridors but indicate a broad region of warm and cold air. For example, the cold air flowing southwest stretches from Dallas to Amarillo. This CCB is close to the surface up to 5000 feet, and is best seen on surface charts.

Meanwhile the WCB is warm, moist buoyant air. South of the cold front and warm front—the warm air mass source region—it exists through a deep layer all the way to sea level. But as it gets drawn north over the warm front, it rises. The exact height depends on the slope of the warm front, but it is commonly found at 5000 to 15,000 feet a few hundred miles north of the warm front.

The WCB represents a tongue of elevated warm air wrapping around the north side of the low-pressure area. Near the CCB, the warm air contrasts with the cold surface air and the cold upper tropospheric air well above.

Help From Soundings

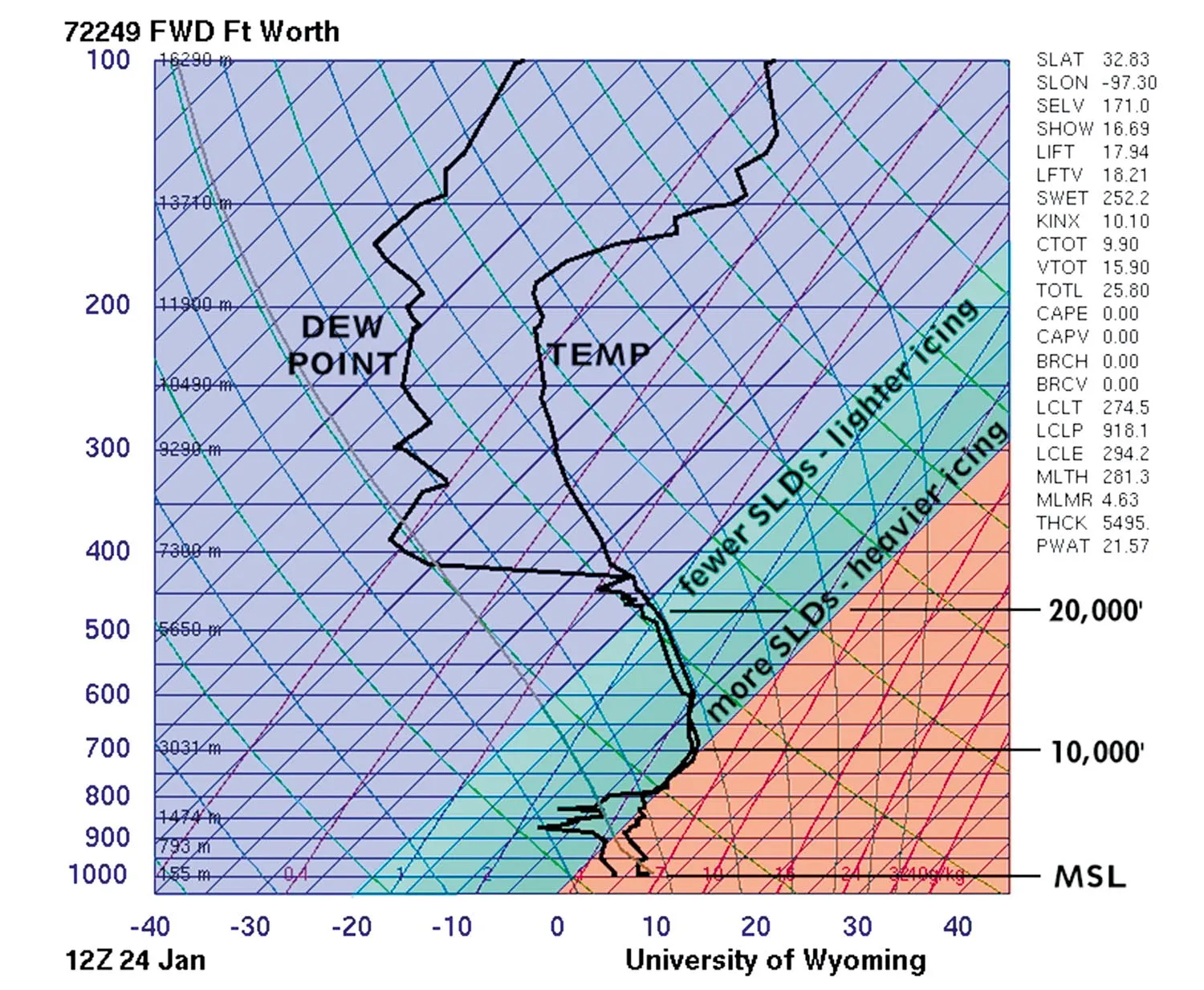

Soundings, though they are a bit technical, show the distribution of air masses. You can learn more about them in the January 2022 IFR. The Fort Worth sounding below shows how the cold polar air from the CCB, is rooted in the low levels. It’s marked by steep lapse rates from the surface up to 5000 feet. The separation between the temperature and dew point line shows lower relative humidities, and since this is the driest part of the sounding below 20,000 feet, suggests the air mass near the ground is of northern origin.

Above 5000 feet there’s an inversion that moves up into the tropical air mass associated with the WCB. Temperatures become isothermal or even rise, reaching a peak of +1 degree C at about 9000 feet. But much of this layer is subfreezing, hinting at serious icing problems and the potential for large supercooled drops. The worst problems are in the dark cyan shading where layer temperatures range from -5 to 0 degrees C.

Above 15,000 feet we transition out of the WCB layer and back into typical upper-tropospheric air, marked by a return to steep lapse rates and rapid cooling with height. As a bonus, I’ll point out the tropopause shown on the sounding at the 180 mb level, or about 40,000 feet. We see a sharp inversion above, with temperatures increasing by 10 degrees. That’s the stratosphere.

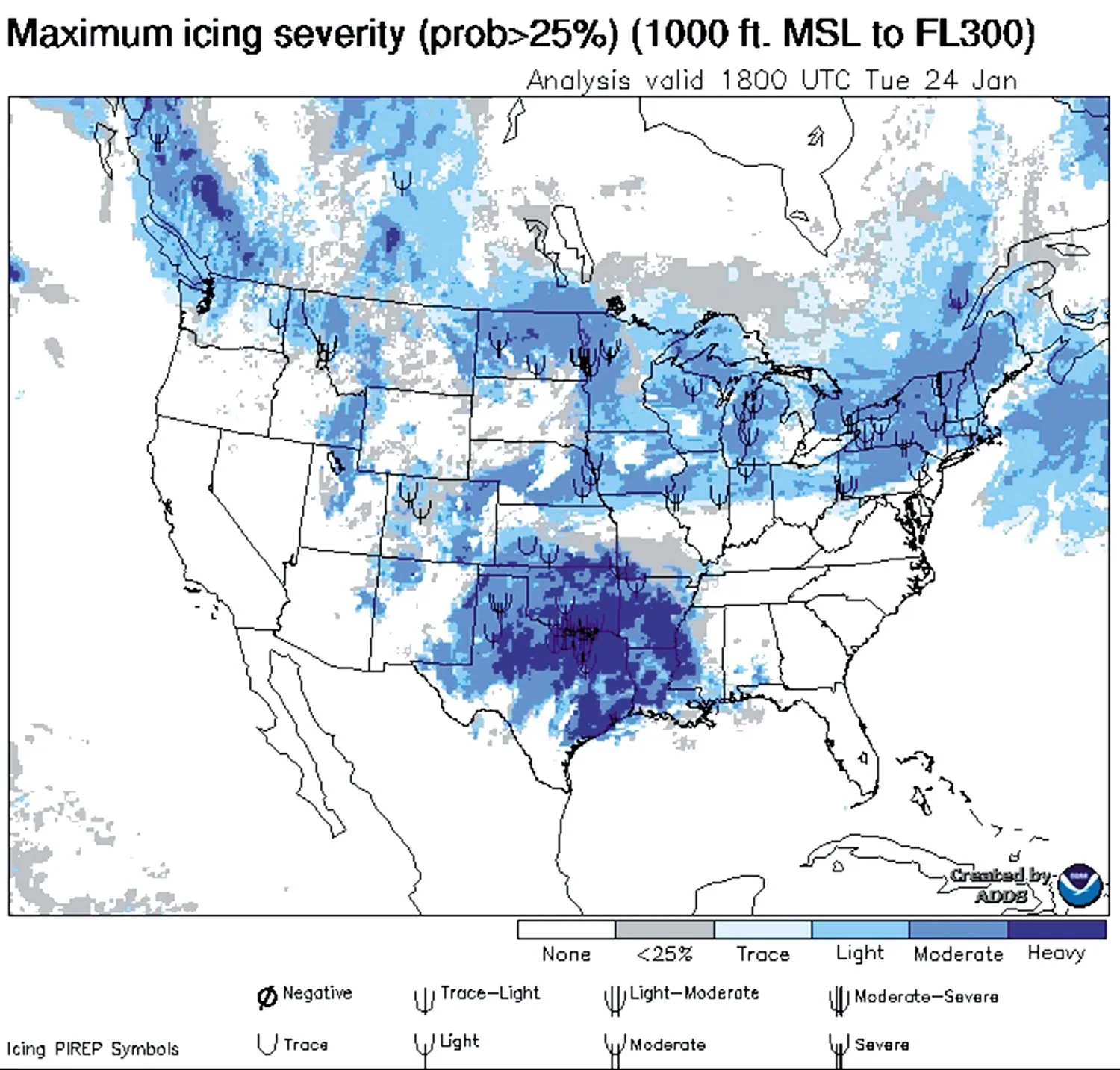

Overall, this sounding illustrates some of the icing problems that were most heavily concentrated between 5000 and 10,000 feet. The Aviation Weather Center forecast graphics showed that the icing conditions were extensive and most heavily focused around the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where moderate icing was likely.

This also shows that the stated freezing level is rather limited in what information it provides. It does not provide any information on the complex thermal structures in the vertical, in particular the presence of the WCB. In fact, the Fort Worth sounding shows two freezing levels: one at 6000 and the other at 10,000 feet, with the important icing band (0 to -10 degrees C) lying between 10,000 and 16,000 feet.

We also must consider changes over time and space. The Fort Worth sounding is a snapshot at 1200Z, about four hours before Fred’s flight. Though we don’t have any information on how the WCB is changing with respect to time, common sense tells us that the atmosphere warms as we go southeast, into the WCB, and cools as we go northwest, into the CCB and thermal trough.

As a forecaster, I can pick up the Fort Worth sounding, mentally shift the temperature traces to the left, and estimate that significant icing layers in western Oklahoma will likely span 4000 to 12,000 feet. And to the southeast, at places like Lufkin and Shreveport, the icing will be between 8000 and 18,000 feet, depending on how much I want to shift the line.

Deadly Precipitation Types

It is somewhat fortunate for Fred that there was plenty of warm air wrapped up into the system, with surface temperatures in the 40s. Quite often conditions are much colder near the ground. When there is an active WCB containing temperatures above freezing, with subfreezing temperatures at the ground, this is the classic setup for sleet (ice pellets) and freezing rain. Both of these are associated with severe clear icing, since they involve large drops falling into subfreezing layers.

Even though sleet does not pose much risk by itself to aircraft since the drops are solid ice, this type of precipitation is caused by liquid drops falling into a subfreezing layer, and this implies that somewhere up above, supercooled water droplets, originating from either rain or melted snow, were on their way down through a subfreezing layer. That layer is where severe clear ice exists. In most situations this layer is a few hundred to a few thousand feet AGL.

As you can see, the situations can rapidly get more complex, and lateral changes in the route can even bring you into entirely different weather regimes and processes I haven’t described here. Hopefully the information I’ve covered gives you a better sense of how to get a feel for conditions given a few common types of weather charts found on the Internet. I still encourage you to get that weather briefing before departing to keep things legal and make sure you’re getting the best information available.

Checking on Fred

Fortunately the weather shook some sense into Fred, and he decided better planning was called for. Even though he was VFR under the overcast, he landed at Texarkana Airport, and decided to talk to a briefer this time. His new plan was to grab some lunch and wait a few hours for the weather system to continue moving northeast, as the TAFs were showing an improving trend and the briefer expected icing to diminish.

Fred opted for a more southwesterly route via Austin, with warmer temps, and he was able to get into Odessa later that evening. And, being the generous storyteller that I am, he got that BBQ he wanted thanks to a catered event taking place at Odessa Airport’s FBO.