There’s an ancient quote that says “wise men learn from their mistakes, but wiser men learn from the mistakes of others.” There is probably no industry or profession where this is more true than in American aviation.

Pilots get a pass for confessing to the Aviation Safety Reporting System, while the private sector (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University), not the U.S. government, maintains one of the largest online repositories of NTSB accident documents. There’s no shortage of lessons to be learned and a great culture of diffusing this hard-won wisdom.

So, let’s delve into a few randomly selected NTSB accident reports, supplemented by any available press stories. These have been paired with weather archives. There was no attempt here to cherry-pick noteworthy accidents and make them fit a particular narrative. Rather, I started with random flights where enough data was available, and from there tried to understand what went wrong. These are the stories that fate dealt me as I wrote this article, with suggestions on how we might be able to do better.

Don’t Mess With Texas Storms

Late in the morning of November 8, 2009, a Beech A36 Bonanza took off from Kerrville, Texas, located about 50 miles northwest of San Antonio. The pilot was single-engine rated with almost 1000 hours of flying time, but only 4 hours in this aircraft type. He filed an IFR flight plan for 9000 feet with a destination of Houston, about 200 miles to the east. The only thing that stood in the way was a cluster of garden-variety thunderstorms over the San Antonio area, the type that give seasoned pilots little thought and are just an annoyance for forecasters.

To underscore that point, the Storm Prediction Center had no watches in effect and simply placed the area under a small outlook for “general” thunderstorms, not severe or even enhanced. At 10:04 AM 21-year veteran forecaster John Hart noted that a shortwave was producing “scattered showers and thunderstorms over South Texas, and weak lapse rates and minimal vertical shear will preclude organized severe storms.” Freezing levels were reported to be 12,000 feet near Del Rio and the airplane would remain well below this level.

The pilot obtained a weather briefing at 9:20 AM, and was given an AIRMET for IFR and icing above 13,000 feet. The briefer looked at the TAFs and told him that Houston would expect storms later in the day. The pilot told the briefer that’s exactly why he was trying to get there and back.

The Bonanza lifted off at 11:10 AM, with the 60-year old pilot and his two grandsons, aged 13 and 12. The plane climbed through shallow stratus overcast and broke out into VMC above. A large mushy anvil covered much of the sky, well above 20,000 feet, and the airplane turned eastward, climbing to its cruise level. From this angle the thunderstorm area would have appeared like a diffuse and featureless gray mass spanning the horizon from northeast to southeast.

The airplane entered the thunderstorm area, and there was no discussion with ATC about the weather until the time of the accident, when Houston Center asked if the plane was turning south because of weather. There was no response. The aircraft responded to a transponder IDENT request, but quickly disappeared from radar. The wreckage was found later in the day in a cattle pasture north of San Antonio. All three on the aircraft died.

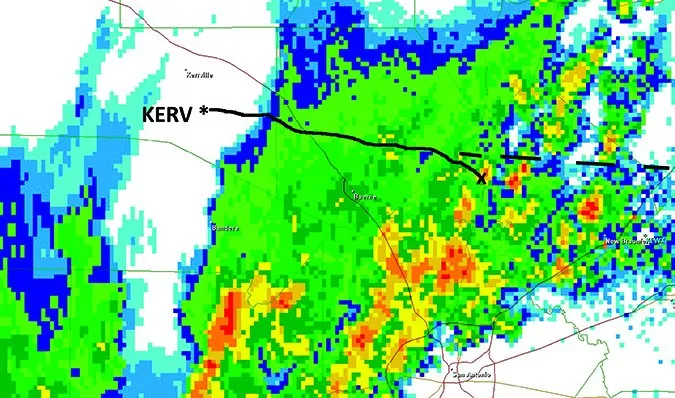

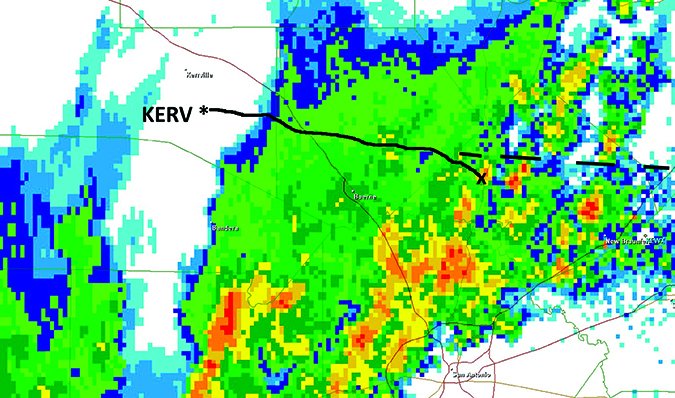

Radar images quickly showed what happened: the aircraft flew directly into a developing thunderstorm cell. From my experience as a forecaster, nothing about this cell looked particularly strong. It topped at 20,000 feet and instead of looking severe it had a “rainy look,” typical of the late-fall subtropical storms that occasionally affect south Texas. However the airplane managed to fly directly into the center of this 4-mile wide cell.

I’m continuously surprised that even the weakest of storms can cause problems, including this one. While there is no such thing as a safe thunderstorm, I would say a skilled instrument pilot with the right tools would have been able to navigate this particular cell without incident. No one—not even the investigators—know what went wrong. One might speculate that the pilot’s skills were rusty or he wasn’t sufficiently familiar with the type and equipment, or even that there was an undiscovered mechanical problem. But we do know that a weak cell was singularly responsible for the downing of this plane, randomly plucked out of the NTSB records.

Get-There-Itis

Our next accident also began with an early morning storm—this time in VMC and six miles from the nearest precipitation. This pilot had stronger credentials: 2000 hours total time with solid instrument skills. Friends said he was a meticulous and cautious pilot not known to take any risks when it came to flying in inclement weather.

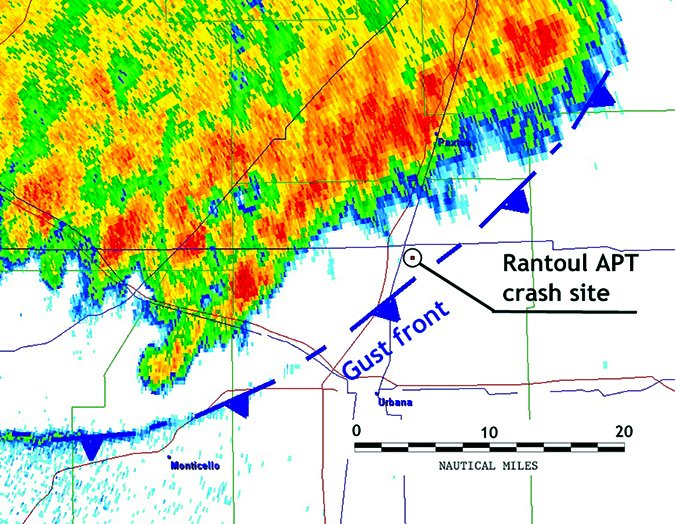

On July 24, 2011 this pilot and two passengers loaded up a Piper PA-46 Malibu from the Rantoul Aviation Center in Illinois, formerly Chanute AFB. A line of thunderstorms stretched from the west through the north, but good conditions prevailed at the airfield. A witness said the pilot performed his preflight inspection of the airplane in a hangar. Meanwhile, the pilot’s wife said she had to use the restroom. The pilot said to “hurry, because a storm front is coming.” A broad dark shelf cloud filled the Rantoul skies, bearing down on the airfield.

Rantoul started out with light southwest winds, but at 9:15 AM as the airplane began its taxi, the automated ASOS site issued a SPECI observation with winds out of 300 degrees true at 14 gusting to 21 knots. By this time, the shelf cloud had passed overhead, but no rain was occurring and conditions stayed VFR.

The airplane took off five minutes later on Runway 27 into a brisk outflow wind. Witnesses said the airplane reached 500 feet and had its landing gear up. Then it looked as if something pushed the tail up and the nose down. The airplane dived and impacted the ground, with the engine running all the way to the point of impact.

So what happened? The radar image for the time of the accident showed a mesoscale convective system northwest of the airport. However the nearest rain was five miles away, and the nearest heavy rain was eight miles distant. A gust front was distinctly visible on animations (see illustration for the estimated location) and it could be easily traced on spectrum-width images. The airplane was sandwiched between this gust front and the thunderstorm area.

Once again, the “thunderstorms within 20 miles rule” applies. Even more so is the rule “don’t take off or land in the face of approaching thunderstorms. A sudden gust front of low-level turbulence could cause loss of control.” In this case, it’s possible that the aircraft punched out on top of the outflow and encountered a sudden tailwind of strong low-level inflow, and this was likely enough to almost immediately stall the plane.

I’ll add here that meteorologically we often see all sorts of microscale circulations along outflow boundaries, like vertical vorticity centers that further concentrate the winds and cause strong shear patterns. These often are “stretched” by updrafts, forming the landspouts we sometimes see around airports like Denver International and those on the Florida coast. They don’t form due to deep storm-scale mesocyclones, but instead from the extension of compact, intense circulations into larger circulations creating visible cloud features such as these.

You normally don’t see these on NEXRAD and TV radars because it takes research-grade radar to sample them in depth. Academic-government partnerships like NCAR and NSSL have been at the forefront in exploring this type of technology. Once you’ve seen some of the data that comes out of these field studies, you really get an appreciation for the fine-grained, intense circulations that are possible around outflow boundaries, gust fronts, and microbursts. I can assure you the wind field is even a little scarier than you might think.

Forecasts are just barely coming to grips with one form of them: the type of tornado that develops along the leading edge of severe derecho windstorms. These are still very difficult to predict and it may take the next generation of phased-array weather radars to get a handle on them. The takeaway from this is to respect the 20-mile rule, and if you can’t do this, try to make a commitment to widening your comfort zone when around storms and trusting your gut instinct.

When Luck Ran Out

That leads us to the curious case of our next pilot, who departed Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on September 2, 2013 with his wife on board. Both were pilots known for their love of aviation, and together they flew the exotic Cessna T-50 Bamboo Bomber they brought to airshows around the country. In this case, the pilot flying was a veteran with a whopping 18,300 hours under his belt and multiple ratings. His wife had almost a thousand hours of single-engine operations in her logbook.

On this evening the plane was bound for a private grass field in the Scranton area. The pilot obtained his weather briefing while in Ohio, some hours before arriving at their departure point. A SIGMET was in effect and a severe storm watch had been issued from 3:20 PM until 10:00 PM Eastern time covering all of northern Pennsylvania. The briefer cautioned the pilot about IFR ceilings and recommended against VFR flight into Pennsylvania. The pilot replied, “Roger, understand. We’ll look at weather radar. Thank you much.”

This flight was conducted under VFR and no flight plan was filed. The pilot made a refueling stop and departed Lock Haven at 7:37 PM to conduct the final 85-mile segment. There was no further communication with the aircraft until an eyewitness near the airfield reported seeing a plane while taking a walk with his dogs. He said it “sounded like a WWII plane” as it flew west-to-east, then it returned the other way right on top of the trees. It flew into the direction of an “enormous black cloud with lightning flashing out of it” and eventually out of his view.

Nothing more was heard of the airplane. When a family friend reported to the state police that it hadn’t arrived, an ALNOT was issued. State police and Civil Air Patrol found the wreckage in a remote field a week later and confirmed the two fatalities.

What exactly happened to get such an experienced crew in this predicament? First of all, we know it was nighttime. The sun angle was at -10.8 degrees, placing it just past civil twilight. We also know this was not a collision with a hilltop, as the airfield lies at 1600 feet MSL and the accident site was an open field at 1400 ft. And in this forecaster’s opinion it’s unlikely there were more than a few scud clouds on this side of the storm and they would have been illuminated by lightning.

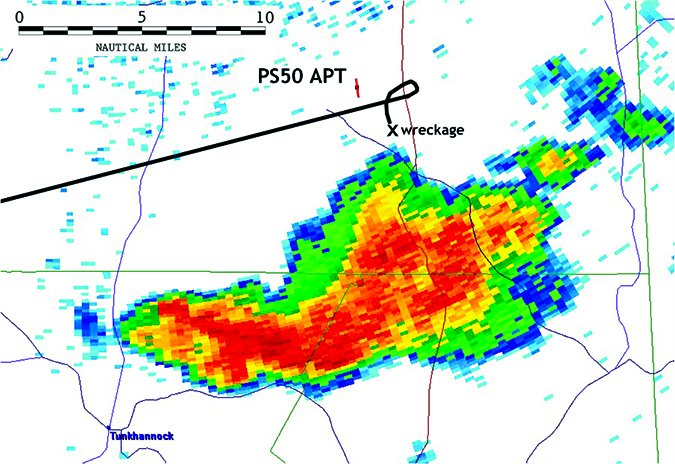

High-resolution Level II NEXRAD radar archives from Binghamton (pictured) provide a crystal-clear look at the weather at the destination. A strong thunderstorm was in progress just to the south, topping out at 41,000 feet. The wreckage was two nautical miles from the edge of this storm, so to this experienced forecaster it’s clear the airplane did not enter the thunderstorm itself.

However, the airplane was in close proximity to a gust front and outflow winds driven by 51 dBZ echoes to the south. These echoes were moving rapidly east-northeast at 35 knots. Evidence of this outflow bubble was apparent on spectrum-width imagery, and a layer of elevated 30 dBZ echoes at 20,000 feet embedded in the anvil overlaid the accident site, hinting at fresh downdrafts on their way downward.

The limited picture we have of the airplane path suggests it was trying to maneuver to turn on base for an approach to Runway 36 without entering the storm itself. This paints a picture almost entirely of unexpected wind shear problems, a possible turning flight stall, and the plane boxed in on the approach by storms with no altitude or airspeed to spare.

Once again, we return to the “avoid thunderstorms by 20 nautical miles” rule.

I won’t expound further on any of these tragic accidents, but leave it to the charts we’ve presented and to the stories told here to bear it out. And I would suggest reviewing the AIM, section 7-1-28 on Thunderstorm Flying. Those guidelines are well founded. Stay safe out there.

Tim Vasquez is a professional meteorologist living in Palestine, Texas. See his web page at www.weathergraphics.com.