The overcast was holding steady at 900 feet. Morning visibility wasn’t faring much better, showing two miles. The airport was IFR and the beacon was lit. The temperature and dew point were dancing in lock-step.

I was working Ground and Clearance. A deep voice rumbled through my headset. “Clearance, N4173A, requesting Special VFR. I’m just trying to jump back over to Hewitt under that cloud deck. I’m a Cessna 172 and I got information Mike.”

I recognized the call sign. He was a local pilot based at a private nontowered airport just ten miles to the west. He had flown in here yesterday, when it was nice VFR.

A glance at our tower radar display showed a stream of jets being vectored for ILS approaches. “N4173A,” I replied, “expect at least a ten minute delay due to inbound IFR traffic.”

A pause. “We got time,” he said. I acknowledged him and typed his flight info into our computer.

Unfortunately, neither N4173A nor I knew that the delay was going to be longer than ten minutes. You see, Special VFR involves a unique set of rules and headaches. Working around them requires some patience and hard decisions from both the pilot and ATC.

Regulatory Refresh

Are you a bit hazy on Special VFR specifics? In short, it’s a set of rules allowing a VFR airplane to fly in or through an airport terminal area where the weather is below normal VFR standards. It doesn’t require an instrument rating (during the day) or special training. It’s designed to get you in or out without complex instrument procedures.

Just for comparison’s sake, let’s briefly revisit private pilot ground school. In Class B, C, and D terminal airspace, flight visibility must be at least three miles to maintain VFR. Class C and D cloud clearance requirements are 500 feet below, 1000 feet above, and 2000 feet laterally from clouds, whereas Class B just needs you to remain clear of clouds. There are other modifiers for altitudes above 10,000 MSL.

Special VFR weather minimums for fixed wing aircraft are reduced to a mere one mile of flight visibility and the straightforward requirement to remain clear of clouds when operating within Class B, C, or D surface areas. Surface area, of course, means any portion of the B, C, or D airspace that starts at ground level. If taking off or landing at an airport, any officially reported ground visibility at the airport (such as a METAR) must also be at least one mile. 14 CFR 91.157 goes into more detail.

By Request Only

With lower minimums comes increased risk. Therefore, a pilot must specifically ask ATC for a Special VFR clearance. We controllers cannot initiate a SVFR clearance. Doing so would be accepting liability in case an inexperienced pilot winds up in weather below what he can handle.

Since 73A did outright request a SVFR clearance, I assumed he knew what to expect. I cleared him using the standard phraseology: “N4173A is cleared out of the Class C surface area to the west of the airport. Maintain Special VFR conditions at or below 1500 feet. Departure frequency 117.4. Squawk 5121.” The two key components are a direction to exit the airspace and an altitude restriction to keep him at least 500 feet below overflying IFR aircraft.

On paper, it all kind of sounds like a get-out-of-jail-free card, doesn’t it? Fly in sub-VFR weather conditions? No instrument rating required? No IFR flight plan needed? Just call up and ask ATC and get a Special VFR clearance?

All that is true. There is a big catch, though: in the ATC world, VFR aircraft—even “special” ones—have less priority than IFR ones. When the weather’s so bad that Tower can’t see the airplanes, ATC has to operate with far more restrictions. This can result in some delays for Special VFR airplanes, as 73A was soon to discover.

Spread ‘Em Out

Controllers assume that IFR aircraft could, at any moment, be flying blindly through clouds. To ensure separation between IFR flights when visual separation isn’t available, tower and approach controllers are required to separate them from one another by a minimum of 1000 feet vertically or three miles horizontally. (Enroute center controllers need five miles.)

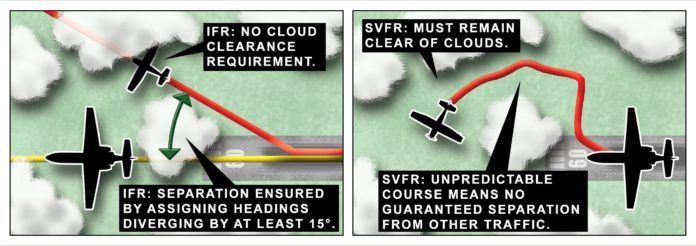

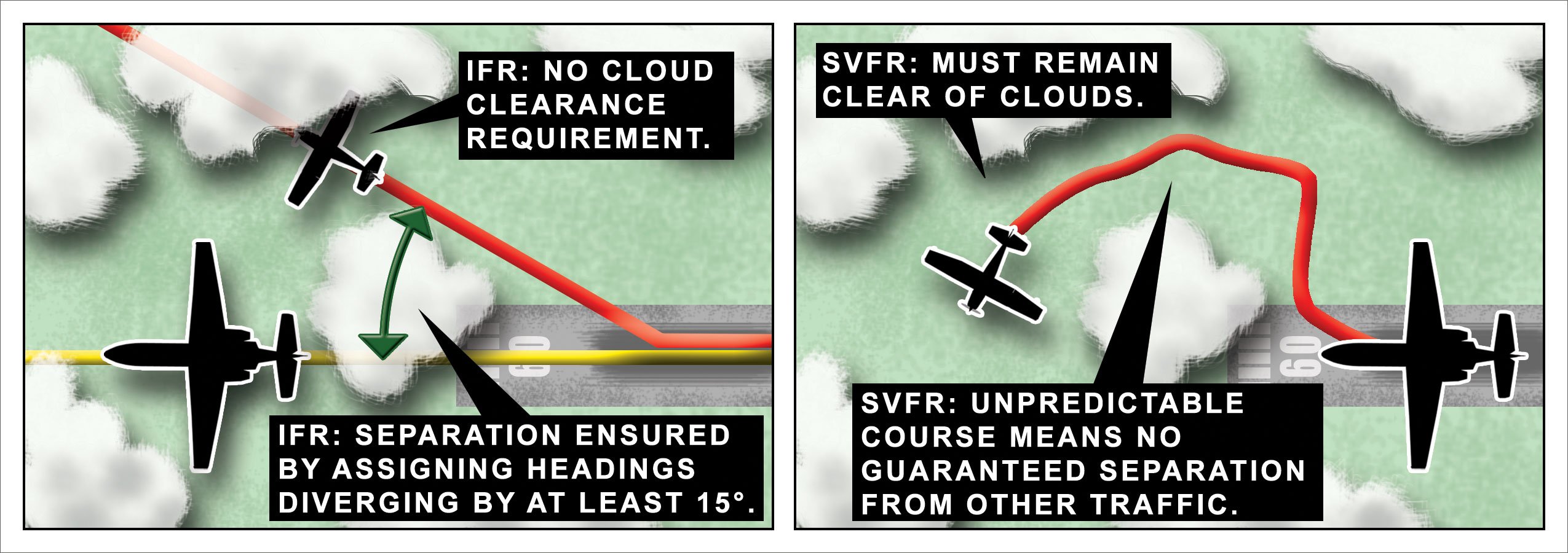

Unlike center controllers, tower and approach controllers have an additional tool to separate IFR traffic: headings that diverge by at least 15 degrees. Imagine that on this cloudy morning, Tower’s got an IFR Cessna 172—emphasis on IFR—number one for takeoff. An IFR Embraer regional jet is number two. Tower clears the Cessna for takeoff on heading 300. Once he’s airborne Tower instructs him, “Report established heading 300.” As the Skyhawk disappears into the overcast, he reports on that heading. Tower then clears the Embraer for takeoff on heading 280.

“Wait,” you might be thinking, “won’t the fast Embraer overtake the Skyhawk and get closer than three miles and a thousand feet?” Naturally. “And the Skyhawk’s also in the clouds, so you can’t use visual separation?” Correct.

This operation is both legal and safe because the Cessna’s locked on a heading that takes him north of the Embraer’s assigned flight path by at least fifteen degrees; in this case, it’s twenty degrees for windy wiggle room. If both planes do as instructed, there is simply no way for them to hit.

One In, One Out

Now, let’s make that Cessna our Special VFR airplane, N4173A. I taxied him out to the runway and he called ready. If the runway spacing exists, could Tower just clear him for takeoff with those airliners coming in on the ILS?

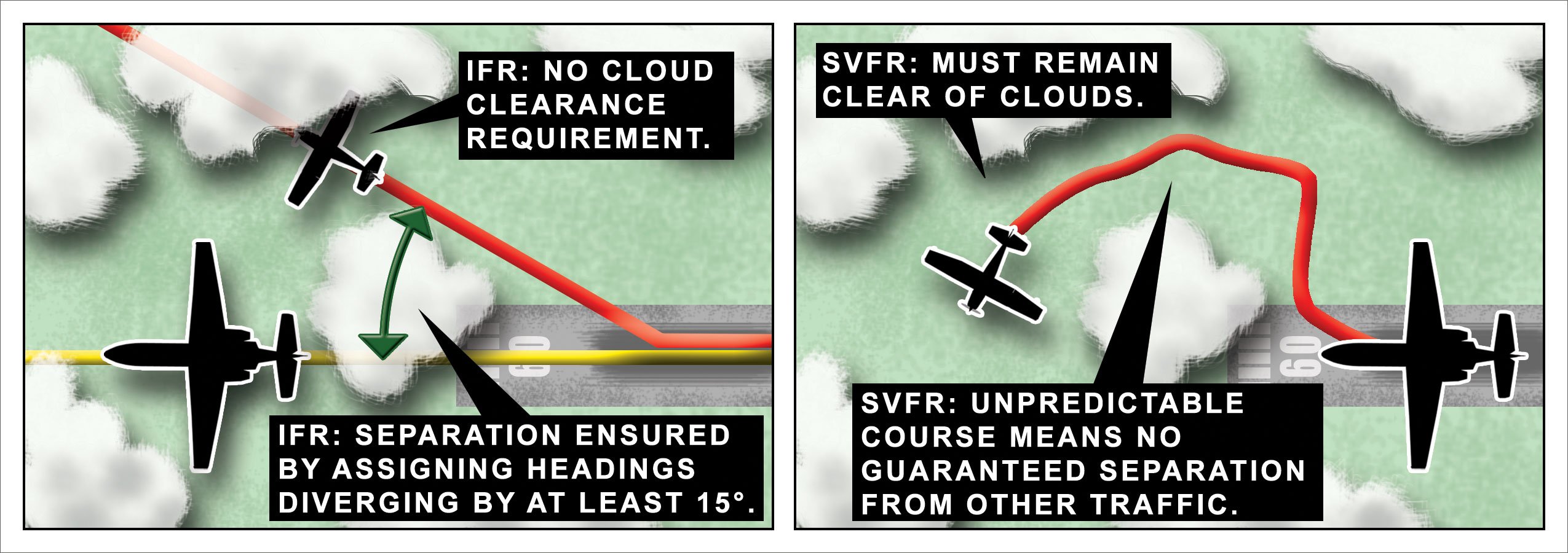

Recall that I’d given 73A a Special VFR clearance to the west. Sure, the Cessna pilot intends to go in that direction. However, he may have to twist and turn like crazy to stay clear of the clouds as required by 91.157, maybe even going towards the final approach course or back across the departure corridor.

Because his flight path is completely unpredictable, our regs require us to make sure there are no other airplanes airborne within the Class C surface area. To clear him for takeoff would involve Tower holding any other departures on the ground and Approach keeping all arriving airplanes outside of the Class C inner ring until the Cessna 172 exits the airspace.

With the stream of IFR airliners inbound, some already inside the Class C, Tower simply couldn’t let 73A depart. It’s neither legal nor safe. We’re also not going to tell a bunch of airliners to go missed approach just so we can depart one SVFR airplane.

Priority of Duty

Since the presence of a single airborne SVFR airplane will shut down an entire airport until it leaves the area or lands, the FAA allows ATC to permit or deny SVFR requests at their discretion. Certain major airports prohibit it entirely, as AIM 4-4-6 (e) states, “due to the volume of IFR traffic.”

Even in airports like ours where Special VFR flights are generally permitted, our requirement to sterilize the airspace for them means they still get moved to the back of the line behind any IFR traffic. The ATC regulations state it explicitly in 7-5-2 (a) of FAA Order 7110.65: PRIORITY: SVFR flights may be approved only if arriving and departing IFR aircraft are not delayed.

I originally told 73A that he could expect a 10 minute delay or so because of the stream of inbound IFR airliners. That’s not just me being courteous. Paragraph 7-5-2 goes on to state: Inform an aircraft of the anticipated delay when a SVFR clearance cannot be granted because of IFR traffic. Do not issue an EFC or expected departure time.

Well, no sooner was the last of the inbounds coming across the final approach fix than I had a pair of departing IFR airliners and one IFR Beechjet 400 call me for taxi. As the rules state, IFR traffic takes priority. So I taxied them to the runway via the parallel taxiway on the opposite side of the runway from 73A. The first jet was ready at the threshold just as the last IFR arrival was touching down.

Now, Wait Some More

Now, Tower had to make a decision. The Cessna had been waiting a while at this point. The jets just got to the runway. While generally we operate under “first come, first served” procedures, rules like 7-5-2 (a) change the game.

In ATC we’re often trying to pick the lesser of two evils. Option one: Tower could clear the SVFR Cessna for takeoff and delay all three of the IFR aircraft—and the hundreds of passengers on the airliners—the five minutes or longer until the Cessna cleared the Class C surface area. Option two? Make the Cessna wait a little bit longer and bang the IFR jets out as quickly as possible using diverging headings.

Tower chose the second option. He knew that if he cleared the Cessna for takeoff just as the last jet crossed the runway departure end, he could safely bet the preceding jet’s speed would have it out of the Class C surface area by the time the Skyhawk was in the air.

“N73A,” Tower said, “it’ll just be a couple of minutes. You’ll be number four for departure.” He’d just cleared the first jet to go.

“Alright. Just trying to get home here.” We could hear his exasperation now. We felt bad for the guy, but it just didn’t make sense for the operation to let him go first. We have a specific priority of duty to which we must adhere.

Explore All Options

Finally, as the last jet departure disappeared into the clouds, Tower cleared N4173A for takeoff. All in all, the Cessna had put about fifteen minutes on the meter sitting at the hold short line.

On paper, Special VFR sounds like a way to cheat the VFR minimums. As we’ve seen, though, any advantages can be seriously curtailed by the presence of other traffic.

What other option might have been available to 73A? A local IFR clearance to his destination airport would have gotten him out between the airliners just by locking him down to a heading that diverged from the other traffic’s courses. If you’re facing a similar dilemma—go SVFR or popup IFR—I’d strongly side with the IFR.

However, doing so could lead to other complications. Does the destination airport have an instrument approach? With the solid overcast and visibility there was no guarantee he was going to get a visual. Our local IFR minimum vectoring altitude is 1700. If there was no published procedure, he could be stuck above the clouds burning time and gas looking for a hole.

In this case, 73A’s airport didn’t have an approach. Special VFR was his only option, and it got him home underneath the overcast. When your options are limited, it’s always good to pack a little extra patience in your flight bag.

Tarrance Kramer does his best to minimize SVFR inconveniences while keeping terminal traffic flowing.

Helicopters are a unique type of aerial creature. Recognizing their flexible flight characteristics, the FAA lets them operate under their own set of Special VFR rules. Right off the bat, they don’t even need one mile of flight visibility for SVFR.

In most cases, though, ATC will still need to sterilize the airspace. The exceptions are helicopter operators who have specific letters of agreement (LOAs) with ATC facilities concerning SVFR ops.

A local example is our air ambulance helicopter operators. They’re based at a couple of hospitals inside our inner Class C ring. When they get called to an accident scene, they don’t have time to sit and wait for the airspace to be sterilized. These guys need to get out and get back in with their patient.

In our LOA with their company, we negotiated specific routes using prominent landmarks that will keep them away from our IFR arrival and departure corridors. The LOAs use the separation minimums specified in FAA Order 7110.65, paragraph 7-5-3. The helos are required to stay one mile away from any IFR aircraft inside our Class C if the airplane is more than a mile from the airport. Separation minimums drop to half a mile if the IFR traffic is inside a mile from the field.

What if that helicopter operator has more than one helo needing to come or go SVFR? This is common with sightseeing helicopter companies in major tourist areas such as Hawaii or the Grand Canyon. Considering how helos swarm like bees around airports in those regions, a sterile airspace requirement would hurt their business. If a helicopter isn’t turning its rotors, it isn’t turning a profit, either.

Once again, 7110.65, 7-5-3 has it covered. If the helicopters are headed more or less in the same direction, ATC is required to keep at least one mile between them. However, if their courses diverge by more than thirty degrees, we only need to space them by a whopping 200 feet. Those 200 feet can be determined either by markings on the ground, or—get this bit of clarity—simply telling one helo to stay 200 feet from the other. Who knew the FAA rules could be so, you know, logical? —TK