It’s easy to lull yourself into believing you’re IFR proficient just because you’ve logged cloud time recently. Set up a real proficiency program and you’ll never fool yourself again.

Five years ago I adopted a different kind of recurrency routine for myself. It did away with the annual three days of fire-hose drinking and associated abuse and replaced it with a monthly program that would cover all the details over the course of a year. I wrote about it in July 2007 IFR.

From where I sit five years later, I can tell you it’s worked, and worked well. Experience has led me to change the program a bit, but at its core, the concept is the same. I’ve also come to believe that this kind of a program has great hope for keeping pilots current and safe, while empowering them to get more utility out of their aircraft at the same time.

High-Stakes Game

We preach that being proficient is important. But we often overlook how even casual rust can precipitate disaster. Last summer an experienced pilot with a long career in aviation suffered an engine failure at altitude in VFR conditions in his Cessna 421. He responded ably and headed for a good airport, but on short final he went to full flaps.

The increased drag led to a crash short of the runway. He and his family of seven died. I don’t believe a recently recurrent pilot—one who had recently practiced a single-engine approach—would have made that mistake.

It seems that the stars must align to stay truly proficient. You have match schedules with a qualified instructor or safety pilot. You or they must have the right equipment. If you fly rather than sim for training, the weather must cooperate. It’s easy to see why consistent recurrent training can be a problem.

Without a mandate from your insurance company or a ready-made plan, it’s hard to know where to start. “Should I fly with Sam or Susan as my safety pilot? My kids have Microsoft Flight Simulator 93, maybe I’ll try that. Oh, wait, there’s a guy at the next airport over with a sim.” It’s dreadful to wrestle with this even once let alone over and over.

But, really, the biggest impediment may be fear. It’s embarrassing to see our shortcomings, especially in front of another person. So we delay for another month. And then another.

Progressive Maintenance

Some aircraft owners maintain their airplane on a progressive-inspection basis. Proficiency in pieces is the equivalent of that for maintaining IFR skills.

For me, a set schedule is the keystone in the Roman arch. So, on the first Saturday of every month, I train with an instructor on his sim from 7:00 to 9:30 in the morning. The schedule is set until … well, forever. I never cancel, but I occasionally reschedule.

My instructor has years of IMC missions and simulator training, and a good bedside manner. A low-time, build-the-hours instructor isn’t likely to work for this scheme. My instructor also has a simulator that’s qualified for IFR recurrency, with Precision Flight Controls, X-Plane software and flat-panel display with an instructor’s console. I fly a G500 glass cockpit, and the sim I fly has a “six pack.” This doesn’t matter to me. It’s still valuable for basic needle, ball and airspeed emergency training that would be hard to do in the air.

As the first Saturday draws near, I imagine what I’d like to do. This includes problems I’ve encountered in flight and reliving accidents that I’ve read about. We have an unstructured discussion for about 40 minutes and set up one or more scenarios to fly with emergencies. We fly them with creative additions from my instructor, such as a wake-turbulence encounter on low approach. We record and debrief what we did.

Five years ago, that alone constituted my recurrency. Since then, I’ve learned that other productive, fun and motivating activities I do also figure into the proficiency picture. I attend and sometimes lead a monthly IFR club meeting (www.ssasba.com). I read IFR, Twin Cessna Flyer (I fly a T310) and other aviation pubs that offer real insights. I’ve started a monthly small-group discussion to take IFR’s Killer Quizzes. Doing them solo is too hard. I use and update for me a quantitative risk-assessment tool. I attend Twin Cessna Flyer annual workshops on engine and airframe maintenance. Even interactions with vendors such as Garmin or Jepp (in person whenever possible) or my own maintenance shop have a place.

Proof Positive

Five years ago, I was tentative about flights that were really within the reach of my equipment and capability. I made mistakes, some scaring me. My biennial flight reviews were uncomfortable, especially when the examiner simulated engine failures in my Cessna T310 on takeoff in actual IMC at 700 feet.

With proficiency in pieces, I’m safer and more comfortable than ever. When I make mistakes—and, of course, I still do—they’re less serious and I make fewer of them. I usually commute twice a week to clients within two-and-a-half hours from my Santa Barbara base. For 14 of the 15 years I’ve owned my 310, I’ve never been late for a client meeting, but these days I achieve a dispatch ratio over 99 percent. When people quip, “Time to spare, go by air,” I say, “Thankfully, that doesn’t apply to me.” That said, I would have a lower dispatch ratio if I still lived in Buffalo.

Recurrent training isn’t the only cost of keeping that high dispatch ratio (maintenance is easily the highest). But it’s got the best ROI. I spend $200 and a 15-mile car ride to the airport. I also find myself saying on a Friday, “Nuts. My session is a week from Saturday, not tomorrow.” That’s as much a credit to my instructor as anything, but the point is that the training is social and fun as well as effective. The best part of my flying, besides landing in bad weather, is my monthly sim session.

While I’m proud of my dispatch record, it’s imperative to say that I’m not driven to achieve it. Safety—reducing mistakes—is my driver. The threat of dire consequences is a lousy motivation to do things right. Getting better at something we’re passionate about is much more compelling.

DIY Training Design

When I first wrote about this system, many IFR readers contacted me asking, “How can I do that?”

Start by quantifying your objectives. Santa Barbara has wonderful weather. But low stratus and fog are constant threats. In the winter, there’s heavy rain and a low freezing level. I train for that. You might train differently.

Next, find an instructor with a sim. A sim is complicated and requires an instructor who knows how to make it work well. Find an instructor who can discourse, not just instruct the ABCs. Don’t settle for OK. Search until you find the right situation, even if you have to travel a bit to get there. Set a schedule. Stick to it. Make up every session you miss.

Design a program where critical items are practiced repeatedly (like engine failures in a twin) and others are covered periodically. Zero-zero landing practice isn’t something to do every month, but it improves all of your approach skills. Likewise, develop a risk assessment form and practice with it on your sim sessions. In mine, risk is quantified; if total risk is over 15, I use a dispatcher; if it’s over 25 I don’t go.

Dispatcher? Yes, your friends matter here. An experienced pilot, likely an instructor, who knows you and your equipment can help you assess difficult missions in your real airplane. Getting friends in with you on your proficiency program helps keep you engaged and attending (like a workout buddy) and may push down the total cost a bit.

Not Perfect, or for Everyone

Proficiency in pieces has weaknesses. It may take a while to find a suitable sim and instructor. Even a good sim isn’t an airplane, and its avionics and systems are unlikely to be a perfect match to your own. You need at some consistent real-stick time in real-airplane IMC to stay proficient. Specifically for twins: The rudder forces for engine-out training in the sim aren’t nearly enough to feel real.

For your flying equipment, your insurance company may require Flight Safety or CAE. But you can still take the best of what they offer, such as great system training, and supplement with your proficiency program to fill in the gaps.

You can also argue, as one person told me, “This is overkill.” I defended, “Suit yourself. For me, it’s fun.”

Binge training vs. A proficiency diet

Six-month recurrency works well for professional pilots because they’re using those skills every workday in-between sim sessions. But for the average GA pilot, a diet of smaller training snacks, eaten more often, may work better than an occasional four-course meal.

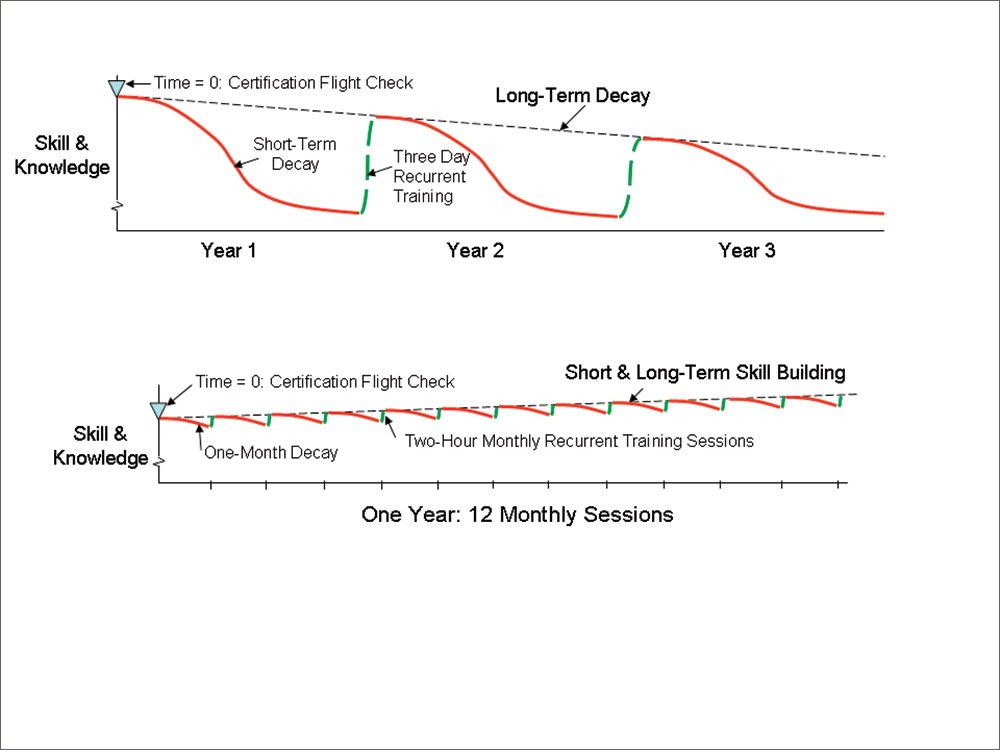

The problem isn’t the three days of immersion training so much as the gap in between. Proficiency of most GA pilots probably peaks with their last new rating. (Time=0 in the figures below.) From then on, proficiency wanes. For someone flying 50 to 100 hours a year, even with annual recurrent training, the result is still periodic, short-term decay and steady, long-term decay.

I believe recurrent training can arrest short-term skill decay and, in addition, replace long-term skill decay with long-term skill building:

The USAF requires their pilots to fly with an instructor in an airplane if they haven’t flown in the last 45 days. Ditto if they haven’t flown an instrument approach in 30 days. U.S. airlines train once or twice a year. Pilots who fly the most train the most. Pilots who fly the least train the least. That’s backwards.

Digestion Issues

Whether you drink from a fire hose or do an occasional sim session, rarely is there a chance to develop new or advanced skills or to refine existing skills to the level of a professional pilot. Unless you’re working for a rating, there just isn’t enough time for drill and practice. This kind of monthly training makes time for just that kind of practice.

There appears to be a groundswell of new initiatives around improved flight instruction and ab initio training. The more of that the better everyone is, because instructors who regularly touch students can make an immediate impact. But this system will also rely on more and better simulators. That’s another plus for proficiency-based training.

When I told my good friend who headed up marketing for years at Flight Safety about my progressive recurrent training, he said, “That’s good. Most airlines train once or twice a year. Qantas trains four times a year. They’ve never had a fatality.” That’s a noteworthy training cycle when you consider

how much day-to-day flying airline pilots do.

How can a non-professional pilot who flies single-pilot IMC, far less often, and in less-capable equipment do anything less? —F.R.

If you don’t practice it, you’ll likely screw it up

A 747 crew took off from San Francisco into a low ceiling loaded with passengers to Australia. At 400 feet in IMC their number one engine suffered a compressor stall. Everything shook so hard the instrument panel was a blur.

In response to the left bank caused by left engine-out yaw, the first officer rolled right with aileron but not rudder. That exacerbated the already-advancing sideslip and further killed lift from the fuselage-blanked left inboard wing root. Right aileron also commanded up-spoiler on the right wing, further reducing lift. The airplane sank. Police switchboards lit up as residents saw the belly of a 747 up-close and personal.

The airline trained only for V1 engine cuts on the runway. A captain and first officer of a 757 for the same airline later told me, “The last time I did an engine-out after takeoff was in the military.” For the captain it had been 25 years and for the first officer 15 years. —F.R.

Frank Robinson also flosses his teeth and eats his vegetables. He claims those are fun, too.