For this sim challenge, we’re back in the mountains because it’s just so much fun in the sim. You’ll fly two short hops over the Rocky Mountains. The trip begins at in Kremmling, Colorado (20V). Then, you’ll stop at Eagle (KEGE), on the way to the notorious LOC approach to Aspen (KASE).

You’ll need a plane that can sustain the high climb gradients these mountain departures require. Something turbocharged is a good bet, but normally aspirated engine(s) add mixture management and dwindling horsepower to the challenge. Both popular sims include a Beech Baron which works well for this scenario. If you don’t fly twins, they fly pretty much like singles until an engine fails, at which point they become one with no climb rate—don’t fail an engine.

For the first leg, configure the weather for three SM visibility and an overcast layer at 8600 MSL. Set surface winds 270 at 10, increasing to 310 at 25 by 13,000 feet. One approach is NA at night, so make it daytime. Trust us, this flight is challenging enough in marginal daytime VFR weather. Don’t make it too hot to climb either, or so cold that icing is an issue.

You can use PilotEdge for live ATC on this adventure, or you can fly it on your own. PilotEdge adds to the challenge by adding realistic ATC workload and a dynamic element. Just like in real life, you won’t know exactly when you’ll be vectored off a departure, receive a speed instruction, or be thrown an awkwardly-timed approach clearance.

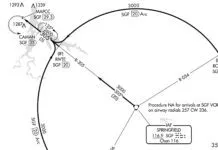

The actual flight instructions are simple: Depart 20V using the ODP, which takes you to the RLG VOR. That’s a feeder for the LDA Runway 25 at KEGE. Fly that approach to a full stop. While you’re on the ramp, raise the overcast layer to 10,700 MSL. Pick whatever departure you want (and your airplane can manage) from KEGE. Find a route that connects that departure to the LOC/DME-E at KASE. Fly that approach to a full-stop landing, taxi to the ramp, shut down, and reflect on your life choices.

Here are some questions to help with that self-reflection:

20V Departure

How did you know you’d clear the rocks on the 20V ODP? Do you have other options? When did you depart the procedure on course? How much climb rate did you need after departing the VOR?

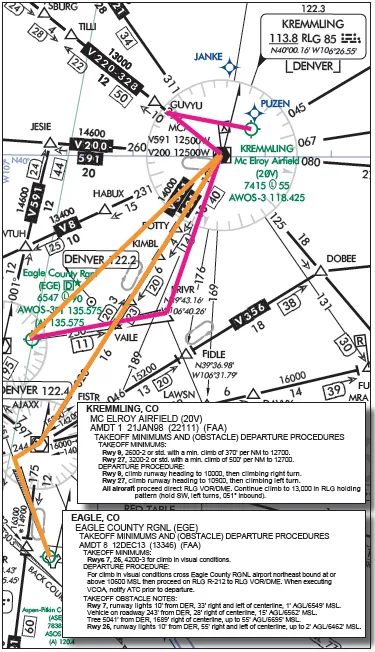

The ODP for Runway 27 requires a climb of 500 feet per NM (FPNM), all the way to 12,700. At 120 knots groundspeed (2 miles per minute) that’s 1000 FPM. At 90 knots it’s 750 FPM. It’s groundspeed that counts, and at least the first part of the climb is into a headwind. On the other hand, true airspeed (and thus groundspeed) increases by more than 20 knots at 10,000 feet and over 30 at 14,000. The above-standard temperatures that you must’ve set to avoid icing conditions will add a few knots, too.

Per the Runway 27 ODP you must climb at least 500 FPNM to 12,700, after which the climb must continue at least 200 FPNM. If weather was at least 3200-2 (it’s not), a 200 FPNM gradient will work all the way up because you could see and avoid any obstacles the ODP barely skirted. Either way, you must also follow the departure procedure to the RLG VOR, where you must climb in a holding pattern to 13,000 before starting the approach transition to KEGE.

POH charts for climb rate, plus time and distance to climb, can help. They usually assume max gross so they’re a conservative starting point. Most important is knowing your airplane. The climb gradient data field on an EFB can help … as well as a terrain screen.

Did you manage the climbing holding pattern correctly?

It’s a hold southwest of RLG, likely requiring a parallel entry. ODPs describe VOR holds in terms of the inbound direction—051 degrees in this case. If you build the hold in your GPS, make sure you enter that correctly. You need to climb to at least 13,000 feet before proceeding on course, but that doesn’t mean 13,000 is a safe enroute altitude. Here, you’ll need to continue climbing to 14,000 on the approach feeder leg after RLG.

KEGE Approach

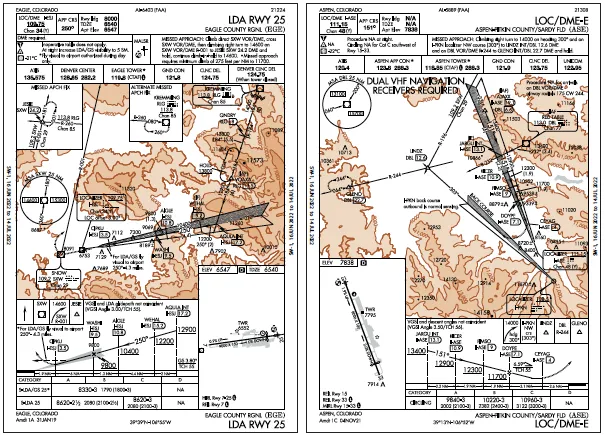

Did you fly the hold at VOAXA?

This is a relatively rare “arrival” hold, not a hold in lieu of procedure turn because it’s not bold like a HILPT. You’d only fly it when assigned by ATC. Since it’s commonly assigned, its depiction on the chart allows ATC to simply say, “hold at VOAXA as published.”

What did you do at DA? What would you do at night?

This LDA approach is one of the few with a glideslope. That also means you’re flying to a DA, not an MDA. DA is where this approach gets a little weird. You’ll be more than 4 miles from the runway, so you won’t see it with today’s 3 SM visibility. Normally you’d have to go missed. This approach has an asterisk by the LDA/GS mins to a note in the profile view “fly visual to airport 250-4.3 miles.” This allows you to continue without the airport environment in sight so long as you have 3SM, are in a position to make a normal descent, and are reasonably assured you can navigate to the runway visually.

There’s nothing stopping you from continuing to follow the localizer and glideslope on that visual segment, but you’d better be sure it will work and you must remain visual while you do it. Since the missed approach begins back at DA, you’re on your own and in a bit of trouble if you need a missed approach later.

The asterisk also connects to the notes section where it says the fly visual is NA at night. But the approach isn’t. You just need 5SM vis, which means you could see the runway from DA. Hopefully.

If you flew this without the GS, how close would you be to the runway at the MAP? Could you land straight-in if you were VMC?

This is a highly unusual approach. As such, the profile depiction is awkward at best. When we inquired, the FAA agreed that the depiction at minimums is in error. So, ignore the profile view for this analysis, and look solely at the other information. On the glideslope the DA is at 8330 feet and 4.3 miles from the runway, at which point the fly-visual portion begins. This is stated in the asterisked note. But the non-precision MDA is higher but closer—8620 feet at CIPKU, 1.9 miles from the runway, at which point with the requisite 2.5 miles of visibility, the runway would be in sight.

As for landing straight-in from MDA at CIPKU, you’d still be 2080 feet above the runway. That’s descending better than 1000 FPNM: steeper than a 10-degree slope. Ain’t gonna happen. Like many non-precision approaches, remaining at MDA all the way to the MAP means you’re too close for a landing using “normal maneuvers.”

KEGE Departure

Which departure did you choose?

Eagle has three SIDs, but they’re all designed for aircraft with lots of performance. The lowest is still 740 FPNM to 10,200 for departing Runway 25. That’s probably a stretch in your airplane (although a couple could be fun with just two VOR receivers), but there is a better option.

The Visual Climb Over Airport (VCOA) only requires remaining in visual conditions above the airport until crossing the airport northeast bound above at least 10,600 before joining the RLG R-212 to the VOR. Naturally you need high enough ceilings to climb visually to 10,600 MSL, which is why the procedure requires at least 4200-foot ceilings. That’s about 10,700 MSL. Fortunately (and not coincidentally), that’s exactly where you’ve set the weather.

What if the/an engine had failed?

There’s no requirement for multi-engine Part 91 operators to have a backup plan for a single-engine climb. You’re probably out of luck in just about any piston twin at this altitude. At least on the VCOA you’ll be near the airport. Single or twin, you could find a way to dead-stick back to the runway.

KASE Approach

What route did you choose to join the approach?

If you flew the VCOA to RLG, you likely flew back down V361 to begin the approach at DBL. Arriving there at the MEA of 14,000 means some aggressive descending to catch up with the already steep approach profile. It also demands a tight turn to join the localizer. Aspen Approach has MVAs between 11,000 and 13,000 in the area, so if you used PilotEdge ATC they likely cleared you direct to DBL or AJAXX well before reaching RLG. That’s both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, you might get the simpler AJAXX transition, or at least a lower altitude at DBL. On the other, you’d have much less time to get ready for the approach. Hopefully you briefed it and set up as much as possible before departure.

Did you anticipate the steep descent rate? Did you land straight-in or circle?

We’ll go out on a limb and say that if you didn’t anticipate the steep descent, your approach probably didn’t succeed. Your clue was circling minimums only for what looks like a straight-in approach. That’s because the 6.59-degree angle from DOYPE to the runway equals nearly 1400 FPM at 120 knots.

But wait … there’s more. We already mentioned 120 KIAS is more like 150 KIAS today. The west wind is a net tailwind, adding even more knots. What’s it now? 1700 FPM? More? Yikes. This would be a good time to adjust your performance profiles for a steeper, slower approach. Hopefully Aspen isn’t your first time practicing it.

It’s a circling-only approach, but as a rule pilots don’t circle at Aspen. If there’s a tailwind for Runway 15, you either make it work anyway or go somewhere else. There’s just too much that can go wrong in the tight valley. Sure, the circling minimums protect you from hitting anything, but they’re over 2000 AGL. At some point, you need to come down and land visually. There’s plenty to go wrong on the steep straight-in landing too, but it’s the lesser of two evils.

What if a grizzly bear sat down on the runway on short final?

Much like at KEGE, a late go-around here puts you in a world of hurt. You’re three miles beyond the MAP and 2000 feet below the MDA. There’s no way you’re gonna be able to join the published missed. Sometimes a departure procedure—if briefed—can save the day, but not here: The only departures are for Runway 33. Your best bet might be entering the traffic pattern to come back to Runway 15. But that includes all the hazards of the circle-to-land, without the protection of the MDA. Bottom line: you better be certain you can make a landing before proceeding beyond the MAP.

By the way, check out the missed approach procedure. It’s a climbing turn to intercept another localizer, set up specifically for the missed (and several SIDs). It’s labeled a back course, but a note emphasizes that it’s “normal sensing.” That means you should set your HSI to the outbound 303° and make corrections toward the CDI needle.

Perhaps your takeaway from this challenge is that there’s no way you’d ever make this flight in real life—at least not in this weather. Good call. That’s why this is the sim, and why we call it a challenge.

Jeff Van West has flown to these airports in the real world with only a tired, non-turbo O-360 spinning the prop, but by following ridgelines VFR in CAVU conditions. Ryan Koch has flown these approaches in all sorts of horrible weather dozens of times, in a variety of aircraft, and with failures … in the sim. We’re not sure who had to work harder.