Recently, a subscriber sent me a note to ask about the legality of departures into bad weather. At first, this seemed like a rather simplistic question, but as I dug, the back story made it a reasonable discussion. That pilot had a career in the military. As with most large bureaucracies, its operations were rather stringently governed by restrictions and minimums, often more stringent than others might find necessary. The pilot had since retired, converted his military experience to civilian purposes, and now was enjoying flying general aviation.

So, the question, asked with some disbelief, concerned the legality of launching in a single-engine piston aircraft into a low overcast. The pilot even offered that perhaps there was a minimum equipment requirement, such as turbine power, before that became legal. Or, perhaps one needed a twin, and could that legally be a piston-twin, before launching into the scud? The discussion that ensued is worth exposing to your scrutiny.

Regulations

Let’s limit ourselves to the FAA’s regulations with the understanding that regulations elsewhere in the world vary, but are generally similar in this regard. There are two pertinent regulations.

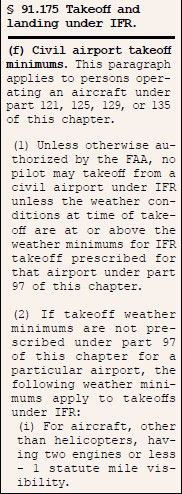

Basic equipment requirements are covered in §91.205, but only have to do with things like gyro instruments, navigation, and the like. No requirements are placed on the type or number of engines. Then, Paragraph (f) of §91.175, “Takeoff and landing under IFR,” covers “Civil airport takeoff minimums,” specifically weather. It applies to commercial operations only; general aviation (Part 91) has no restrictions.

So, it is perfectly legal for a Cessna 172 or any properly equipped piston single to take-off on an instrument clearance when the departure airport weather is low. Not only is that legal, there are no additional requirements like a take-off alternate.

It’s common for instrument students to occasionally train for a low-visibility takeoff on runways that offer some precision lateral guidance, like a localizer. I remember sitting at the end of the runway with the localizer dialed in, and having my instrument instructor tell me to put the hood on for the takeoff. The result was quite unnerving, but successful, if white knuckles can be an element of “successful.”

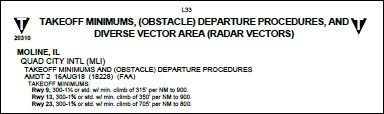

In a discontinuity between commercial operations and general aviation that is fund throughout the U.S. regulations, commercial operators do have departure weather minimums. In fact, there’s one right there in §91.175. That same Paragraph (f) says that we need a minimum of the weather prescribed in Part 97, the instrument procedures. Lacking an instrument procedure, an aircraft with two or fewer engines needs at least one statute mile of visibility. I should note, though, that the operators’ OpSpecs often permit lower weather minimums. At the airline where I flew, we were permitted 600-feet of RVR for a takeoff, and we regularly practiced with 500 RVR in the sim, which was very definitely a sphincter-tightening exercise.

Risk vs. Reward

Everything in life is a risk. We could stay in bed all day to isolate ourselves from outside risks, but even with that there’s a possibility of something falling from the sky, crashing through our roof, and landing on us. This actually happened a few years ago when an insufficiently secured life raft fell from a helicopter

and crashed through a bedroom roof in Florida. Fortunately, nobody in the house was injured.

For most of us, though, a life spent hiding under the covers in bed wouldn’t be very rewarding. So, we pursue various endeavors. Some of us actually operate machinery that flies through the air. To do that, we undertake substantial training and invest heavily in the safe condition of our vehicles. We also usually make reasonable attempts to identify and mitigate—to some degree—the inherent risk of breaking the surly bonds.

I’ve informally noticed that many of us tend to define acceptable risk for flying in terms of our experience and the equipment we fly. For example, back when I was a wee instrument pilot flying an older Mooney, my wife and I used to regularly fly from our base on the Central Coast of California down the coast to have dinner at a lovely beachside restaurant within walking distance of the Santa Barbara airport. The late afternoon trip down was usually flown in good VMC. The trip home, however, often wasn’t.

Throughout much of the year, the California coast is subject to a low marine stratus layer—coastal fog. It would often arrive in early evening. This meant that our trip home was in IMC, at night, over water and coastal mountains. At first, I took this in stride and we enjoyed many meals at that restaurant. However, after I got my multi-engine rating, the return flight became more and more stressful until it contributed one of the justifications to sell the Mooney and buy a twin.

With the twin, we felt much safer on that return flight. But, were we really any safer?

Risk Analysis

A relatively new but skilled instrument pilot might be comfortable in a 172 departing into a low overcast. If nothing went wrong—as is the norm—the outcome certainly made the risk seem acceptable. Would the same departure in a turbine-powered single be safer? How about a piston twin? … or turbine twin?

So, while some of us might feel comfortable departing in marginal weather in a piston single, others might need a twin, while still others might not feel comfortable without a turbine twin or even a jet. Aircraft engines are remarkably reliable and engine failures are seldom the cause of accidents. But remember the simple fact that in a twin you’re twice as likely to have an engine failure as in a single. Who’s to say what is unsafe?

The pilot (and the passengers) must make that decision. Each of us should carefully evaluate the pros and cons of each action in an aircraft, and weigh the likelihood of an undesirable outcome against the measures needed to mitigate the risk, and against the overall utility of the flight. If you’re reading this, obviously you’ve found some balance between useful and risky.

That Low-Visibility Takeoff

In reality, the likelihood of any problems even on a zero-zero takeoff in any type of aircraft, is extremely low. That might be acceptable for some of us, yet way too much risk for others. If it’s too high for you, there are a couple other limits that some pilots adopt.

First is to use those commercial requirements. They were written trying to make commercial air travel safer than non-commercial flights. So, you might opt to use those published takeoff weather minimums and even to have a take-off alternate when the departure weather is below a certain point.

Others might simply require weather that permits a landing there. The weather must be above the lowest usable approach minimums.

When considering either of those options, though, consider this: In the real world, what is the likelihood of a failure severe enough to require an immediate landing, but leaving the aircraft sufficiently operational to fly a successful approach? That’s probably a distressingly slight possibility, and is probably what induces some of us to depart as low as zero-zero. They might conclude that the risk in a zero-zero takeoff is so minimally— and acceptably—greater than, say, into even 1000-1 as to be reasonable. Fact is, lose an engine below a few thousand feet AGL in any weather at all, often even in a twin, and the outcome is rarely “acceptable.”

There’s no simple answer. Risk that is acceptable to one thinking pilot might not be even close to acceptable to another. That’s life. We each must decide for ourselves if we wish to minimize most risk and stay in bed, or accept a little risk to drive to the grocery store, or even accept more risk by taking to the air. Think it through for yourself; feel free to share your reasoning.