When I trained for my private pilot certificate, 91.103 was drilled into my head. “Each pilot in command,” it says, “shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight.” The core of that is straight from the Boy Scouts: be prepared.

Now, as an air traffic controller, it concerns me when pilots aren’t aware of major issues affecting their flight. Sometimes we controllers have to be the voice of reason, preventing a pilot from doing something that may not be in his best interest. Other times, we have to hold his hand and walk him through a new situation.

Thankfully, the vast majority of our operations are routine. It’s the remainder that can make things interesting. Facing an underprepared or overzealous pilot can test a controller’s knowledge of his rules, his airspace, and his ability to think outside the box to find a safe, legal solution.

Hitting a Wall

One morning, a Cessna 210 on a photo mission came into our Approach airspace with a few sites to hit. His client was a shopping mall developer who needed some aerial shots of their properties. Of course, those palaces of commerce aren’t displayed on our radar scopes. I asked him for each target’s range and bearing from our main airport so I could visualize where he needed to go.

He listed a trio of locations. I sighed when I wrote down their details. Apparently, the Centurion pilot had not checked his Temporary Flight Restrictions. We had an air show underway at our airport, starring the six F-16 fighters of the U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds and a bunch of other performers. All three locations were within a mile of the field. Not a good place to be.

“Sir, unable those locations. We have an air show TFR in place over that airport, five-mile radius and up to 16,000 feet. It expires in four hours, at 4 p.m. local time.” I paused to let him digest the bad news. “Say request.”

In 1969, psychiatrist Elisabeth K bler-Ross published the “Five Stages of Grief” model. All five played out on my freq, starting with denial. “A what?” Anger came next. “This is ridiculous. We’d be done in 15 minutes!” I told him there was nothing I could do, and he continued. “I’ve got the client in the back and we’ve just flown a hundred miles to get here. We need to get these shots.” He progressed to bargaining. “What do we do now? Can’t we just sneak in there?”

“Sir,” I said, “I can’t tell you where to go. I’m just telling you where you can’t go.” I almost stated that the TFR was issued weeks ago, but I opted not to pour avgas on the fire. “Again, say request.”

Depression kicked in. “Alright. I just talked to my client. We’ll just have to put it down and wait it out.” At last, he reached acceptance. “What’s the nearest airport where can we grab some food? May as well make use of our time.” I gladly gave him some vectors to a nearby non-towered field I’d heard had a great lunch. Hopefully, next time, he would check for TFRs and cross-reference them with his photo locations.

Altitude Antics

TFRs aren’t the only invisible barriers in the sky. ATC’s got to contend with equally transparent regulatory floors and ceilings.

There was a Maule M7 driver who filed IFR to a local turf strip. The field had no instrument approaches, but he was hoping to snag a visual. Upon arriving overhead, his optimism was checked by a thick overcast. According to various area sensors, the ceiling was between 1200 and 1400. Complicating things, some nearby antennas made our local MVA (minimum vectoring altitude) 2500 feet.

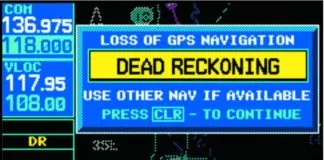

We were at an impasse. He kept begging for lower so he could try and get the field in sight. I couldn’t legally descend him below 2500 feet, nor clear him for a visual approach unless he saw the airport. He was getting desperate. As my wife can attest, mindreading is not a skill I possess, but I had a bad feeling Mr. Maule might cancel IFR and try to drop through the clouds, illegally.

So, I offered a suggestion: I could vector him for an approach into the nearest equipped airport, about 10 miles south. The field was showing 1400 feet overcast—i.e. it was VFR. Flying the approach would safely and legally get him underneath the clouds. Once beneath the deck, he could shoot a low approach, report cancellation of his IFR clearance, and proceed VFR to his original destination.

After some consideration, he went with it. Following an ILS and some scud running, he arrived at his destination, all regulations intact. If you know the rules, you can figure out ways to work within and around them to still get what you want.

Going Nowhere Fast

Both pilots we’ve met so far knew where they wanted to go. They just hit some speed bumps along the way. What happens when a pilot is really behind the curve? Those situations can feel like you’re simultaneously playing dentist and detective, pulling teeth and hunting for clues.

One quiet morning, I was working ground and clearance delivery up in the tower. A nervous-sounding Cherokee pilot reached out. “I need an IFR clearance.” Did he have one on file? “No, I’ve never actually filed one; my instructor always did it. Can you help me out? I’m on my instrument checkride. The examiner’s in the briefing room and I’m on my handheld.” On his checkride and he’d never filed before? That was a new one.

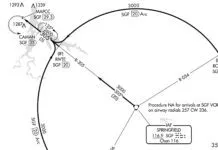

I put on my figurative Dr. Sherlock Holmes, D.D.S. hat and went to work. What did he need to accomplish on his checkride? “Practice some VOR holding first, and approaches.” I listed off the VORs in our area, and asked which one he wanted for holding, at what altitude. “The first one at 4000.” Which approaches, and where did he want to do them? He stated one outlying field and our main airport. I told him that there were GPS, VOR, and ILS approaches available at both fields. “Let’s do a VOR at the first one, and a GPS and an ILS full stop back here.”

I built a flight plan for him using our clunky Flight Data Input Output (FDIO) computer. The route led from our main airport direct to the VOR (with a half hour delay for holding), on to the non-towered airport, and then back here. In the remarks, I noted his holding and approach requests to give Departure a heads up. I then issued the clearance to him. A half-hour later, he was up in the air. He did his holding, shot his approaches and came back in.

The next day, after work, I stopped by one of our FBOs to get a close look at a P-51 Mustang warbird I had cleared to land earlier. There was a younger dude and his girlfriend there, also looking over the vintage hardware. We struck up a conversation about aviation—as pilots do—and, in its course, I mentioned I worked in the control tower.

“Oh, man,” he said, “you guys helped me out big time yesterday. I was on my instrument checkride and…” Yep—by sheer coincidence, it was the same guy. Everything had gone smoothly and he’d indeed gotten his instrument ticket. We controllers don’t often get to meet our “customers” face to face. Seeing his excitement and relief about the whole thing really made my day.

The Road to Nowhere

Professional pilots are just as human as their less-experienced student comrades. The pros can throw ATC for a loop too. I walked upstairs into the tower one afternoon to relieve the Tower controller. A speedy Citation 750 was sitting on an unused taxiway, engines turning. “Maintenance issue?” I asked. Nope. Due to weather, they wanted us to put in a new route for them to their destination, Tampa International Airport (KTPA), down in Florida.

Controllers must be intimately familiar with the airspace under their jurisdiction. This includes all the approaches, fixes, STARS, SIDS, navaids, and more that they use on a daily basis. Outside of our immediate area, things get foggy. Sure, we know general geography; Los Angeles is where the sun sets, London’s where it rises, and so forth. However, ask us about procedures at an airport outside of our airspace, and we’ll have no idea. That’s where you—the pilot—are supposed to step in with an accurate flight plan.

Ground had entered the crew’s new route into the computer. It was a series of VORs and airways, followed by a STAR, then their destination, Tampa (KTPA). The computer didn’t like it, saying the last VOR wouldn’t merge with the STAR. The crew gave him another combination of VORs and airways, then yet another, all with the same result.

Now, these kinds of issues aren’t usually that difficult to resolve. A STAR is a pre-determined route made of either navaids or GPS fixes that guides high-flying aircraft down from the flight levels to a major airport. To connect your route to a STAR, the last fix on your route should also be a fix on the STAR, kind of like an on-ramp to a freeway. Otherwise, the computer has no idea where you’re going to join the STAR.

To fix this, we usually just have to find a navaid or fix on the STAR to bridge it with the route. I loaded up KTPA’s listing on Skyvector.com via the tower cab computer. “Hey,” I asked Ground, “How d’ya spell that STAR?” He yelled back, “PIGLT4—Papa India Golf Lima Tango Four.” Weird. The Tampa STAR list didn’t have any “P” entries.

Confused, I looked east of Tampa on the Skyvector chart. Suddenly, it hit me. I typed fast, and seconds later I’d confirmed my suspicions. “Well, no wonder it’s not freaking working. He’s giving us a STAR into the wrong airport. PIGLT is Piglet, from Winnie the Pooh. He’s got Disney on the brain. It’s an Orlando International Airport STAR,” pointing at KMCO’s listing, “not a Tampa one.”

Ground diplomatically told the crew about their Goofy-up. (Sorry—couldn’t resist.) They apologized and were embarrassed as they looked up a good STAR for KTPA. None of us there had seen an issue like that before. The crew of the fastest civilian jet currently flying had confused one airport’s procedure for another and left us all scratching our heads. If we ever have another STAR-related issue, now we know another possible solution: double-check that it actually belongs to the destination airport.

Aviators of all skill levels can find themselves in a bind. Together, pilots and controllers can sort through the confusion, troubleshoot the problem, and arrive at a workable—if not always ideal—solution.

For Tarrance Kramer, playing Detective Troubleshooter is all in a day’s work while he keeps the planes apart out in the Midwest.