Exploring new places with your airplane can be fun, but sometimes that requires being comfortable with operations you don’t do often. It can also mean flying in conditions you’d consider challenging. Or, all of the above. In that case, previous experience is a plus. The more recent, the better. Even then, “recent” is a judgement call.

Alternate Shuffle

The week-long work-cation began with flying the family in the C-177RG from southern Indiana to the Tulsa area. It was a quick, direct trip in clear weather, which to your dismay turned cloudy after two days’ worth of meetings. But no matter, you and the family are free to spend a few more days together on the way home.

The first stop out of Oklahoma isn’t far: 6M2, Horseshoe Bend in northeast Arkansas. It’s adjacent to a friendly resort (complete with golf course) and enough activities for everyone to enjoy the spring weather. And just 15 minutes east is KARG, Walnut Ridge, a nice-looking airport with three runways (two of which have instrument approaches). The field got its start as a World War II Army training facility and is now public-use and even has an aviation museum.

Cool: You can file two flight plans—one from Tulsa to Horseshoe Bend using Walnut Ridge as the alternate, then vice versa. KARG is fine as the alternate for 6M2; there are no restrictions other than the weather reporting being functional. The forecast will be above the 800-2 threshold for alternate weather to comply with §91.169. (You remembered that, for now, the LPV for this purpose is not a “precision” approach.)

But there’s a wrinkle when Walnut Ridge is the destination: 6M2 is NA for the alternate. Same deal for the other small airports in the vicinity. That’s common in rural areas where resources like navaids, big runways and weather stations are unmonitored or unavailable. Speaking of which, 6M2 doesn’t have its own weather, but uses Baxter County, 35 miles northwest. And the only procedure is an RNAV-A.

Hmm…maybe hold off on that airport ’til summer, unless the weather is at least marginal VFR. You’ll check on that again. For now you can file the Walnut Ridge flight plan with another alternate, probably Jonesboro, which has the closest TAF 22NM to the southeast. Since TAFs are good for a five-mile radius, it’ll be worth checking the graphical aviation forecast to see if the forecasts agree. The GAF visibility scale uses one-to-two statute miles, two-to-three and so on, though, so “three to five” is a bit vague. As long as it’s at least three, you’ll be comfortable.

Now, just out of curiosity, can you file an alternate like 6M2 that’s “NA” if the weather is visual? The reg under §91.169 (c) comes to mind, something about “landing under basic VFR.” The MEA for the V140 airway segment that leads to 6M2 (elevation 781) is 3000 feet. Flying VFR from that point and below means the minimum ceiling at the airway would be 3500 feet MSL, or about 2700 feet as reported AGL, to enable you to operate 500 feet below the clouds and be legal. Sounds feasible and local traffic would be well under the ceiling.

But of course, there’s a catch: That doesn’t comply with (c)(1). Airports with at least one instrument approach are subject to the alternate weather criteria, the ol’ 800-2/600-2 rules. There’s no provision otherwise. The next item, (c)(2), allows the transition-to-VFR option for those airports where “no instrument approach procedure has been published.” There are plenty of those around, but the flight plan is fine the way it is.

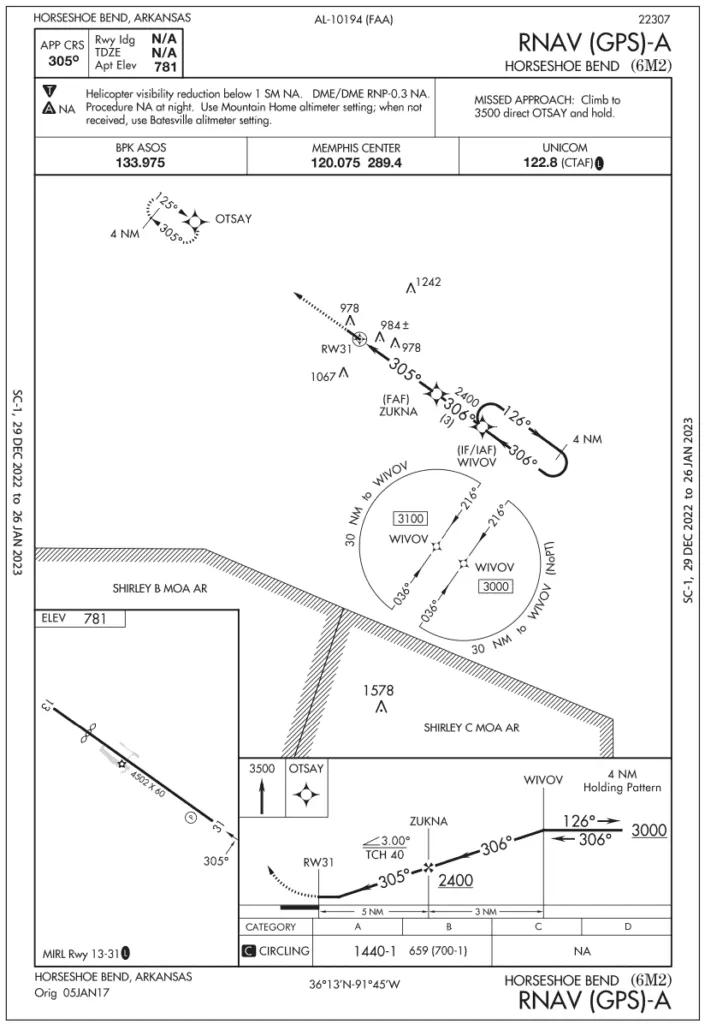

Departure time brings conditions of 1500-5 in the swath between Baxter County and Jonesboro, so you’re comfortable flying to Horseshoe Bend. It’s good enough to use the visual traffic pattern if need be after breaking off the RNAV-A. Arriving from the west, the approach will start at WIVOV with a HILPT, hold-in-lieu-of-procedure turn. While it has been a couple of years since you’ve flown an actual HILPT, you’re current from three weeks ago on holding, and this looks similar enough. Except … be sure, if so cleared, to fly the teardrop entry and continue inbound; resist the urge to continue the racetrack like you practiced last time. Now you see that after WIVOV, the approach course lines up almost perfectly with Runway 31, so it’d be great to head straight in.

Wind and Hills

But there’s a new wrinkle: A ten-knot wind from the east. Circling to 13, or land on 31 with a small tailwind component? Maybe … when’s the last time you did one of those? Might’ve been six months ago, and you’ve done this a handful of times when downwind on ILS approaches due to low weather. But you haven’t tried approaches above a six-knot tailwind component, and never on runways less than 5000 feet.

Using the correction factor in the POH, there’s a 10 percent penalty for every two knots of tailwind “up to 10 knots.” The maximum component means a 50 percent increase in landing distance, assuming weight of 2800 pounds, full flaps and “maximum braking.” It’s also assuming a speed of 63 knots KIAS at 50 feet, so use the 50-foot obstacle distances and add a margin because realistically, you’ll be a couple knots off and won’t stand on the brakes (unless you have to). If you conservatively add the obstacle and 50 percent margin, it’s 2081 feet. With a PAPI and 4502 feet available, that’s still less than half the runway.

There’s yet another wrinkle: Landing distances differ at each end shown by a displaced threshold symbol on 13. While not to scale, the airport sketch suggests the displacement eats up nearly a quarter of the runway. Up top, landing distance available is “N/A” and there’s no declared runway distance on this chart (no ).

It took some online digging, but you found a note on AirNav.com (Thanks!) that the displacement is 994 feet, leaving 3508 feet available. That’ll suffice in a headwind, with the trade-off a circling approach, which you last did, like, a year back? Yet, if the weather holds and allows a standard left-hand pattern, that’d be okay. Plus, you’ll be able to see the “rapidly rising terrain” northwest of the arrival end. Oh, that fine print on AirNav. Now you feel you need at least 2000-3, and you will stick with 31 if the winds remain light. And the pattern will still work on a go-around.

Now, even with the larger circling area required here given the on the chart, the 1.3-mile turning radius is unchanged for Category A. Meanwhile, circling radius for B increases to 1.7 from 1.5 NM, and anything faster is NA. Given your experience, you decide to not use the tailwind option if the wind component’s more than six knots. A wind check at the final fix, ZUKNA, will give you time to switch. The missed-approach procedure for a straight-out climb to the northwest will also provide a backup on approach. Beyond MDA, any go-around will use the standard traffic pattern no more than one mile out. Just don’t lose sight of those hills. Or take on any fuel.

One More Choice

During your stay, the wind reduced to six knots but shifted to the southwest. The weather further improved to 3000-10. You’ll depart on Runway 13, downwind and away from the terrain, or Runway 31, into the wind but with an immediate, low, right turn. The tailwind correction, again padding the conditions and using obstacle clearance, gives a takeoff distance of 1510 feet with what’s now a lighter weight of 2600 pounds. Climb to a pressure altitude of 2000 feet (back to assuming 2800 pounds) at 81 knots for a rate of 830 feet per minute. Now comes the task you’re best at: Take off into the wind and deploy the short-field, obstacle-clearance technique as you always do at home, and experience tells you it’ll do a little better than book. Malfunction? Not making 900 FPM? Use that VFR traffic pattern to keep climbing, or land. When you call for a clearance on the ground, explain the plan to ATC. Then, there’s no rush to call in ’til you’re safely above the terrain.

Knowing how to use the little-used tools is sure handy, but they work best with recent use and, of course, some backup plans.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. While her students call it the “Hell-PT,” she always looks forward to ordering up a HILPT (or two) during recurrent training.