Beyond controlling traffic, ATC helps prevent pilot errors and occasionally helps a pilot out of a tight spot. ATC’s union, NATCA, periodically recognizes controllers who have gone beyond the call. Here are a few of their stories.

A Chilled Cessna

Denver Center’s airspace includes the challenges of mountainous terrain, winter weather including icing, severe turbulence, IMC, and lots of traffic.

True to form, a Cessna 310 checked in. Controllers Jake and Morgan saw immediately that the aircraft was having trouble maintaining altitude due to severe icing. It was also below the minimum IFR altitude for its area. They started working the 310 toward lower terrain to the north and began treating the situation as an emergency, though the pilot never declared one.

They obtained a base report of 11,000 feet from a passing airliner. Eventually, the 310 descended into VMC. As the ice melted off the airplane, the pilot regained positive control. The 310 found good weather and flew a successful visual approach.

Jake later observed, “Bad things do happen. Pilots may know what to do, but they might not. If we are confident and calm, that might be all the pilots need to help move them from one task to the next.”

Jake and Morgan initiated action based on the aircraft’s inability to hold altitude. They kept the aircraft away from terrain and helped it descend to an ice-free altitude. Their calm confidence helped the pilot reach safety.

Taxi Turn Basics

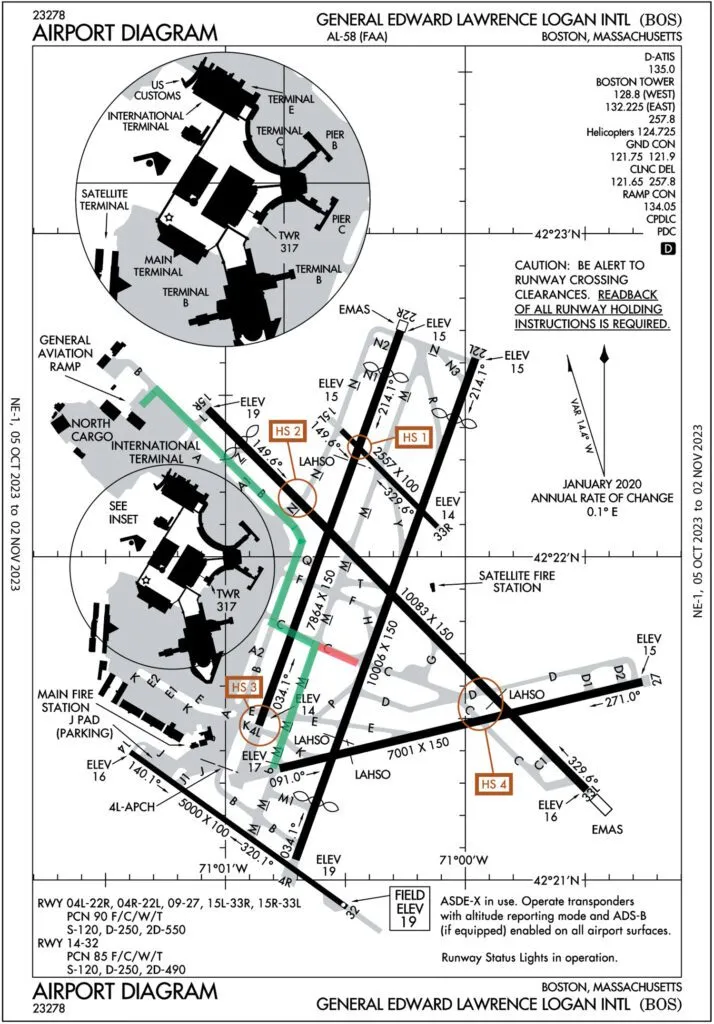

One evening, a Hawker 400 bizjet at the GA ramp requested taxi instructions from Boston Ground to Runway 9. Controller Patrick gave them a right turn onto Bravo, left on Charlie, cleared them to cross Runway 4L, then right on Mike to Runway 9.

One evening, a Hawker 400 bizjet at the GA ramp requested taxi instructions from Boston Ground to Runway 9. Controller Patrick gave them a right turn onto Bravo, left on Charlie, cleared them to cross Runway 4L, then right on Mike to Runway 9.

The pilot read this straightforward clearance back incorrectly twice. Patrick took notice. “I want to pay attention a little bit more to this particular pilot than normal.” His confidence eroded further when the pilot set the wrong code in the transponder.

The crew then failed to turn right onto Mike, which headed them straight toward Runway 4L, which had an aircraft on short final. The watchful controller told the Hawker to stop, which it did without entering the runway. Patrick turned the Hawker around and directed it to Runway 9 via a left turn onto Mike.

Controllers put lots of stock in how you work the radio, so try to be sharp. Sloppy radio work can imply an inexperienced or error-prone pilot. The Hawker redeemed itself by paying attention and obeying Patrick’s instructions.

Mitsubishi Mayhem

One evening in late 2021, controller Brian was working his usual Kansas City Center sector. This shift, however, would be different.

A Mitsubishi MU-2 going to Pueblo, Colorado, at FL 240 requested a lower altitude due to a pressurization problem. Immediately, he declared an emergency for the aircraft and cleared the MU-2 down to FL 180. After coordinating with nearby Vance AFB, he cleared it to 10,000 feet. Brian said, “Lack of oxygen is a very time-sensitive issue, so we had to get him going.”

Even at FL 180, “something wasn’t clicking with the pilot.” Other controllers recommended that he repeatedly transmit “oxygen, oxygen.” At 16,000 feet, the aircraft made a steep left turn, which looked like a possible spiral.

Brian issued a heading of 270 as the pilot began to regain control and turned west. Another pilot on the frequency added, “Descend, man, descend!” As he descended, the pilot became more coherent. He elected to continue to Pueblo and landed safely.

The pilot called Kansas Center to express his gratitude. “The controller that continued to talk to me in a calm, professional manner and kept telling me to descend over and over helped prevent me from passing out and likely [prevented] a different outcome.”

An Unwelcome Drone

In early 2021, Noah was working his radar position from the tower cab at GRO in Greensboro, North Carolina, as the tower and TRACON positions were combined for the evening.

He was lining up a Lifeguard aircraft for final approach on Runway 14 when he noticed lights that appeared to be another aircraft in conflict.

Noah asked the tower controller if he was talking to another aircraft, but he was not. With a chill, he realized it was a drone flying near the arrival corridor for Runway 14. Noah canceled the Lifeguard’s approach clearance and gave it a downwind entry for another runway.

Meanwhile, other aircraft were taxiing toward the two southwest runways, pointed straight at the drone. The controllers turned the airport flow around and had aircraft depart from Runways 5L and 5R, away from the drone.

When the drone’s flight path became erratic, ATC had to suspend GSO operations, preventing arrivals and departures. Adjacent Centers, the FAA’s Domestic Events Network, and local law enforcement were advised. After about two and a half hours, the drone departed; the pilot was never found.

Noah’s actions prevented a collision and assured the safety of the airspace. Said one pilot on frequency, “Thanks for looking out for us.”

We might add that looking out for drones is also a pilot’s responsibility, and like the drone above, most lack transponders.

Taking Advantage of COVID

In 2020, air carrier volume significantly decreased, allowing many GA pilots and instructors to make takeoffs and landings at major airports. In this case, it was Dulles International Airport.

One such flight was a Mooney M20 with a student and instructor aboard. Near IAD at 4600 feet, the Mooney’s engine quit. Joe, the controller, cleared the Mooney to turn left directly to Dulles and land on any runway. The pilot elected to land on 19C. Other controllers cleared their way.

The Mooney was high, so the instructor began a forward slip on final. The airplane floated down the two-mile-long runway until it reached the 5000-foot runway remaining marker and was ready to land. Afterward, the pilot wrote, “Overall, I am proud of the result, and considering the circumstances, it ended in the best possible outcome.” All this happened while there was another emergency in progress involving a helicopter.

The instructor wisely did not force the Mooney to land. Like many airplanes with laminar-flow wings, forcing one onto the ground invites prolonged floating and a loss-of-control accident.

Yak, Yak, Yak

At Kansas City Center, controller Inga was working with a Yak 18T with multiple problems. The pilot was flying it for the first time. Burning fuel at an excessive rate led him to declare a fuel emergency. And he was in IMC.

His planned destination at Dodge City, Kansas, (DDC) was also IMC, with 1/4-mile visibility and an indefinite ceiling of 200 feet. He had 30 minutes of fuel remaining. There was no fuel to go anywhere else.

Fortunately, the pilot was instrument-rated with more than 20,000 hours of experience. ATC began vectoring him for the ILS 14 at DDC.

The pilot needed the shortest legal approach. He even asked to be turned inside the approach gate just outside the FAF. ATC could see he was below the glideslope and having trouble holding altitude. However, he was established on the localizer, so the controller called mileages and relative position to the airport. Radar contact was lost 1.4 miles from the airport, and radio contact soon after that.

Word that the pilot landed safely came from a supervisor on the phone with the airport manager. Said Inga, “That was an enormous relief. I don’t know that I have felt a wash of relief like that in my life, and I hope I don’t need to again because it was something.”

The pilot kept cool despite being in an unfamiliar airplane and showed that he was thinking every moment, cutting corners to save time. He refused to let the glideslope instrument failure rattle him. His clear thinking and ATC cooperation saved his life.

Problem in Pompano

On a clear morning, tower controller Brad worked four aircraft in the pattern at Pompano Beach Airpark in South Florida. One was a familiar Bonanza.

“You sit in the tower for a year or two, and there are no events,” Brad said. “You’re busy with traffic, but it gets to be routine.” It’s a setup for complacency, but Brad was on the job.

He cleared the Bonanza to land, but something was off. “It didn’t look right, so I put the binoculars on.” The Bonanza was in the flare—with the gear up. Brad immediately issued a go-around, and the Bonanza complied.

Re-established in the pattern, the Bonanza pilot realized he had a gear malfunction and manually lowered the gear. This time, he landed safely.

The pilot called the tower afterward to inform Brad that the aircraft had a gear motor issue that caused the malfunction. He said the go-around saved the aircraft.

The airplane owner later presented Brad with a framed certificate and wrote, “Brad’s actions prevented damage to our aircraft, runway closure, and all the other unpleasant events that follow an aviation incident.”

Try this memory jog, “Green over the green,” meaning three green lights as you approach the grass. It’s corny, but it works.

ATC and You

ATC’s charter is service to the pilot community. They’re eager to help and are only a radio call away.