Capstone, the first large-scale ADSB prototype, was deployed in Alaska in 1999 because Alaska had (and still has) the highest of any state’s aviation accident rate. Despite this challenging environment, by 2006, Capstoneequipped aircraft demonstrated a 47 per cent decline in accident rate compared to non-equipped aircraft in southwest Alaska.

That same year, the FAA integrated Capstone into the national ADS-B program. In 2007, the FAA published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for ADSB Out. After discussion and review, the FAA issued its Final Rule in 2010.

Making the Case

The FAA built its ADS-B business case assuming in part that it could divest 100-plus secondary (transponderbased) radar systems to save money and reallocate it elsewhere in the National Airspace System (NAS) once ADS-B was up and running.

The economics appear compelling. The FAA can save about $400 million through 2035, or about $28M per year in costs associated with operating, maintaining, and sustaining radar systems where there are multiple layers of surveillance and overlapping coverage. By surgically divesting some radars, the FAA can redirect resources to support remaining radars and continue to invest in advanced surveillance technologies for the future.

Over 750 ground-based radar systems form the NAS surveillance backbone. Of these, about 320 radars are used for en-route ARTCCs and are not subject to divestiture. Of the remaining 430 terminal radars, the Radar Divestiture Program plans to divest about 14 per cent or 60 radars between fiscal years 2020-2025. The program must continue through 2035 to realize the projected $400M savings. That leaves 2025-2035 or ten years to divest 40 more radars. It seems probable the FAA will meet or even exceed its goal, though all remain online at this writing.

Not That Easy

The notion that the FAA could pull the plug on 100 ill-fated radars is simplistic. In-depth analysis is required to preserve safety. Moreover, “100-plus” suggests a number less likely a research product and more like an optimistic round number needed to make a sale.

The original radar divestiture list resulted from an analysis performed by the FAA’s Surveillance Portfolio Analysis (SPA) working group in 2017. The group consisted of the FAA, NATCA (the controllers’ union), and NextGen representatives. They reviewed radar needs in the NAS after implementing ADS-B and came up with just 18 candidate sites for full removal.

In 2018, NATCA did its own analysis. One of its first concerns was the FAA’s heavy reliance on military radars, which have historically had issues with availability and ground clutter. After considering military radars, ADSB availability, overlapping radar coverage, and more, the number dwindled to seven. Across all terminal radars, a thumbnail estimate identified 15 additional candidates.

Interestingly, the panel concluded that partial removal, divesting only secondary or primary radar while retaining the other, actually resulted in higher risks than complete removal. Divestiture would only be possible if other overlapping radars offered safe coverage. As a result, NATCA pressed to remove overlapping radar sources completely rather than weakening operational capabilities nationwide.

NATCA ultimately concluded there was no one-size-fits-all solution. In some areas, ADS-B is not required, including many Class D airports and some Approach Controls. The final determination needed to be made at the local level to gauge any compromise of coverage accurately.

Preserve Safety

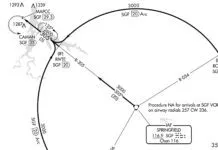

Similar to the 300-odd VORs on the block, reducing the number of radars is like practicing medicine: first, do no harm. There are three steps that protect NAS users from possible harm.

First, the divestiture team will conduct an in-depth engineering study. Can the radar be removed safely? Are the remaining sensors optimized to provide ATC with situational awareness that promotes safe and efficient use of the affected airspace?

Each site will undergo in-depth analysis to answer these questions and more. The team will ferret out the nature of overlapping coverage, radar proximity to other sites, their geometric distribution, and adverse effects on the radar’s line of sight, such as terrain and buildings.

There must be alternative data feeds to the FAA’s automation systems. The team must consider ATC’s operational needs, maintenance, security, and defense requirements. The result of this next level of analysis will launch each site-specific radar divestiture process.

Second, a panel of Safety Risk Management (SRM) experts will analyze candidate radars from a safety perspective. Their task is to evaluate the operational effects, identify hazards, and mitigate risk before a radar is removed from service.

Third, the FAA has long-established standard operating procedures to discontinue and decommission radars properly. Again, these will be adapted to meet site-specific requirements.

Where’s ATC?

As you’d expect, Air Traffic (AT) is a primary stakeholder and deeply involved in the radar divestiture process. FAA headquarters AT managers and NATCA are vital partners to help guide,plan and execute the program. Beyond headquarters, regional AT groups will be included to ensure their interests are addressed.

As envisioned, local AT representatives will be central during site implementation. Local AT staff members are natural subject matter experts because they possess full site operational information and data. They are uniquely qualified to conduct side-by-side ATC display comparisons to evaluate sensor performance. They will also participate in the local Safety Risk Management (SRM) panel.

ATC operations are expected to reap the benefits of new surveillance technology by streamlining the FAA’s radar infrastructure to increase efficiency and optimize ATC services. Any proposed change to operations will be addressed and managed. NATCA will be directly involved to assure their operational interests and concerns are heard. Each radar is a one-off special, tuned to meet local needs. The FAA will work with local NATCA representatives to review SOPs, contingency plans, and any other pertinent operational data to assure that site-specific nuances are not lost in the shuffle.

Divestiture is evolutionary. The FAA must continue to make investments to sustain and replace radars as they age out. Divestiture is not a oneshot deal. As new surveillance technologies emerge, the FAA must continue to assess overlapping surveillance coverage and periodically resize the network to minimize ownership costs.

Downrange

The radar divestiture team does not expect to change maintenance practices or certification of remaining radars. FAA Technical Operations and the technicians’ union, Professional Aviation Safety Specialists (PASS), will help assure that Operations and Maintenance concerns are resolved in the same manner as with NATCA.

When a radar is divested, the divestiture team works out a site-specific disposition developed by relevant stakeholders. Once decommissioned, the assets are expected to be used to serve other surveillance services needs elsewhere.

The Radar Divestiture team picked up where the Surveillance Portfolio Analysis group left off. They share their work with the many stakeholders and dig deep into candidate radars’ qualifications to find all the factors worthy of consideration before pulling the plug. The first need is always safety. The second is to meet the needs of controllers and pilots.

It took the FAA five years (FY2016- 2020) to discontinue just 82 VORs. Divesting radars will be more complicated. Still, the FAA is committed to issuing that reassuring “Radar contact” when you need it.

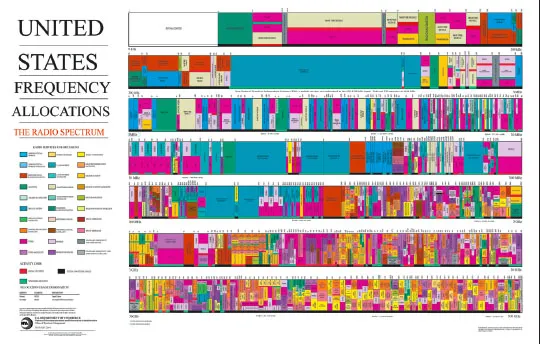

Demand for radio spectrum space far outstrips spectrum available. To see how crammed it is, see the Frequency Allocation Rainbow, where each color represents a range of frequencies allocated to a particular radio service.

The Spectrum Efficient National Surveillance Radar (SENSR) program was chartered to relocate portions of the spectrum occupied by FAA long range radars to another range of frequencies. The government would then auction the space freed to wireless broadband agencies and use the proceeds to replace aging surveillance systems in the National Airspace System.

To this end, Congress passed the Spectrum Pipeline Act of 2015. It mandates federal agencies to free 30 MHz of spectrum below 3.0 GHz for auction by 2024. The auction proceeds would pay for 110 percent of the spectrum sharing cost and allocate $500M for research, development, and planning. The auction will raise billions from wireless companies.

The FAA, DoD, and DHS are looking at the feasibility of making 50 MHz available between 1300 and 1350 MHz. The frequency range of FAA long-range en route radars falls within 1215-1390 MHz. Donating that bandwidth for shared federal and non-federal use would force the FAA to find an alternative frequency range to provide long-range radar surveillance.

In August 2020, the SENSR program was directed to perform a study to assess the practicality of retuning existing long-range ARSR-4 and CARSR radars in the short term out of the 1300-1350 MHz to a new frequency range yet undetermined. Those that could not be retuned would be replaced with new radars within the orange L-band using monies derived from auction proceeds.

New radars seem like a good thing for aviation, but grandiose government plans have a way of getting stuck, derailed, or diverted. Study results are expected in the near future. We’ll be watching closely.

Everyone outside of Alaska loves to promote ADSB in Alaska and Capstone. Been a GA part 91 Alaskan pilot since mid seventies . Today in Alaska ADSB in and out will point out some of the aircraft some of the time! Not to be confused with all the aircraft all the time! Radar up here has more voids the Swiss cheese. Hence 34 fatalities in 2019. I have ADSB in and out in my plane.

Jim, thanks for your comment.

~Fred Simonds