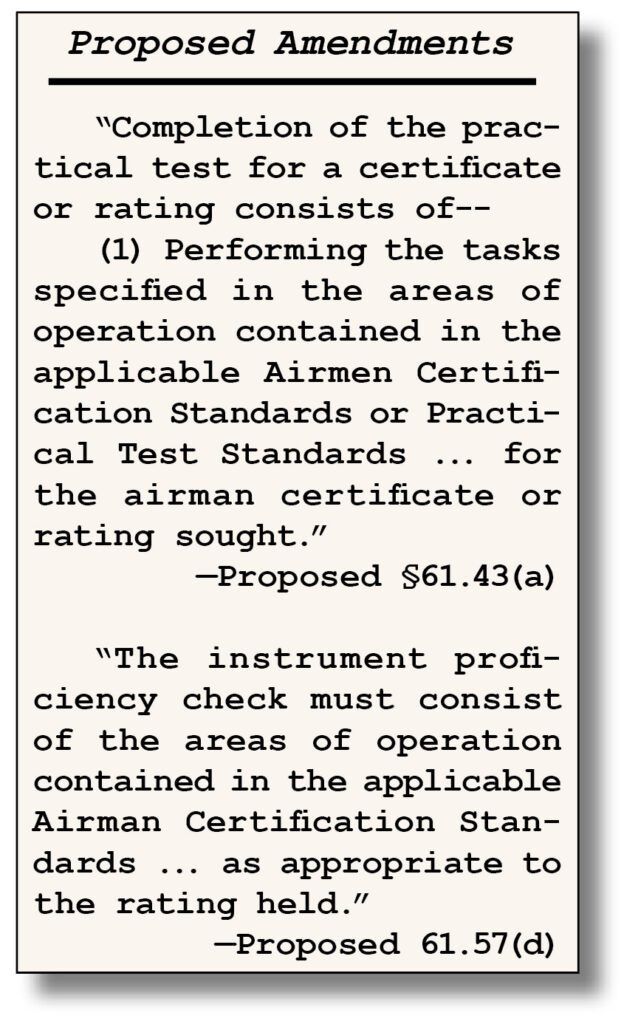

Back in December 2022, the FAA published a Notice of Proposed Rule Making to incorporate the Airman Certification Standards (ACS) into Part 61 of the FAA regulations appearing in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Related documents include the various Airman Certification and Practical Test Standards. Some of the test standards are identical to what we have now. Others are in draft form with revisions, mostly minor.

Back in December 2022, the FAA published a Notice of Proposed Rule Making to incorporate the Airman Certification Standards (ACS) into Part 61 of the FAA regulations appearing in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Related documents include the various Airman Certification and Practical Test Standards. Some of the test standards are identical to what we have now. Others are in draft form with revisions, mostly minor.

One group with a more significant change for instrument trainees and rated pilots alike is the draft Instrument ACS. It brings an important change affecting both the instrument checkride and the IPC. We will focus on the draft Instrument-Airplane ACS but there are similar changes in the new draft Instrument-Helicopter ACS.

Isn’t the ACS Regulatory?

The FAA has always treated the Practical Test/Airman Certification Standards as at least quasi-regulatory. Even if viewed as just part of the deal between the FAA and its Designated Pilot Examiners, if DPEs must use it for practical tests, it’s effectively a requirement.

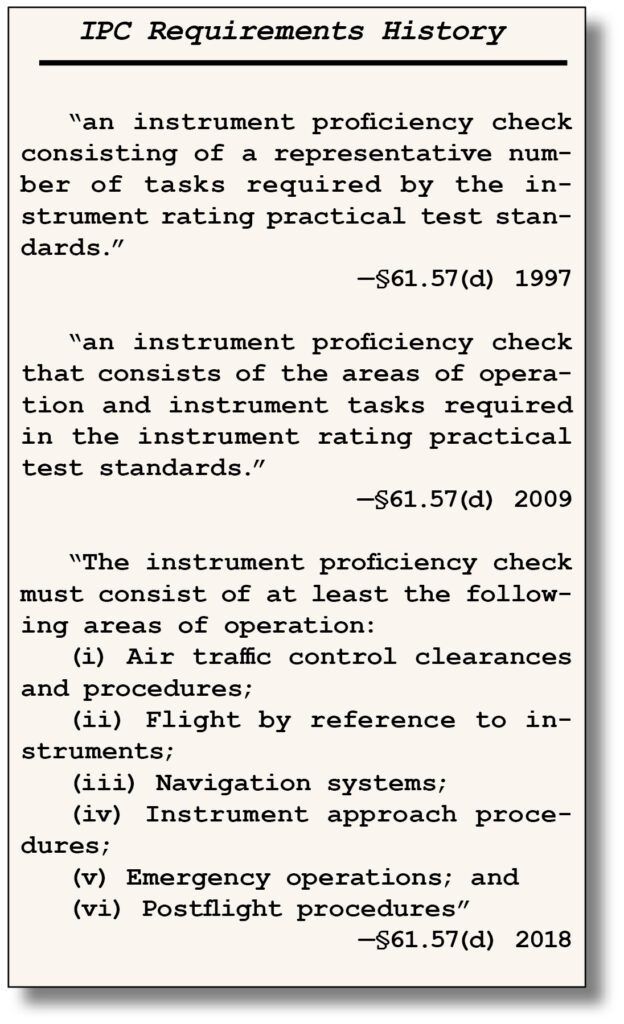

But the relationship between the Test Standards and the IPC has been more muddied. At one time, the only regulatory directive for an IPC in §61.57(d) was to look at “a representative number of tasks” from the PTS. The proficiency check table already existed but folks argued that CFIs were not required to follow it. In 2010 the Department of Transportation (DOT) agreed.

In FAA v. Recurrent Training Center, Inc., the FAA brought a civil penalty action against a company that was giving instrument proficiency checks in flight training devices. The devices were not certified for circling approaches or landings; those PC Table tasks were not performed. The civil penalty action claimed that the organization was improperly endorsing IPCs.

The DOT (which hears appeals from FAA civil penalties) decided in favor of Recurrent Training Center. The PTS, said the DOT Administrative Law Judge, “does not have the force of law.” “It was not adopted with the protections of notice-and-comment rulemaking under the Administrative Procedure Act.” In short, the PTS, according to the DOT, is not regulatory.

The events in the case took place during 2008. In 2009, the FAA amended §61.57(d) to require adherence to the Test Standards. Coincidence? Perhaps.

Fast forward to 2018. The FAA adopted a number of welcome amendments. (See “Finally: Revised Regs” in the September 2018 IFR). By that time, the PTS had morphed into the ACS. Instead of simply changing the 2009 language from PTS to ACS, the FAA dropped the direct reference entirely, replacing it with a statement that the IPC must include certain specified “areas of operation.” The Final Rule says this did not represent a change; Recurrent Training Center provides support that it did. (I do not recommend being a test case).

The FAA does not cite Recurrent Training Center in the Proposed Rule. But it does recognize the problem. “Because of the regulatory nature that the PTSs and ACSs are purposed for, through this proposed rulemaking, the FAA is proposing to [incorporate] the ACSs and PTSs into Parts 61, 63, and 65 so that the standards carry the full force and effect of regulation.”

Instrument ACS

The Proposed Rule includes drafts of planned modifications to a number of Test Standards, including the Instrument ACS.

In previous issues of IFR, we discussed the retraction of the Chief Counsel’s very restrictive reading of the “different kinds of approaches” language in the §61.65 dual cross-country requirement for the instrument rating (“Which Three Approaches?” September 2022 IFR) and Flight Standards’ very practical follow-up guidance in ¶5-434 of FAA Order 8900.1 (“These Three Approaches,” February 2023 IFR). The Chief Counsel’s restrictive “three different kinds of navigation systems” (VOR vs GPS vs LOC) became Flight Standards’ three different approaches “defined by the various lines of minima found on an approach plate” (LPV vs LNAV or ILS vs LOC).

The problem for the Instrument ACS is the same. The ACS currently requires—for the checkride and the IPC—one precision approach and two nonprecision approaches. The single precision approach can be either an ILS or an RNAV approach with LPV minimums below 300 feet AGL. But the nonprecision approaches are more restrictive. The two nonprecision approaches must use “at least two different types of navigational aids.” That means at least one non-precision approach must use a VOR, NDB, localizer or localizer-like (such as LDA or SDF) ground-based navaid.

We are in a world where VORs are being reduced to a “Minimal Operational Network” and approaches considered to be redundant (mostly VOR and NDB) are being decommissioned. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to find a viable ground-based nonprecision approach. If we’re lucky, there’s something close, but often scarcity requires work-arounds.

We pretend there’s a NOTAM that the local ILS glideslope is unreliable, ignore it, and fly to LOC minimums. We fly VOR and LOC approaches that require DME using GPS in lieu of DME. It’s perfectly okay to do that for training and currency, but many, perhaps most of us, would not fly a LOC or VOR approach in real life unless there was a GPS outage. And in that case, we would not be able to fly VOR/DME or LOC/DME because we don’t have “real” DME in our modern aircraft.

Like Flight Standard’s handling of “different kinds of approaches,” the draft Instrument ACS takes the reality of today’s modern avionics into consideration.

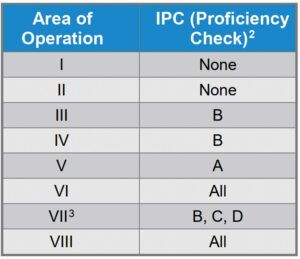

There are no planned changes to the IPC table itself. The headings using the word “required” is new, but the list and the underlying tasks are the same. The big change is in the new Appendix that discusses the equipment requirements for Area of Operation IV, “Instrument Approach Procedures.” That’s Appendix 7 in the 2018 Instrument ACS and Appendix 3 in the draft ACS.

Precision vs. Nonprecision

The current instrument ACS differentiates between precision and nonprecision approaches in two ways. Equipment and altitude. Using ground-based navigation equipment, a precision approach under the 2018 ACS is one that utilizes an ILS or GLS (GBAS, formerly LAAS) glideslope. Nonprecision approaches are those that don’t, such as VOR or localizer.

It gets more complicated when we look at RNAV. Under the 2018 ACS, an RNAV approach to LNAV or LNAV/VNAV minimums is nonprecision. But the status of an RNAV approach to WAAS glidepath-enabled LPV minimums depends on the decision height—the DA’s height above touchdown. It counts as a nonprecision approach “as long as the LPV DA is greater than 300 feet HAT.” It counts as a precision approach “if the LPV DA is equal to or less than 300 feet HAT.”

The draft ACS does away with those complex gyrations in favor of a simple distinction. A precision approach for instrument checkride and IPC purposes is, under the draft ACS, a “standard instrument approach procedure to a published decision altitude using provided approved vertical guidance.” In contrast, a nonprecision approach is “to a published minimum descent altitude without approved vertical guidance.”

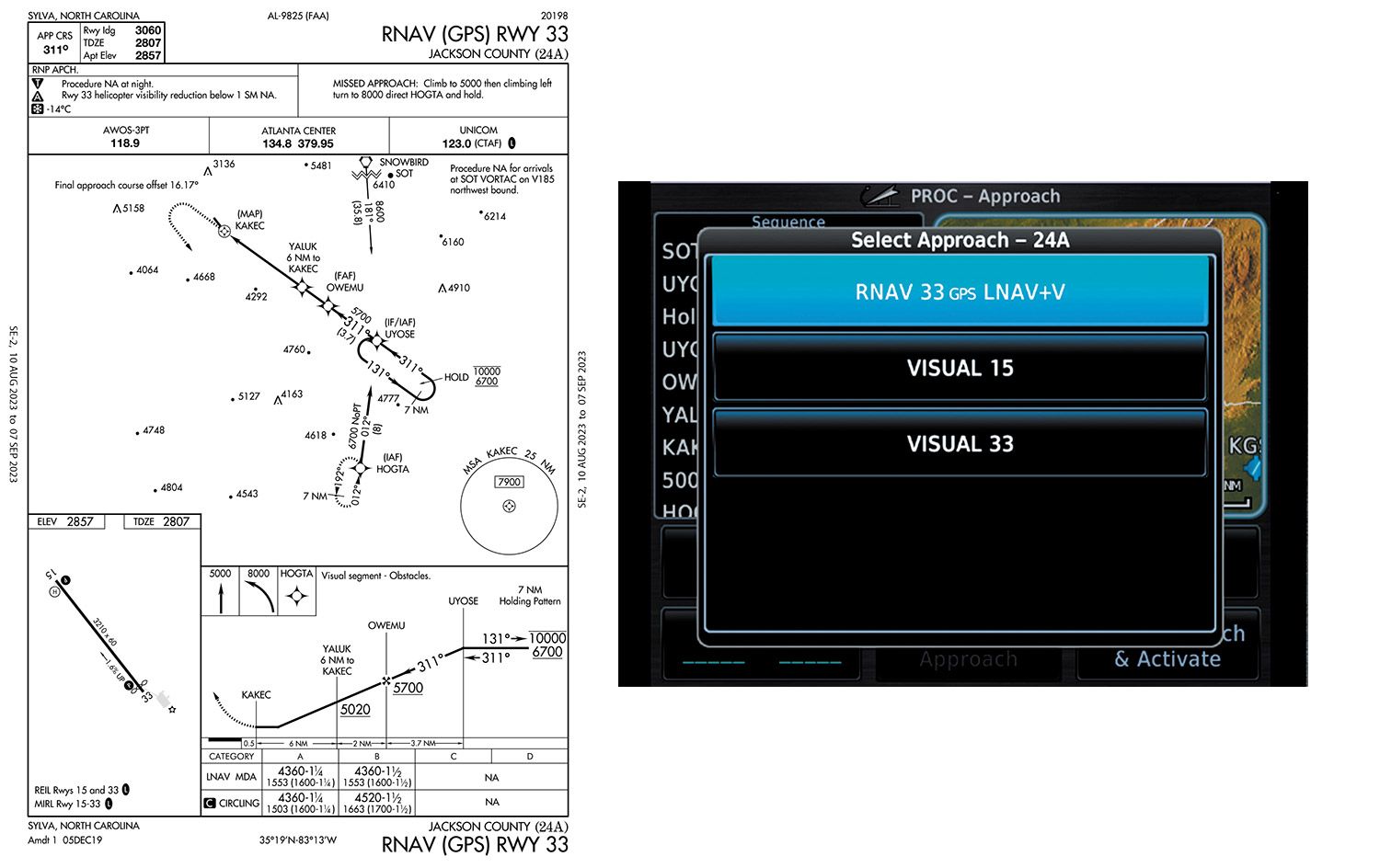

Read “approved” as “official” vertical guidance that is part of the approach that was created using TERPS standards, to published ILS, GLS, LPV or LNAV/VNAV minimums. Anticipating the obvious next question, “The applicant may use navigation systems that display advisory vertical guidance during nonprecision approach operations, if available.” The RNAV 33 into Jackson County, North Carolina (24A), which has only LNAV minimums, does not morph into a precision approach just because your navigator annunciates LNAV+V and provides an unofficial advisory glidepath.

Happy Day!

It’s difficult to predict what making the ACS regulatory will do. Practically speaking, the net change may be zero. Except for unusual cases like Recurrent Training Center and periodic arguments by CFIIs along the same lines, the ACS has been treated as checkride and IPC gospel.

From a regulatory standpoint, while requiring the FAA to follow Administrative Procedures Act notice and comment requirements may add a layer of protection to unwelcome ACS changes, it might also significantly slow the process for adopting welcome ones.

The FAA tells us in the Proposed Rule, “there are no major substantive changes proposed to the testing standards that are already in use.” That may be true for the Areas of Operations and Tasks (although it’s hard to describe changes from PTS to ACS methodology as insignificant). However, if the drafted changes to the Instrument ACS Appendices becomes final, it will be a welcome more accurate reflection of the tasks that apply to the real world of instrument flight.

The Proposed Rule and the affected testing standards may be viewed at https://www.regulations.gov/search?filter=FAA-2022-1463. The comment period ended February 23, 2023. As of the time of this article, that has not been extended and comments were minimal.

Mark Kolber is a (retired) aviation lawyer and active CFII who says that the more imprecise the approach, the more precision we need to fly it.