Separating airplanes is numero uno among an air traffic controller’s many duties, but it’s really only the tip of the iceberg. On a day-to-day basis, we’re purveyors of information, passing it back and forth between parties who can make use of it.

Weather and NOTAMs are a huge percentage of the mountains of data controllers process daily, and a significant chunk of that comes from pilot reports. Some pilots wonder how the information they share gets processed by ATC. As one IFR reader expressed: “It appears that most reports of icing/tops/bases that are reported to ATC never make it into the PIREP system.”

The underlying mission of air traffic control—aviation safety— provides a strong incentive for controllers to quickly file relevant weather or equipment reports through one of several avenues. The unfortunate truth is that high traffic or other workload may dictate a shift in priorities.

Taking Notes

Controllers must solicit PIREPs under certain conditions, such as when the ceiling is at or below 5000 feet, or visibility drops to or below five miles. Hazardous weather phenomena, including thunderstorms, wind shear, moderate or greater turbulence, icing at or over light levels, and volcanic ash, will also trigger PIREP requests from ATC. If you’re encountering any of those factors, let ATC know so they can spread the word.

When you report something, a controller may just jot it down on a note pad, or grab a copy of FAA form 7110-2. The latter is a simple form that lays out all the possible elements of a PIREP. ATC facilities usually have full pads of them lying around.

Section 2-6-3 (d) of FAA Order 7110.65 (the ATC rulebook) states: “Relay pertinent PIREP information to concerned aircraft in a timely manner…Relay all operationally significant PIREPs to…” then comes a list including a facility weather coordinator, other sectors or ATC positions, Flight Service, and other concerned facilities.

What constitutes “operationally significant” is a judgment call as to how much a report differs from the known weather conditions and how greatly it could affect flight safety. For instance, if a METAR is reporting the ceiling is overcast at 4500 feet, and you report breaking out at 4600 feet, it’s probably not worth filing. However, if you report moderate turbulence and light rime icing, that’s prime PIREP material right there.

Raising the Alarm

Of course, just writing it down or having the controller advise aircraft directly in his area doesn’t do anyone outside that ATC facility much good. That PIREP needs to be disseminated throughout the National Airspace System so that every affected pilot can access it.

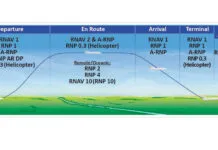

Traditionally, either a controller, ATC supervisor, or another specialist would call the relevant Flight Service Station directly using an internal voice landline and pass on the PIREP information verbally. Recent years have seen a hard shift towards electronic submission, with the particulars varying between Centers and Terminal (both Tower and Approach) facilities.

Centers have hundreds of controllers, dozens of radar sectors, and the internal personnel structure to support them, including a dedicated Center Weather Service Unit (CWSU) staffed by meteorologists. A Center controller can enter a PIREP into a specialized computer console next to the ‘scope, sending it to the weather folks. The CWSU can take urgent PIREPs—like icing and turbulence —and transmit them to relevant terminal facilities under their center’s jurisdiction. These print out on the same printer used for flight plans, so they’re readily available.

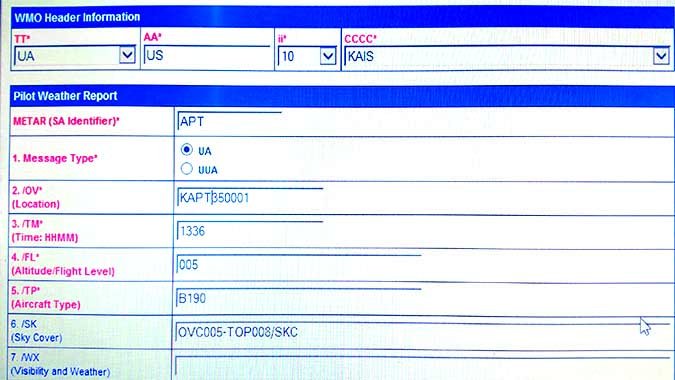

In the terminal environment, controllers are now using an online system called the Aeronautical Information System Replacement. The AISR PIREP reporting form follows the familiar PIREP format. We usually keep the web page up on the tower and radar room computers so we can quickly type in a report. After we click “Submit,” it goes through some behind-the-scenes processing and formatting before becoming available to the end users via Flight Service and other avenues.

Trouble in Paradise

Weather is only one of the things pilots can report. Lighting systems, radios, navigational aids like localizers and VORs are all subject to wearing out or just breaking. Even runways themselves can have problems over time. We have to know about it before we can send someone out to fix it.

We don’t always need the PIREP. ATC facilities have monitoring panels for key equipment, such as VORs, NDBs, localizers, and glide slopes, which trigger alarms or warning lights when the gear fails. Many of these things are also monitored off-site by regional command centers, so even if a tower is closed, somebody’s aware of the problem.

Some issues controllers can’t discover without your help. This is especially true with lighting. An airport may have thousands of individual lights and dozens of specialized lighting systems scattered around many square miles of property. Not all are visible from the tower.

Take the PAPIs. A control tower is typically situated midfield, while the PAPIs are not only at the runway ends, but (hopefully) facing away from midfield. We have no idea there’s a problem until a pilot or airport inspection vehicle says something. The same goes for MALSRs, REILs, and other lighting arrays that are located on or beyond the runway threshold.

Nuanced problems are also hard for ATC to detect. Occasionally, one of our ILS systems may start fluctuating, but not enough to trigger our monitor panel’s alarm. Or, the radials of a certain VOR may lose signal. If something feels “off” in the way your needles are acting—or you’re unable to pick up a navaid’s signal at all—let ATC know. The same goes for voice radios. Can’t hear ATC too well? Advise us so we bring our backups online and investigate further.

For navigational aids and radios, we typically get another aircraft to check it out before we start making phone calls. It’s not a trust issue; we just need to ensure the fault actually lies with our gear, and not the aircraft’s onboard avionics. Usually, the initial pilot’s report is accurate and the suspect equipment really is down, but not always. If we get a cross-check in time, we may be able to advise the first reporting pilot, so he can get his aircraft checked out.

We Just Work Here

Presuming it’s broken, the next question is: Who do we call? When you look out at an airport through your windshield, the runways, taxiways, navaids, markings, lights, and signs may appear to be parts of one massive whole. What you don’t see are the complex walls of jurisdictions and bureaucracy dividing each element. While all airports are unique, it’s a fact that every single one of those things belongs to somebody when it comes to repair.

Let’s look at one of our runways and its associated systems. If a runway edge light or hold short sign burns out, the city-run Airport Operation Center (AOC) maintenance crews handle it. However, the REILs, MALSR, RVR sensors, and PAPIs on the exact same runway are the responsibility of FAA Technical Operations (TechOps). The ASOS weather sensor package next to runway belongs to the National Weather Service (NWS).

As an aside, we deal with this inside our own control tower building: structure, plumbing, electrical, rotating beacon, and other environmental stuff is AOC’s; the ATC-related operational gear (radios, radar ‘scopes, phone lines, light guns) are TechOps territory, and the NWS owns the weather terminal.

When something’s broken, we’ll first note it in our facility log under an equipment entry. These “E” entries are automatically sent to the TechOps folks. We’ll also call the appropriate overseeing authority, whether it’s Airport Ops, FAA TechOps, National Weather Service, or someone else. Whoever we call should file any applicable NOTAMs.

Keep Your Eyes on the Ball

The multiple steps involved in filing NOTAMs and PIREPs can steal time from a controller’s main purpose of separating aircraft. From their first transmission as a trainee, controllers have the term “priority of duty” bashed into their head. Allowing two aircraft to get too close because you were distracted by a PIREP or a NOTAM is not an option.

This brings us back to the reader question. The less busy the controller is, and the more people available in the radar room or the tower cab, the more likely the PIREP will get filed. Overloaded controllers simply don’t have the time to take their eyes off their traffic, but should be warning the pilots in their airspace about reported issues.

Larger facilities may have supervisory staff on hand to process the information and make the appropriate calls. If I get a PIREP or a broken equipment report, I can call my sup over and tell him what’s up without having to step away from my traffic. Heck, one time we tasked our facility manager with some necessary coordination for an equipment outage. We needed the help and he just happened to be in the radar room, so we put him to work! The important thing is getting the info out there.

What if there’s no dedicated sup on deck? That’s often the case with mid-level and smaller facilities that can’t justify a full-time supervisory staff. These places often run with combined positions. A tower cab could have one controller on Tower, and another working Ground, Clearance, and Controller in Charge (CIC) all together. CIC functions as an ad hoc supervisor when there’s no supervisor in the operation. On top of issuing clearances and taxi instrucLarger facilities may have supervisory staff on hand to process the information and make the appropriate calls. If I get a PIREP or a broken equipment report, I can call my sup over and tell him what’s up without having to step away from my traffic. Heck, one time we tasked our facility manager with some necessary coordination for an equipment outage. We needed the help and he just happened to be in the radar room, so we put him to work! The important thing is getting the info out there.

What if there’s no dedicated sup on deck? That’s often the case with mid-level and smaller facilities that can’t justify a full-time supervisory staff. These places often run with combined positions. A tower cab could have one controller on Tower, and another working Ground, Clearance, and Controller in Charge (CIC) all together. CIC functions as an ad hoc supervisor when there’s no supervisor in the operation. On top of issuing clearances and taxi instructions, the Ground/CD/CIC is responsible for filing PIREPs and NOTAMs. During a heavy departure push, the report may get sidelined.

Ideally, there would always be time and manpower for filing every PIREP or NOTAM instantly. Unfortunately, both those things are limited. When the traffic builds and resources get tight, that timeliness may go right out the tower window.

See Something? Say Something.

Air traffic controllers rely on pilots to spots things that are out of the ordinary, and that doesn’t just mean weather or busted equipment. If you see something that could be a physical threat to an aircraft, please speak up.

One day, I had a Piper Cherokee inbound to land on one runway. Number two to the airport was an Airbus A320 airliner landing on an intersecting, crossing runway. The Cherokee landed, swerved a bit, but corrected back towards the centerline. He stopped in the intersection of both runways.

The Cherokee seemed disoriented and wasn’t moving. Had he kept rolling through the intersection, the spacing would have been a no-brainer. Now, however, I had no choice but to send the Airbus around. That accomplished, I asked the Cherokee if he needed assistance. He said, “No.” Ground taxied him back to the ramp without—so we thought—any further incident.

This is where one pilot’s keen eye came into play. Another aircraft was waiting to cross the runway on which the Cherokee had just landed. Its pilot told Ground, “Hey, I think that Cherokee just knocked over a runway light.”

Ground and I snatched up our binoculars. Crap. The last runway light prior to the intersecting runway was lying on its side. It wasn’t obvious unless you knew exactly where to look. Who knew how much glass or metal debris was scattered across both runways, just waiting to get sucked into an engine and cause Foreign Object Damage, commonly just called FOD.

Direct FOD damage isn’t the only concern. It’s the domino effect. A Concorde was brought down in July 2000 by a 17-inch by 1.3-inch titanium strip a 20th of an inch thick, dropped on the runway by a preceding aircraft. The FOD burst the supersonic airliner’s tire on takeoff, flinging debris at 300+mph into the left wing. The shockwave ruptured a fuel tank, triggering a massive fire, a double engine failure, and a horrific crash into a hotel claiming 113 lives.

I called the Airport Operations Center, who closed both runways, got a city maintenance crew out there to sweep for debris, and cleaned everything up. Meanwhile, I called the FBO where the Cherokee parked, so the pilot could check his plane for damage and give us a call so we could start the required incident paperwork. All this time, our radar guys were holding arrivals out, and we were holding our departures short. Not too long thereafter, we were back in business.

We’ve had many FOD threats spotted by watchful pilots, like metal pilot kneeboards or flight instructor clipboards (probably forgotten on a wing), and aircraft parts like fuel caps and exhaust pipes. If it had not been for watchful pilots, any of those could have caused significant damage to an aircraft, and —worst case scenario—someone may have gotten hurt.

Tarrance Kramer wishes every day was “better than 5000 and five” while working traffic out in the Midwest.