From my base in Santa Barbara, Calif., I often fly north to San Jose (KSJC). At San Jose, GA aircraft operate from Runway 29, parallel and to the west of the two main runways, 30L and 30R for jets. All the runways have straight-out IFR missed-approach procedures.

One night, while I was waiting for release on 29, Southwest 376 (a 737) reported on final and asked, “How close is 376 to the killer bee ahead?” He was referring to a 757 and its reputation for leaving a brutal wake.

Holding short, I imagined a scenario in which I’m on a half-mile final to 29 when the Tower clears a 757 to take off on 30L. What if I had to go around? It’s a perfect recipe for a wake-turbulence encounter—except in IMC.

“Tower, Seven Seven X-ray. You have time for a question?” With permission, I continued: “Would you ever clear a 757 for takeoff if I’m on short final to 29?” It was no surprise to hear: “Affirmative, wake-turbulence avoidance is the pilot’s responsibility. We just don’t clear GA for takeoff for three minutes behind a 757 taking off.”

Into the Maw

Fast-forward to an early morning in June where Southern California is blanketed in low stratus. I was en route to John Wayne Airport (KSNA) from Santa Barbara. I checked in with Approach outside LEMON, the FAF for 19R, at about 7:10 a.m. Weather was 1200 and three.

Approach told me to keep my speed up for a 737 following me. I was handed off to Tower. With three miles to go, Tower advised, “Seven Seven X-ray, a 757 is holding in position, 19R. We’ll release him before you land.”

A few moments later Tower said, “Seven Seven X-ray, the 757 will be departing when you’re one mile.”

“Damn,” I thought. “What now?” I knew I could touch down before the wake, but I know comparatively little about jet blast, which was now looming as a new and big concern.

I had broken out earlier but I still couldn’t see the runway. I hadn’t yet heard the 757 being cleared for take off. As I proceeded down the ILS, I asked, “Is 19L available?” the shorter, parallel GA runway. But just as I released the mic key, I saw the airport from about a one-mile final. The 757 was still in position.

Now I could see 19L. The tower responded, “19L is not available.” I could see why. It was loaded end to end with airliners waiting to take off, common for that time of day, I later discovered. Meanwhile, the DME clicked down.

“United 348, cleared for take-off,” Tower told the jet when I was on about a half mile final.

John Wayne Airport is just north of Newport Beach and residential areas. The 757s fly fully loaded to the East Coast off a short runway and climb at an incredibly steep deck angle for maximum noise abatement—both of which combine to produce maximum wake.

“What a choice,” I thought, “jet blast or wake turbulence!”

“Tower, Seven Seven X-ray is going around,” I said.

“Roger, Seven Seven X-ray proceed south. Are you canceling IFR?” Tower asked.

“Affirmative,” I responded.

South? That would have put me right into the 757’s wake. No way. I began turning east to avoid the fresh 757 wake.

“Seven Seven X-ray, why are you turning?”

“To avoid the wake.”

I turned easterly, over the closed runway. I was more familiar with obstructions there than to the west.

Tower keyed up: “Seven Seven X-ray, if you had proceeded south, we would have turned you west.” I wondered when that would have happened. Not soon enough for me. I saw and reported the 737 traffic that I was to now follow, and landed without a problem.

While driving to my business appointment, I called the Tower and introduced myself. The manager remembered me and was cordial in saying, “Yes, we say south because the coast line here runs due east and west instead of more north and south like most of California. Many pilots mistakenly turn east, so you’re not alone.”

He missed my point. I was not confused about what south meant. Santa Barbara’s coastline runs east-west, too, exactly the same, so I know which way south is. But I didn’t want to “proceed south” because I would have flown into the 757’s wake and could have been a third wake fatality at SNA (see sidebar).

I continued explaining to the controller: “What I’m calling to do is to tell you now what my intentions would be if I get in the same position again. I would declare a missed approach and advise that I’m deviating, flying a heading of 240 degrees to avoid the wake. I’m telling you that now so that you can respond while I’m on the ground and I have time to think about it.”

“240? That puts you southwest. You don’t know what’s there,” he said.

“OK, what would you like me to do, because I won’t ‘proceed south’?”

“Well, then, fly an offset,” he said. Now we were getting somewhere.

“How much?” I asked.

“Over Bravo,” he said.

“Bravo? What’s that?” I asked.

“The parallel taxiway to 19R.”

I was incredulous! Had these guys learned nothing from two wake-turbulence accidents? How could he think that that would avoid the wake, just 100 feet or so to the west of Runway 19R? Jet transports are turned southeast at 1000 feet, but that doesn’t help me when I’m 30 seconds in-trail on a missed, below 1000 feet, sure to pass through the jet’s sinking, diverging, twin wakes.

“If you do that [the Bravo offset], you’ll be OK,” he said.

Now I’m thinking, “Excuse me, but you’re on the ground while I’m in the air, trying to avoid a 757 wake after two fatal crashes. I’ll be the judge of ‘OK,’ thank you.” It was pointless to carry on this cordial discussion.

Miss the Rush

I’ve since looked further into jet blast some. A friend in an Aztec was landing at John Wayne close behind a business jet: “The blast put us in a 45-degree bank 50 feet above the ground for one second,” he said.

“Yes,” a local instructor cautioned, “jet blast creates substantial turbulence briefly. The hot fumes rise rapidly in intense, though short lived, rotors caused as hot air hits the surrounding cold air.” While only anecdotal, I’ve not read anything more sensible than that about avoiding jet blast.

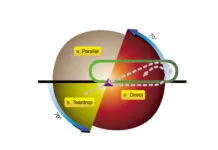

In the past decade, wake accidents appear to have declined. Perhaps awareness and training work. However, make no mistake about it: a missed approach in IMC following a heavy will produce fatalities if a light airplane flies straight out.

Somebody, I think, has done the math at ATC. IMC already bogs down busy airports enough. If GA were given a forward buffer during approach to avoid wake turbulence on a miss, the bog-down would get a lot worse. IFR-operations capacity would take an untenable hit all the time just to avoid a rare, low-probability conflict.

Therefore, ATC will not watch out for you, so be ready. You can and must do it for yourself. This means keeping a mental image of any other aircraft you hear on approach to your destination (or other, nearby fields).

For my problem at John Wayne, I’ve developed a simple, if temporary, solution. On my next flight I sat in my 310 ready to start engines at 6:15 a.m., which, I realized, would put me into John Wayne at about the same time as before. I pulled out my cell phone and called John Wayne Tower.

“Hi, this is Twin Cessna Six One Seven Seven X-ray in Santa Barbara. When’s your rush hour?”

He responded, “From 7:00 to 7:25.”

“You mean it’s over at 7:30.”

“Affirmative.”

That settled it. I opened my laptop and worked until 6:45. Then I got my clearance and launched.

Problem solved … for now.

Frank flies a Cessna T310 mostly around California for business.