Recently I got a request from an instrument student. He needed help fielding the inevitable systems and scenario-based questions about the G1000’s many failure modes.

I authored an article on that topic in 2010 for IFR, but it was insufficient given the depth and breadth of questions he could face. So I added that he should read Max Trescott’s authoritative G1000 Glass Cockpit Handbook.

He asked how many pages it was. His question made me uneasy. Many students want to do the minimum, so I expected pushback when I told him it was about 300 pages. But he responded, “The more, the better! I was hoping it would have lots of pages. I’m an information overload kind of person.” “Me too!” said I. Capping the conversation, he ended, “That’s why we’re aviators!”

Therein lies a mark of an honorable pilot. Principled pilots cannot know enough. We’ve all heard the “license to learn” sermon. Holding a flyable instrument ticket commits us not just to maintain but improve our flight skills and knowledge at every opportunity. Occasionally pilots taking IPCs mutter that they didn’t fully realize the additional obligations of the privilege. Staying up-to-date comes with the territory. Honorable pilots are determined to more than measure up.

Truth and Tail Feathers

At our flight school, I had checked out Reuben in our aircraft and found him to be a solid private pilot. One day he showed up with three passengers he planned to stuff into a 172, but they were all skinny, and his W&B was good.

When he returned, something looked off. The tail tiedown was skewed and bent. There’d been a tailstrike. Reuben denied it. The last pilot to fly the plane said it was perfect, and Reuben did not flag it during his preflight. His flight insurance covered the damage. He had no reason to lie, but lie he did, which was a big mistake.

Ultimately, he admitted failing to anticipate light yoke pressure on landing due to the aft CG. He used normal flare pressure, precipitating the strike.

Tail strikes happen at flight schools, but lying about any incident is unacceptable. The school sent him packing.

Hedging the Hobbs

The same school had many young Commercial Pilot students seeking airline careers. It mandates a 2-hour cross-country flight in a single-engine airplane at night with a straight-line distance more than 100 NM from the original point of departure.

That was too much work for some. The night requirement offered a perfect opportunity to party. Students would fly at night to a nearby non-tower airport, tie the airplanes down, start up the engines, party a few hours, then fly back. No alcohol was involved.

One evening the miscreants got caught. The Chief Instructor called a student meeting and publicly reprimanded the offenders. He emphasized that behaving this way both cons the system and they pay to cheat themselves out of valuable experience, adding that deceit is not how we do things and that an airline employer would severely discipline or fire a dishonest pilot.

Examiners

Some examiners look up random Nnumbers in an applicant’s logbook at the beginning of a checkride. They make sure the applicant can see. If the applicant becomes unnerved, it’s a clear sign there’s been some creative logging.

A school of thought asserts that examiners make up their minds about applicants in the first thirty seconds they meet. They quickly spot sincere, honorable, well-prepared pilots, however nervous, versus the fakers trying to work the system toward a ticket.

The Pale Pilot

Our flying club had a homebuilt, not experimental, airplane for members to rent. Sean did so frequently.

One day after flying it he looked pale as parchment. Shaking, he explained that the elevator froze in the full aft position on downwind. The airplane began climbing rapidly, bleeding off speed and nearing a stall. A muscular guy, Sean shoved the stick forward hard enough to free the elevator, then kept his head long enough to land safely.

A malfunction of the control system is the first required NTSB notification. The owner had the aircraft repaired but never notified the NTSB. “Too much paperwork.” It might have helped prevent other such malfunctions and save lives. If that isn’t dishonorable, what is?

Tom

Tom was a great pilot, but he had no respect for rules. I rode with Tom in the jumpseat of a Rockwell Sabreliner bizjet and can attest that it can be rolled left and right high in the flight levels. No other passengers were aboard.

ATC once asked him to check altitude. He was about 500 feet low. Tom snapped off the Mode C altitude reporting, yanked the Sabreliner to the correct altitude, then switched on Mode C.

Tom loathed the FAA, and it was mutual. Since he owned a flight school, the FAA applied leverage. Inspectors discovered that Tom signed students off for flights they never made. Invoking their emergency authority, the FAA revoked all his certificates, zeroed his thousands of flight hours, and reduced him to a student pilot. He was benched for a year until he could apply to take his ratings all over again. Such is the penalty for dishonoring the system.

IFR Deviations

You’re flying toward a buildup. You need to turn fifteen degrees off your heading to avoid it. Do you ask ATC or deviate just enough to get around? Some pilots, airline types too, simply turn. Many controllers appreciate it because it lowers their workload. Some pilots compromise and ask if ATC is not busy but skip the call if they are.

The Confessor

Our editor, Frank, offers this real-life anecdote.

Frank feels familiar with his GTN navigator, but not as much as he would like. Many pilots share that nagging sense of inadequacy. Folks, forgive yourselves. These boxes are so featurerich it’s practically impossible to know it all, especially their little and often undocumented nuances. Even if you do, you’ll soon forget stuff you don’t use.

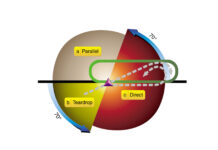

Returning home, ATC told Frank to expect a certain RNAV (GPS) approach. Soon he was cleared direct to the IF/ IAF, which also served as an inbound holding fix, and advised to expect a hold there for preceding traffic.

Frank loaded and activated the approach from that IAF. Anticipating the navigator would command but one turn as a hold-in-lieu, he manually programmed the hold to stay in it until he received further clearance. The GTN defaults to right turns. But he missed the fact that the charted hold was for nonstandard left turns and didn’t catch his error until too late.

Once he hit the fix, the aircraft started turning right. In a flash, he realized why. Certain he was still well within protected airspace, he immediately ‘fessed up: “Entering hold … I goofed, and I’m turning the wrong way. I can fix it now or continue in this hold. What would you like?” The controller pleasantly replied that he had plenty of clearance at his altitude, so the wrongway hold was fine. Once inbound to the holding fix, he again offered to fix it, and she accepted, again very pleasantly.

Looking back, when he first caught his error, he had three options. First, he could and did the honorable thing thrice: Admit the goof, ask what to do, and offer to fix it. Most of us would go this route because it’s the right, safe thing to do.

Second, he could hope she wouldn’t notice and fix it on the way inbound. Third, he could have immediately flown a figure-8 over the holding fix, trying to correct it again before she noticed.

The second two options never occurred to him at the time; confessing the honest mistake and dealing with it was the only responsible/honorable thing to do, and it worked out fine, as it often does. He didn’t even file an ASRS report—he was confident the situation was no harm, no foul. Had he tried to get away with it, though, that could have been harmful and definitely could have caused a foul. ATC snitch software might have flagged it to FAA’s Quality Control, resulting in a call from Flight Standards, maybe months afterward. It still could.

Takeaways

Decisions like the above are clear-cut. Here’s some guidance when you must interpret a regulation, procedure, POH, or the like.

First, respect the physics—the airplane’s gotta fly. Mistreat it sufficiently, and it will bite, guaranteed. Second, consider the rules in the context of your current situation. As PIC you are honor-bound to bend or break any rule to minimize risk. Third, consider your passengers. Set expectations before departure. Include the possibility of returning or landing short of destination. Promise no sudden maneuvers. Last and most challenging: When in doubt, do the right thing.

A fitness instructor I follow likes to say “how you do anything is how you do everything”. If you’ll cheat on something that isn’t a safety issue, who says you won’t on something that is? Our passengers deserve better than that.