The FAA’s plan for RNAV to every runway makes circle-to-land a rarer maneuver these days. There are still times when it’s worth the trouble, even if it takes a bit more forethought.

Circle-to-land gets a bad rap as a dangerous maneuver fit for only the expert or the insane. Then again, maybe that’s a bit deserved. The circle-to-land maneuver is the proverbial “enough rope”: Give it to a pilot who isn’t careful and he’ll hang himself on an unseen tower just when he thinks he’s about to pull off another successful flight.

The most important part of a circling maneuver is forethought. That and execution. The two most important parts of a circling maneuver are forethought and execution … and having a way to go missed. OK, the three most—ah, nevermind.

The real key to surviving your circles is never letting down your guard.

Lazy Circles

I originally titled this section “Visual Circles” but realized I’d get nasty emails saying, “Every circle-to-land is a visual, you bozo.” My point here is that one subset of circle-to-lands are really modified pattern entries where we are flying with pretty good visibility to a different runway than was aligned with the approach.

This could be for any number of reasons: Your position was too high for an easy straight-in, winds favor another runway (or they might in the near future; see sidebar), or the approach wasn’t aligned with any runway to begin with. This last category is less common with IFR GPS, but it still exists.

To put some numbers on this, let’s say that we’re talking about circling in daylight with visibility about twice your circling category. This means we’re talking near-VFR weather.

The big trap on lazy circles is exactly that: Getting lazy. You can see the runway and the landscape immediately around the airport. It’s tempting to go mentally VFR and just fly a downwind, base and final as needed, cut the power and land.

If you break out 1000 feet above the airport or more, that may work out fine. Or it may not. Remember that in lower visibility, the airport may appear further away than it really is. A downwind might be flown too close, leading to a base-to-final overshoot.

The issue compounds if you break out lower than normal pattern altitude and enter a downwind lower than you normally fly. Now the runway seems too close. Many pilots will also reduce power abeam the numbers and start their descent. But if they are 200 feet lower than normal pattern altitude, they stay 200 feet lower than normal through base, and, oops, are really low on final. With only two or three miles visibility, your peripheral cues are hampered and you might not notice until it’s too late.

Before you say, “So long as there’s an approach to the runway I want for landing, I’ll just take that approach and not circle,” let me toss a scenario at you.

Your destination has only an east-west runway. Winds favor landing east and there’s a good LPV approach to Runway 9. There’s also a small, but quite nasty-looking cell throwing lightning about three miles outside the FAF for that approach. Meanwhile, the approach to Runway 27 is benign IMC in light rain with a mile of visibility. Still wanna shoot that RNAV Runway 9 and tangle with the cell just so you can be aligned on breakout?

Appropriate Protection

Job one for the circle-to-land is to know in advance you will, or even might, do the circle. I like to brief a circling minimum whenever I think I might break out high enough for it to be an option. Just like I call out, “1500 to go … 1000 to go,” as I descend, I’ll call out, “Circling,” to myself as I reach the circling minimums. Then I know if it is an option.

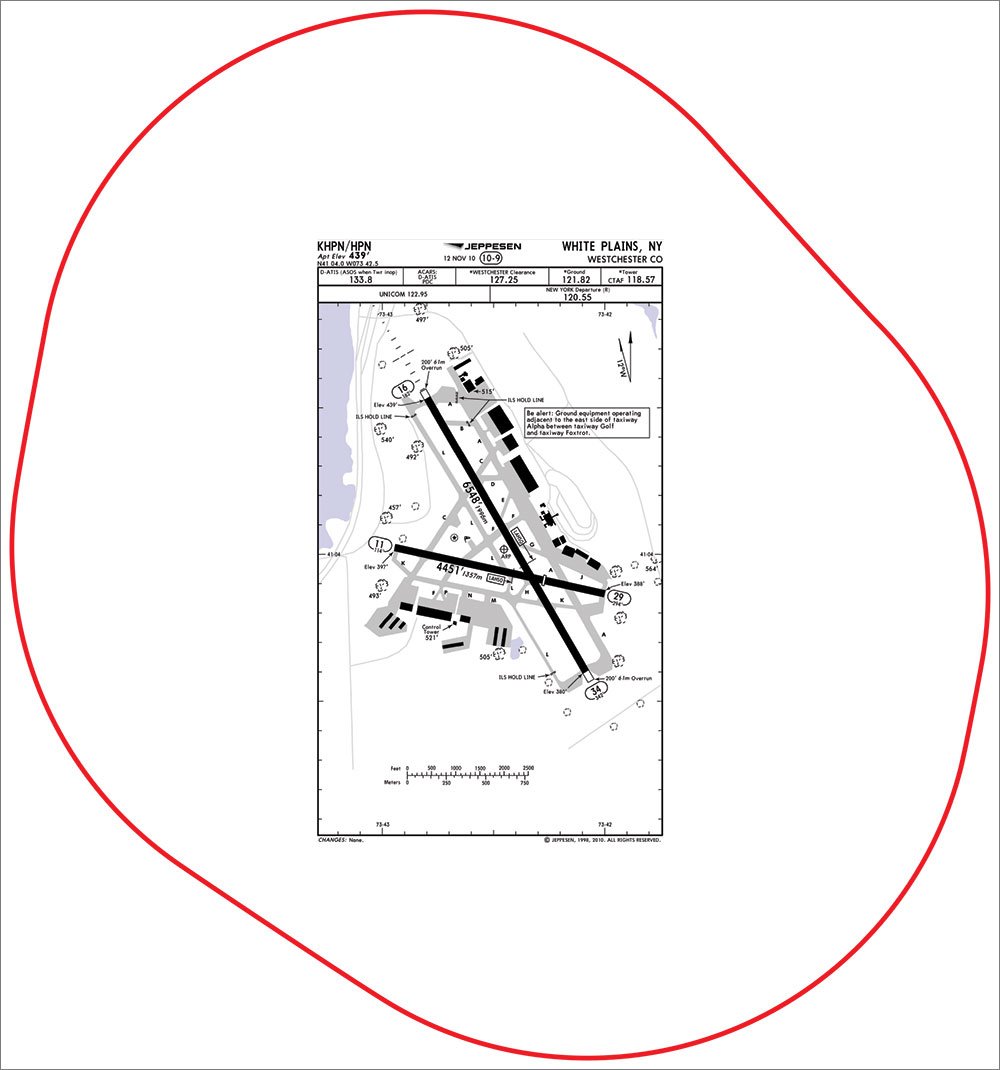

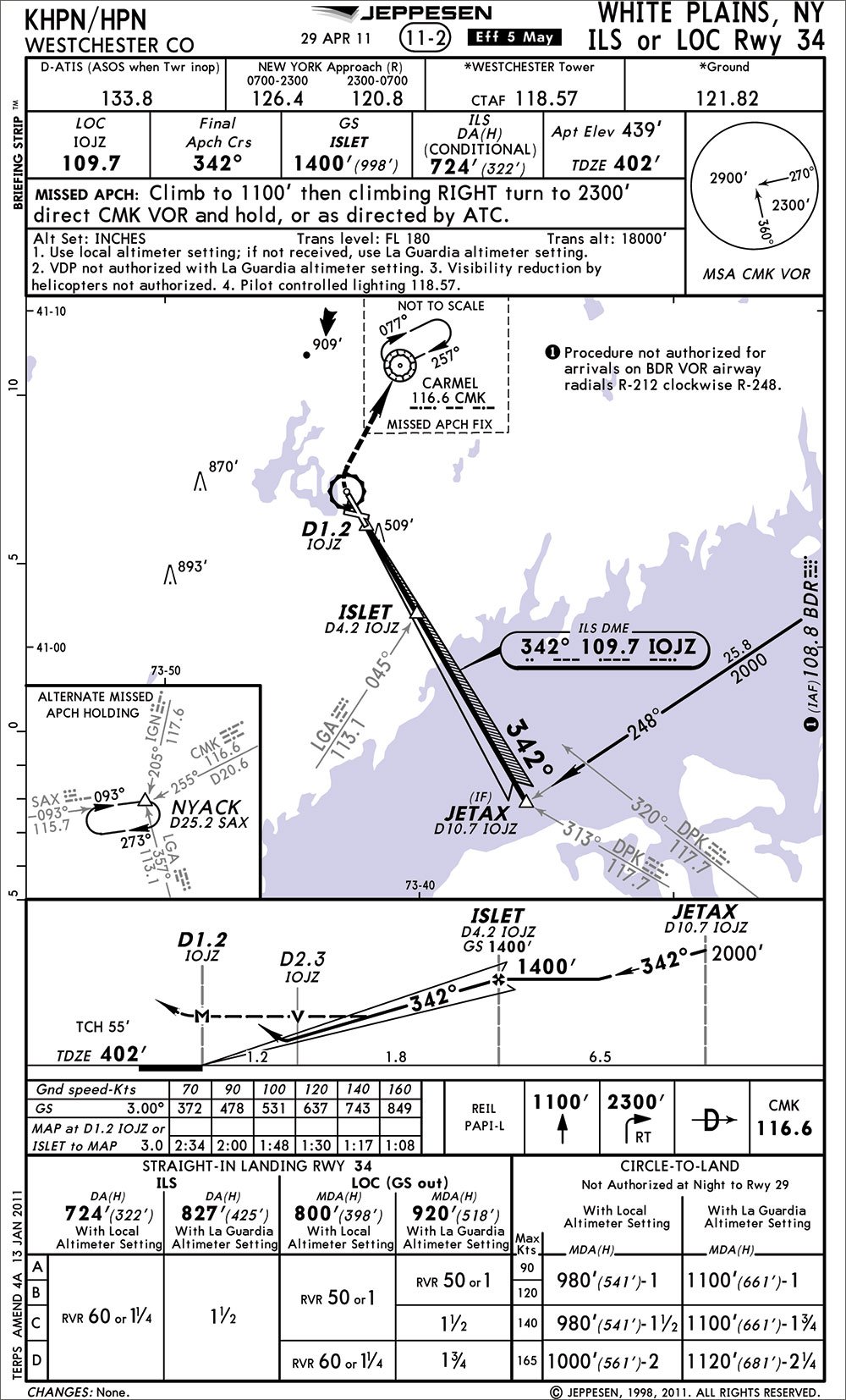

It’s also important to remember how the protected airspace works for circling. The vertical is determined by height above airport (HAA). It can’t be less than 350 feet for Cat A aircraft, 450 feet for Cat B and C, and 550 feet for Cat D and E. In practice, it’s often higher, but you should still think about only having about 300 feet of clearance over an obstacle in your circling area at your circling minimums.

The circling areas are defined by connecting overlapping arcs from the ends of all useable runways. That’s great for the paper-pushers designing an approach, but most of us aren’t as good at guessing distance as we think we are even in reasonably good visibility. The plus is that even the Cat A distance of 1.3 miles is further than most pilots would fly from an airport when maneuvering to land. It can help to know how long the runway is—1.3 miles is about 7800 feet—and use it as a measuring stick.

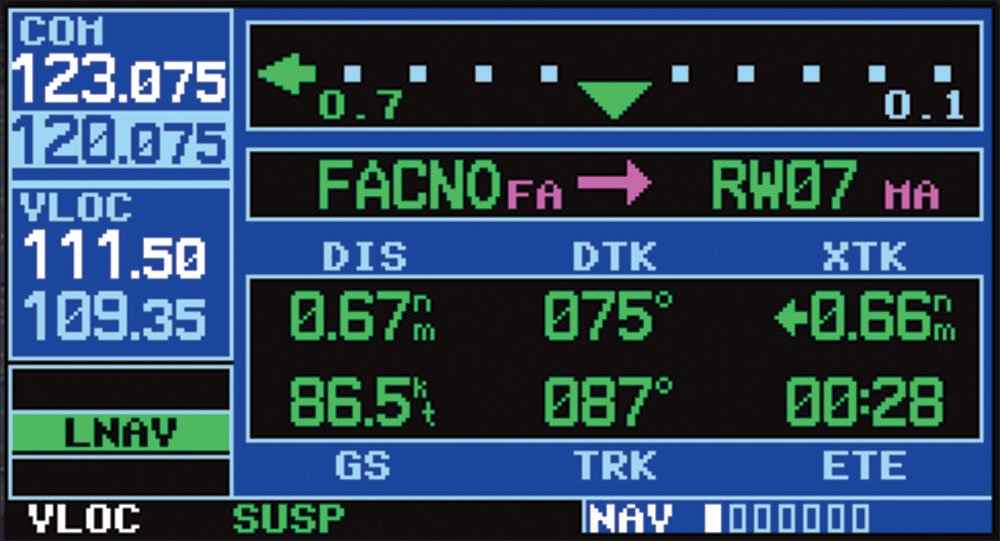

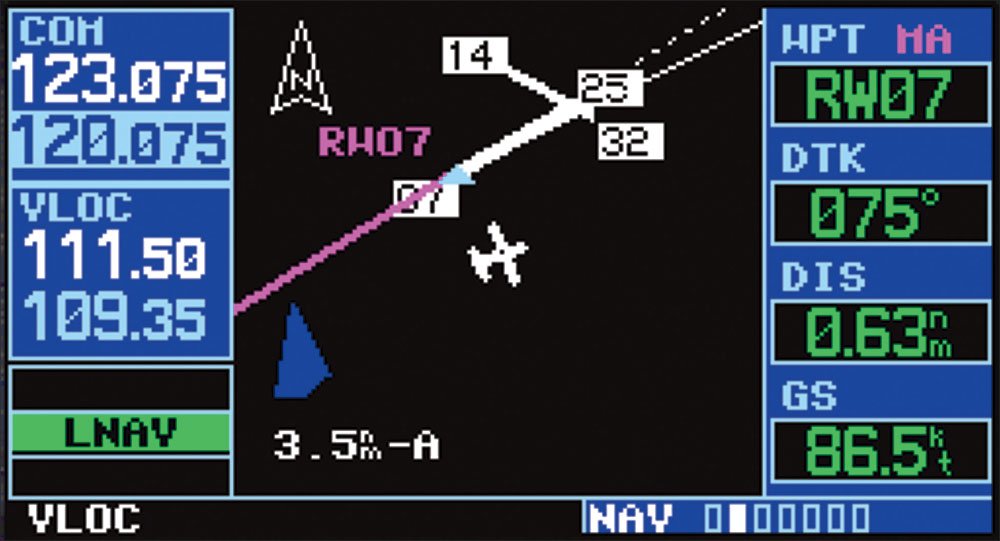

You can use your GPS to measure if you’re prepared. If you had an approach loaded, the MAP is likely at or close to the runway threshold. So long as the GPS stays suspended at the MAP waypoint, you can see your distance to it. Assume you approached Runway 9 and are circling to Runway 27, which is 5400 feet (.89 nm) long. If you reach 2.2 miles from the MAP, you’ve left the protected area for Cat A. There’s also a function called “crosstrack error” on many modern GPS navigators than can show how far left or right you are from the approach course for distances on downwind.

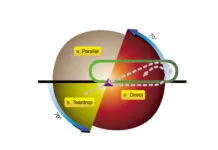

Now that you know how low and how far away you can go, you’ll also want a plan for the path you’ll take to align with the landing runway. Assuming the weather is below VFR minimums, you should own the air and can take any route that makes sense to you. The caveat on this is to double-check in your approach briefing for areas forbidden in the circle. These will appear in the approach notes, such as “Circling NA north of Rwy 9-27.” Often, overflying your landing runway with just enough offset to see the windsock is a good plan. Then you can make a comfortable teardrop back to land.

Your goal should be to fly the simplest path that lets you line up on final—but also the safest. It’s tempting to tuck in close and make a descending turn to final. That’s fine, but if visibility is descent and ceilings permit, consider heading out a bit further and staying above circling minimums until you’re aligned with the final for the landing runway. Remember that you have at least 1.3 miles of protected area from every runway threshold. A longer final gives you a bit of time to reorient and stabilize your approach. You may also get a VASI in view for the entire descent from circling minimums to the threshold, providing extra protection.

A final note on all these “lazy” circles: Don’t get complacent about VFR traffic. Just because you’re thinking IFR doesn’t mean everyone else is. It can be legal to fly a pattern even at night in Class G airspace with only a mile of visibility. And not everyone even bothers with “legal.”

Pucker-Factor Circles

The ante goes way up when visibility isn’t much more than one runway length or when the sun is well on its way to the other side of the earth. I wouldn’t slight anyone who simply refused to circle after dark.

But I’m not one of those people. Again, the circle could be as simple as a pattern entry to a downwind if ceilings and visibility are high enough. I happily fly a normal pattern at night, so why not a circle-to-land from a similar position?

It’s gets trickier when the airport is less than VFR. The core question is: How long can you stay up in the protected area without losing view of the airport?

For low ceilings and darkness, but with otherwise good visibility, a good plan can be flying out far enough that you can do the entire descent from circling minimums to the threshold while still on final. You need some good way to judge the distance you fly outbound, but even a timer can work if you have a good sense of the winds and your groundspeed.

Low visibility and darkness combined is what has really given circle-to-land its bad reputation. There are so many ways this can go bad that it’s worth considering other airports for landing. If you’re still game, the plan is the same, just closer in. My general system is to fly such that I join a downwind for the landing runway, rather than just shooting out at an angle to join base. I maneuver to keep the runway in view, with an offset enough for a 180-degree turn. I fly out from the airport less distance than the reported visibility so when I turn 180 degrees I can descend from circling minimums because I see the runway—or climb toward the center of the airport because I can’t.

The Rip Cord

In a perfect world, we’d never circle unless we were certain we could land. But it’s not a perfect world. Shredded clouds, ground fog, a rain shaft or even a moment of disorientation can make you lose sight of the runway. Yes, the FARs allow for losing sight during normal maneuvers, but you know the difference between “the runway is under my wing” and “the runway is … where?”

You could, theoretically, continue at circling minimums while staying within the protected radial distance and try and find the runway again. Now throw that theory away. If you lose the runway, go missed.

Ah, but go missed where? You probably want to get back on the missed approach course for the runway you flew, but that’s likely behind you somewhere. Here’s what I do, and it’s similar to what you’ll find in the AIM and in many flying texts, FAA and otherwise.

Turn back over the airport as you initiate your climb and continue to climb and turn until you can rejoin the missed approach course for the original approach you briefed. Yes, you could fly a different missed. You could even spiral up and call ATC if you wanted. You can do what you need to do to stay safe. But I think you do best when you renormalize yourself on the original approach and your original plan.

Just understand there is some risk here, and a reason you might want to tailor this thinking for each approach in question. Imagine you have a slight offset to the runway—0.4 miles say—and you lose sight of it. Now you start a climbing turn, but you’re a bit sloppy. Your speed climbs to 105 knots indicated, which at this high-elevation airport is 122 true. Then you only bank to 10 degrees, which is less than standard rate. Your turn radius is 1.2 miles.

Think you’re still inside the protected airspace? Think again. For a 180-degree turn you’ll move twice that radius, or 2.4 miles. That’s even a bit outside the protected area for the Cat D mins. Now, you are climbing, and this is a worst-case kind of scenario, but it’s worth keeping at the top of your concentration that getting back on an established course and altitude as soon as possible is priority one and it’s no time for sloppy flying.

If you know there’s one side of the airport with a mountain and another that’s over the ocean, by all means, turn over the ocean. If you only just began your circle and the bulk of the airport property is still in front of you, just slide back on course and climb without the turn. Are these perfect solutions? No. Are they likely to work without harm to you or your aircraft? Yes. You’re in the hinterlands when you start a missed past the MAP. You do the best you can.

Don’t Write Off Circles

Flying an approach and landing straight-in keeps life simple, sweet and generally safe. Circle-to-land introduces all sorts of messy, subjective decision-making and room for error. It also opens up more options for dealing with weather clogging the approach corridor, landing from a high-and-hot approach, or just saving on taxi time.

The secret to success (and survival) is keeping your wits about you until the point where the wheels stop rolling and the engines tick down.

Winds are Calm? We’d like to circle, please

Back in my formative days, I was riding along with my first instructor on his check-running job around the mountains of central and western Wyoming. We had been flying a Piper Turbo Arrow, dodging scattered cells throughout the afternoon. Cheyenne Regional was our last stop before hoofing it back down to the Denver area.

There was a cell sitting off our left wing as we approached from the west for a straight-in Runway 9. It was heading the same way we were, and the hope was to land and depart Cheyenne before it arrived. Winds had been coming out of the east, gusting a bit, as we approached the airport, probably due to updrafts into the weather we were racing to the field.

On a long final, my instructor called for a wind check. Winds were calm. He requested a downwind to Runway 31. This seemed odd to me, as we were trying to be as quick as possible and were lined up for Runway 9. We landed, tossed the checks in, and started up again. On taxi, the plane got rocked by a gust and the Tower updated the winds: 300 at 22 gusting 28. While we were taxiing out, the storm had begun to rain out.

We departed 31 into a strong wind, turned and headed home. On the way, my instructor explained he knew the gust was coming because the winds had gone calm, but he wasn’t sure when. He had changed runways for landing to ensure he would catch that gust on the nose rather than the tail if it had come earlier. —Jeff Van West

Chet Ludlow lives in Burlington, Vt., and is happy to circle when he deems it safe and the Flight Ops folks won’t fire him for it.