Like the (un?)welcome holiday letter from distant edges of your family, it’s again time to see how the GA family has fared in our annual Safety-Takes-A-Holiday review. The rules are simple: Applicants need only do something stupid in an aircraft that results in financial harm but no loss of life. Qualifying lapses in aeronautical decision making (ADM) can occur in IMC or VMC, day or night, with or without a valid pilot certificate and in anything that flies—legally or not. Boneheaded stunts must be verified by the NTSB, so we’re using calamities from 2011, the most recent with NTSB-posted “probable cause.” No, we don’t make this stuff up.

Art by Ben Bishop

Back To (Stupid) Basics

Pilots still can’t land in crosswinds. These accidents are euphemistically labeled, “loss of directional control,” or “pilot can’t land worth a hoot.” Rebuild shops stay busy replacing gear legs and props from everyday (every stinkin’ day) bad landings that usually don’t cause bodily harm.

Tailwheel pilots are always aggressive on the brakes resulting in numerous prop-curling nose-overs. I’ve personally experienced the glory of flying a 70-year-old Aeronca from a hay field, but one Tennessee accident reminds us that it might be wise to make sure the hay bales have been removed. The Aeronca pilot was cautiously watching a bale on his left but missed his wing approaching a bale on his right. Substantial damage resulted. To the Aeronca, that is, not so much to the hay bales.

Scores of pilots recognized that an approach—or departure—was trending sour but delayed the curative go-around or abort, only to encounter the trees, fences and subdivisions located at runways’ ends. A great many loss-of-directional-control events terminated in nearby ditches, which makes one wonder: Why are runways always built beside ditches?

A Lear 60 crew attempted to taxi from a poorly lit ramp in Indiana when their nosewheel dropped off the pavement. Undeterred, the crew shifted into four-wheel-drive and crossed a grassy knoll toward the taxiway. Anyhow, they tried, until the jet struck a drainage ditch, thoroughly trashing the delta fins beneath its fuselage. Moral: The four-wheel-drive mode in a Lear 60 sucks.

Ag pilots stayed busy in 2011, but such high-stress flying down low resulted in a string of ag-craft clipping power poles, cell towers, the very crops they were treating and, in California, one ag pilot bagged a propane truck and lived to tell the FAA about it.

Speaking of propane, hot air balloons—you know those over-heated gas bags not on AM radio—tangled themselves in treetops, power lines and just about any obstacle available, ejecting passengers like apples from the basket short of the intended landing site. They’re quite popular in June for weddings and graduations, so book early.

Hand-propping is routinely done safely to start antique airplanes. An Arizona pilot even successfully prop-started a Piper Arrow, only to watch it taxi away and drop like Wiley Coyote over a cliff.

Tail Wind Tales

An amazing number of pilots got predictable results from attempted landings or departures in tailwinds. One South Carolina pilot, wanting to make our cut simulated a tailwind by departing uphill from a grass strip in poor visibility. The NTSB tells it best: “Upon reaching the crest of the hill, the pilot realized that the runway doglegged about 40 degrees to the left, but the airplane was traveling too fast at that point to be able to make the turn. The airplane left the runway and continued down an adjacent road before veering into [Yup!] a ditch.”

Then there’s the Wyoming wannabe ‘copter pilot, who “neither held a pilot certificate nor had any documented experience flying helicopters,” yet borrowed his employer’s Bell 407 to give friends a low-level “joy ride.” Unbound joy included buzzing one of the passengers’ homes, when they entered “an uncontrolled descent and collided with the ground.” Injuries were minor, so the non-certificated pilot “departed the scene,” only to be apprehended later in another state. The post-stupid investigation revealed that the non-pilot had given “joy rides” on several other occasions.

Don’t Need No Certificate

A plastic pilot certificate in the wallet does not a pilot make. But, just maybe, the dozens of training hours to earn that ticket do. Consider the “non-certificated pilot” in West Virginia who purchased a Cessna 172 and after a week of proud ownership—but no verifiable training—took a passenger aloft for a sunset flight. While attempting to land, the pilot had trouble figuring out how to actually do that, so he exhibited sound aeronautical decision-making and aborted the landing. Only, he didn’t demonstrate go-around mastery and plowed into those dang trees always lurking near runways…probably near a drainage ditch, too.

While a certificate does not make the pilot some training might have showed another pilot how to find the NOTAM stating that the airport had been closed for the past four years and that big X on the pavement didn’t mean Roman Numeral Runway 10. Here’s my favorite part of this Hooterville aero-disaster report: “City officials reported the pilot has operated aircraft from the airport since its closure and has continued to do so since the accident.”

Get Some Dual

As an instructor I’d like to report that the presence of a CFI is safer. Yes, indeed, that’s what I’d like to report. But sadly, CFIs were aboard for many mishaps. Most CFI-assisted accidents were of the “loss of directional control” variety, easily understood when considering how quickly and creatively a student can get a flying machine into the nether regions of the operating envelope. Screaming, “I got it!” to a terrified student death-gripping the yoke often comes too late. Been there, screamed that.

But let’s give a tip of the Foggles to a Nevada CFI in a Zenith CH750. According to the NTSB: “The pilot under instruction (PUI) and certified flight instructor (CFI) were practicing slow flight at approximately 200 feet above ground level.” No typo, that. Yes, slow flight. At 200 feet. Not too surprisingly, the airspeed deteriorated and the aircraft sank, eating up that precious 200 feet as the CFI called for more power and then even more power. (“Emergency power, Scottie!”) But still the aircraft sank.

Finally, the CFI—no doubt tired of feeling powerless in this relationship—took the bull by the tail, added power and pitched the nose up. Working hand-in-sock with the instructor, the PUI “pushed the nose down, and the airplane made an inadvertent landing, bouncing twice and coming to rest inverted.” An inverted landing after bouncing twice! Yet, miraculously, Laurel & Hardy crawled out uninjured from the impressive testimonial to the Zenith’s crash survivability.

CFI follies refocused our gaze on West Virginia where a student, a CFI and a passenger were flying a Cessna 172. The CFI “informed the student they would be conducting some mountain flying.” The instructor told the student to fly over a ridgeline and turn right at the first canyon. Don’t do it! It’s a trap!

But students trust their instructors, even this time, as it became clear it was the wrong canyon (Organ music up!), and they might not clear the approaching ridge line—dead ahead! (More organ music…) The square-jawed, geographically-challenged CFI took action and banked left to escape the canyon, followed by a “hard right turn” before coming to the realization that once boxed into a canyon in a Cessna 172 there’s not much you can do but level the wings and plow into the trees. They did. Although the 172 was mangled, a happy ending ensued as the three aeronauts walked away uninjured, while a doe shook her head in disbelief.

Fuelish News

Consider a possible dictionary entry for fuel mismanagement: Pilot managed to miss fuel in the aircraft. The upside of missing fuel is the diminished chance of fire following “Uh-oh.”

A Utah pilot flying skydivers reported, “that he expected the borrowed airplane’s fuel tanks to be full.” Unable to find a ladder, he relied upon the Cessna 172’s ever-so-reliable fuel gauges. “Throughout the day,” according to the NTSB report, “the airplane’s fuel quantity gauges gave indications that suggested the tanks contained fuel, and the pilot, therefore, continued to fly the airplane without visually inspecting the quantity of fuel in the tanks.”

This blissful flying-without-burning-fuel day concluded with a local sightseeing trip for three passengers, including the sight of the prop stopping mid-flight. Safety tip: If the fuel gauges don’t move in flight, they might be defective.

And then, there’s the ATP helicopter pilot in Florida who departed in a Robinson R22 with plenty of fuel on board. A certificated rotorcraft private pilot accompanied him on this ferry flight. Good flight planning called for a scheduled fuel stop, but on approach the ATP/PIC asked the private pilot to apply carburetor heat, which he did—almost. Instead, he “inadvertently pulled-out the engine mixture control with the mixture control guard, which resulted in an immediate total loss of engine power.” The ATP/PIC entered autorotation while the private pilot unsuccessfully attempted to restart the engine before the Robie struck trees, a fence and nosed over (into a ditch?). No injuries but ya gotta wonder if the ATP/PIC still relies on passengers to manage engine controls.

Art by Ben Bishop

And The Winners Are….

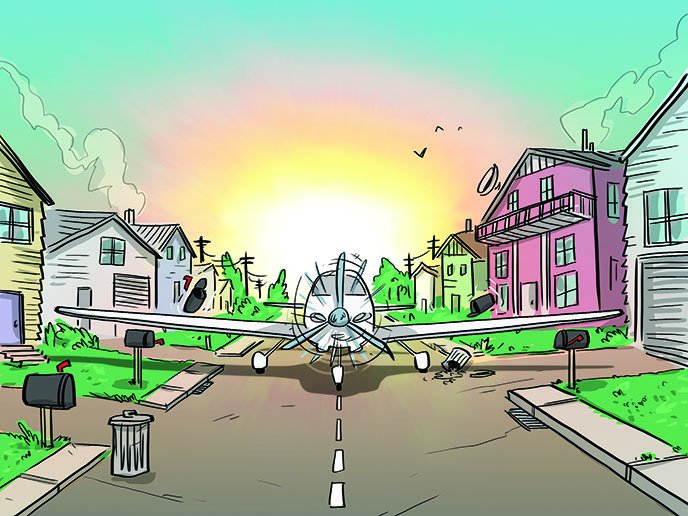

The competition came down to three finalists for Stupidest Pilot Trick of 2011. In third place was the Kentucky pilot who melded 1946 Taylorcraft technology with satnav as he approached his destination’s 5721-foot-long runway. Unfortunately, he landed at the wrong airport and too far down its 2400-foot runway for, as he reported, a safe go-around. The T-craft exited the runway and rolled into…yes, a ditch. It’s not reported if he ever looked up from the GPS screen.

Runner-up is a Cirrus pilot in Florida who also became overwhelmed by his high-tech panel. He was using GPS to align himself with the intended landing runway at an unfamiliar airport. Everything was fine until touchdown when the Cirrus wingtips began taking out mailboxes. The pilot must’ve been using the GPS’s street map page, because he landed in a residential neighborhood 1.5 miles from the runway. Cirrus might consider putting windows in their airplanes—Plexiglas, not Microsoft.

The winner of the 2011 coveted Clueless-In-Command (CIC) award goes to a Piper Colt owner in Maine whose story is best narrated by a witness who reported that “he was mowing his grass when an airplane crashed in his front yard.” The witness added, “The pilot exited the airplane and instructed him not to notify the police. The pilot left the scene and returned a short time later with another individual and a forklift.” After making their slow-speed getaway with the crumpled two-seater atop the forklift, the pilot and accomplice hid the wreckage in a storage facility without notifying authorities.

This almost flawless caper was finally unmasked by dogged FAA sleuthing and numerous witnesses who said, “Yeah, I seen it.” And, while it’s not illegal, per se, in Maine to interrupt someone’s mowing, it is against FARs to do so in an airplane without a proper pilot certificate. No mention was made if the non-certificated Colt pilot was sentenced to community service mowing the witness’s lawn.

Paul Berge, former editor of IFR, is a free-lance author and independent film maker. He flies his Aeronca around Indianola, Iowa.