Every year we worry that the NTSB accident reports won’t provide us with tales of pilots unencumbered by forethought. Every year, our fears are allayed.

As the holiday season gives way to the interminable darkness of winter, we pause in our discontent to honor, ridicule and learn from those pilots who’ve slipped the surly bonds of reason and, once again, slapped the face of God-knows-what foolishness.

Each year we review non-fatal accident reports for which the NTSB has assigned “probable cause.” Today we spotlight the unflyable antics of 2008, an election year during which, among other non-aviation silliness, the Dow dropped over 400 points in one day. Given 2008’s general insanity, perhaps we should cut the pilots who erred a little slack … nah.

Fuel’s Fools

Not all mismanagement of liquid funds was in the fiscal/political realm. Way too many pilots mismanaged fuel in the tanks, mostly by just not putting in enough and trusting that any deficit would magically cure itself. Witness the Cessna 177RG pilot who departed Frederick, Md., and, while on approach to Tallahassee, Fla., experienced an unexpected engine failure followed by the Cessna crashing through power lines before stopping on a road.

There was no post-crash fire, because (any guesses? anyone?), yes, the airplane had run out of gas. The chagrined pilot claimed he’d done everything humanly possible to stretch the fuel-starved Cardinal’s cross-country endurance: “I even rocked the wings to use every drop of fuel.” Like politicians, pilots say the cutest things.

Several pilots failed to notice water and other contaminants inside aircraft fuel tanks during preflight and quickly learned that engines don’t run so well on water and dirt. You do sump your tanks during preflight, right?

A Flite Bike powered-parachute misadventure in Kansas injured one of the two people on board when the PIC departed with the fuel valve in the “off” mode. This led to a stall/mush crash less than seven minutes after lift-off. Seven being the pilot-verified number of minutes the Flite Bike will run on the header tank alone. Which begs the question to any passenger: Do you really want to fly in something called a Flite Bike?

Honorable mention for fuel folly goes to the California pilot who swears he didn’t know that the Cessna 150 he was flying had been modified from its stone-simple, factory-installed, On/Off valve to a more brain-teasing four-way valve to accommodate the extra fuel tanks that must have been installed—we can only presume—by impish fairies without that pilot’s knowledge.

Wild Rides

Fuel-thieving gremlins weren’t the only evil sprites bringing down aircraft in 2008. Several pilots dinged their machines after close encounters with “dust devils.” There was no record of similar hijinx from ghost riders in the sky.

Still, one Bonanza pilot in Georgia crashed into a fourth dimension when, as he told accident investigators, he’d encountered an “air pocket,” which, as we all know, adversely affects one’s seat-of-the pants flying skills.

Alaska pilots continue to bust airplanes with great lan by landing on boulders that are too large, sandbars that are too short or plowing into hills that are just a little too tall. Not sure how these backcountry Goldilocks get hull insurance that’s just right.

Far too many pilots in the lower 48, who are rarely tasked with dodging grizzlies on the tundra, continue to send airplanes to the shop after hard landings, bounced landings and what’s lumped into the this-guy-can’t-fly category: “runway loss of control” (RLOC). Usually that means they can’t handle any crosswind. Not surprisingly, many of the RLOCs came at the feet of tailwheel pilots, and most disconcerting were the ones that occurred with a CFI onboard.

A little advice from one instructor to another: I know it’s tough making that split-second decision in the flare whether to let the student continue a sloppy approach or snatch back the controls to save the day. But when the student is yelling “Yeeeehaw!” without inputting any aileron into the crosswind plus opposite rudder to keep the nose straight, it’s time to earn your $20 and retake command.

Gimme a Brake

Several tailwheel pilots tipped their machines onto the spinners after landing, because they made the mistake of using brakes. Most older taildraggers—Luscombes, Champs, Taylorcrafts—have awful brakes with awkward heel pedals. When stepping up to a Husky or Scout, go easy on the toe brakes.

But brakes were just a part of a Georgia instructor’s misfortune in a Piper Cherokee 140, which, like many older Pipers, only had toe brakes on the student’s side with a hand brake available for the instructor. While taxiing out the student told the CFI that the brakes seemed “weak,” but the instructor was a bit preoccupied with an uncooperative door latch. Most CFIs teaching in worn-out old Cherokees know that the brakes stink, and the doors are tough to close, but, hey, you don’t make money canceling for non-essential items. They took off. After all, once you’re in the air, who needs brakes?

During the fourth touch-and-go, the Cherokee’s door popped open on takeoff roll. Despite the fact that a Cherokee—and most other airplanes—will fly just fine with a loose door, the CFI chopped the power and told the student to apply the brakes. You know, those brakes that the student had earlier reported as “weak.”

Surprisingly, the brakes had not mended themselves, and the wayward Cherokee ran off the runway, down an embankment and came to rest with diminished resale value. NTSB notes that the Cherokee POH includes this salt-in-the-wound statement: “An open door will not affect normal flight characteristics, and a normal landing can be made with the door open.”

Meaning, fly the airplane, land and then close the door. The same POH does not mention that the Cherokee will stop properly without brakes, an editorial omission, no doubt.

Working Craft

Helicopter and balloon pilots still insist upon wrapping themselves into power lines, windmills and cell-phone towers. Granted, many helicopter accidents involve ag or other commercial operations in fairly stressful situations and often in confined areas. But the California accident report that begins, “The pilot was spraying fields at night,” almost writes itself. The spray pilot said he “was aware of the general location of the power lines in the area.”

Unfortunately, it was the specific location that caught him by surprise when he felt a sudden bump accompanied by a blinding flash resulting from the shower of sparks emitted by the arcing high-tension lines. Calamity turned to hairy-chested heroics when, post crash, the chopper pilot managed to escape and, overcoming temporary blindness, fought his way back through the tangle of live wires to shut down the helicopter’s engine, thus saving untold meaningless billable tenths on the Hobbs.

A Texas Super Cub ag-flying accident needs little more than the NTSB’s introduction: “The non-certificated pilot …” We could stop there and agree it’s stupid enough, but there’s more: “… said he was herding cattle at a low altitude when he entered a steep bank, stalled and crashed.” Damn cows should be outlawed.

Count Fingers, Not Blessings

Since the December 1903 day when Wilbur called to Orville, “Hey, Bro, gimme a twist,” pilots have been hand-propping piston engines. It’s a reasonably safe operation with competent, five-fingered hands at the prop and a qualified pilot at the controls.

This wasn’t the scenario one December morning in Texas when the Cessna 150 pilot (yes, 150s have electric starters) attempted to turn the propeller by hand in order to “limber” the oil. Needless to say—but we’ll say, anyhow—the mag switch was hot and the engine started. The non-pilot left at the controls for this operation might have been able to stop the Cessna, had he not been six years old. Luckily, the child was unharmed by the subsequent encounter with the trees. We can’t say the same for the Cessna.

Hand propping a Cessna 150 might seem like child’s play, so why not upgrade to, say, hand starting a Cessna 210? An Alabama pilot must’ve thought it was a good idea (as so many bad ideas seem at the time) to start the Cessna 210G by hand with—you guessed it—a passenger strapped sacrificially in the right seat. The NTSB report tells it best: “During the first attempt …”—the first attempt!—”… the engine cranked but stopped. Subsequently, when the engine caught, it overpowered the parking brakes.” Author’s note: 285-hp is likely to do that. The 210 taxied into its hangar and chewed up another airplane, no doubt impressing both passenger and FBO. At least they didn’t have to move the airplane back into the hangar by hand, because 210s are quite heavy.

Even without hand propping and with a qualified PIC on board, a Texas Cessna 172 commercial pilot managed to taxi into trouble when he “dropped something on the floor.” Don’t know what that something was, but it must’ve been vital to the safety of flight, because, with the engine running, the pilot “moved his seat back so he could reach down.” While the pilot searched the floorboards, the airplane taxied unassisted into an expensive insurance claim. Add this to your pre-taxi checklist: “Please remain seated, captain, until you’ve turned off the engine.”

A Time To Panic

Nerves of steel weren’t in a Piper Saratoga pilot’s kit when approaching an Alabama airport, where “he noticed some trees about 800 feet from the approach end of Runway 4.” The report says, “The trees scared him, (so) he purposely came in higher.” When that resulted in touchdown with only 800 feet of runway remaining, he discovered two things: No amount of braking was going to salvage this, and it was too late for the go-around he should’ve initiated when the trees first scared him. The airplane crashed into a thicket of even scarier trees at runway’s end.

A Piper Dakota pilot cruising at 5000 feet IFR felt the engine run rough and soon smelled fuel fumes. Wisely, he told ATC he’d make a forced landing and selected a 1065-foot emergency field. For a Dakota using full flaps and landing at the POH-recommended 65 knots, that should require a POH-optimistic 610 feet of ground roll. Sadly, the pilot—understandably stressed by the prop sitting still out there—selected only 10 degrees of flaps and touched halfway down the field at “about 90 knots.” Complex math reveals that 1065 feet divided in half leaves 532.5 feet available landing distance. An enterprising fence did its best to slow the Dakota down so it wouldn’t be so hard for the trees to stop it.

Better Lucky Than Stupid

If at first you don’t fail, try, try again. A Cessna 172RG pilot who took a hankerin’ to buzz an Illinois lake one winter day had no problem on the first 100-foot pass. But on that second low pass, the pilot detected a “thump noise,” and the engine quit. No definitive explanation was given for the “thump noise,” but it may have been related to the wire strung 40 feet above the lake, there for the sole purpose of snagging passing Cessnas. It worked, and the disabled airplane nosed over after landing in a muddy field.

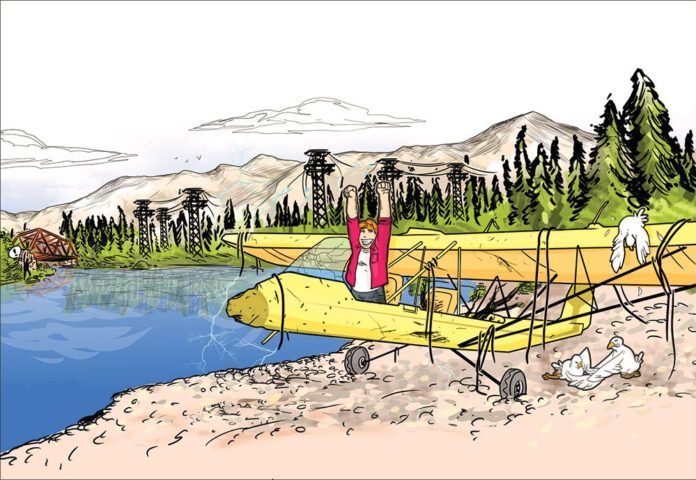

Maybe not a buzz job per se, but this California pilot of an open-cockpit experimental earns IFR’s Abbott and Costello stupid-flying award by “flying at a low altitude over a river into hazy conditions and looking directly into the setting sun.” That alone wasn’t awkward enough to qualify for the award, until the pilot turned to miss a flock of birds (insert chicken squawks here), hit transmission wires (boing-ploing!) and “severed the airplane’s wing support structures.” It gets real slap-stick as the “impact with the wires forced the airplane to a lower altitude and under a bridge in the airplane’s flight path.”

Are we down yet? Nope. “After flying under the bridge and exiting on the opposite side (a la Paul Mantz in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World), the airplane impacted a second set of transmission wires with its landing gear legs (bling-ploing!). “The pilot,” the NTSB report continues, “then made a successful forced landing on a river gravel bar and came to rest upright” to audience cheers as the music rises, and we roll the closing credits on another happy ending to the stupidest/luckiest pilot trick for 2008.

Kids, don’t try any of these stunts in your home airspace, because, while some of these errant pilots were trained professionals, all the stunts were really, really stupid. And be extra vigilant up there, because 2012 is an election year shaping up to be even dumber than 2008.

Paul Berge ensures our yearly Stupids contain no references to Champs owned by someone with the initials P.B. His website is www.ailerona.com.