This maze of hallways is the archives of aviation’s greats—not the Stupid Pilot Tricks Repository. We’re awed by images of the Montgolfier brothers and their good sense to launch the world’s first flyable aircraft with a sheep, rooster and duck before stocking its basket with humans (who weren’t themselves). While they were brilliant, Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier is wrongly credited with the ultimate flight safety decision-making phrase, “Will doing this make me look stupid in the NTSB report?”

We read of astounding accomplishments, including the first outside loop, and the genius of Jimmy Doolittle with his doctorate in aeronautical engineering from MIT. After setting numerous records while surviving the slaughterhouse of air racing in the 1902s and ’30s, he retired, saying, “I have yet to hear anyone engaged in this work dying of old age.” He died quietly at age 96.

On a nearby wall we see Louise Thaden’s portrait and the list of records she set while fighting those who claimed that women didn’t have the right stuff to be pilots. After smoking a field of men and one other woman by 45 minutes in the 1936 transcontinental Bendix Trophy in a Beech Staggerwing, she moved to more mundane endeavors including a 196-hour endurance flight involving aerial refueling and then working as a demonstration pilot for Beech Aircraft—trying to remain calm while showing new airplanes to pilots with more money than skill.

Lost in contemplation of aeronautical genius, we wander past numerous signs proclaiming “No Admittance,” “Do Not Enter,” and “Stay Out,” only returning to situational awareness facing a worn and cracked wooden door covered with peeling paint and yellow “Caution, Pilots Cooking” accidentscene tape. Above the door a fading sign proclaims, “Abandon Hope, All Ye Who Enter Here.”

Of course, we try the doorknob.

It screeches. But we’re in the bowels of the archives and nobody hears it. A gentle push opens the door into a narrow, dingy, cobwebbed hall lined with ancient filing cabinets. Could this possibly be what we seek? We boldly enter, inadvertently stepping on what looks to be a small bladder-like device. The whoopee cushion may be old, but it still works. Loudly. For several seconds.

Frozen, we fully survey our surroundings. On a nearby desk is a dustcovered invitation to an annual Stupid Pilot Tricks reveal party. A look at the filing cabinets reveals that each drawer is labeled “SPT” with a year. We’re here.

We’ve found the mother lode. We open the file for the year 2017 and soon confirm that for every Neil Armstrong acing a moon landing, there are others saying, “No problem, there’s plenty of runway.” For every pilot calculating takeoff weight, temperature, and wind before selecting the departure runway there are aviators confident that they won’t have any trouble taking off uphill … downwind … from an intersection … at 90 degrees … in the mountains.

Opening the 2017 drawer, no NTSB investigators were harmed when the drawer fell out of the cabinet and all of the fatal accident reports blew out of our reach.

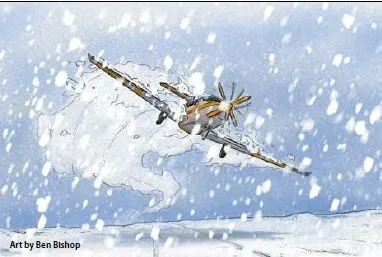

What’s a Little Snow?

Our first paragon of judgment was departing from a high-altitude airport in his single-engine turboprop. The weather stank—freezing fog and a 500- foot ceiling. Oh, and it was snowing. Hard. Economically, the airplane was parked outside. Determined to depart and apparently not impressed with all the guidance that lift-generating surfaces be completely free of contamination before takeoff, the pilot wiped snow off of the wings “as best [h]e could.”

Heavy snow continued as he taxied for takeoff, resulting in an additional “light accumulation of wet snow” on the wings. The pilot later reported that after pointing the airplane down the runway and moving the power lever from quiet to noisy, snow “sloughed off” the wings under acceleration. Sure, that’s a clean wing.

With help from ground effect, the airplane lifted off and climbed. To 150 feet. At that point the pilot said that it yawed left, so he applied right aileron (??). Having superb vision, he “could see a stall forming,” so he shoved the nose down and pulled the power to idle. Moments later he and the airplane arrived, left wingtip first, back on the ramp, using 600 feet of it to slide to a stop.

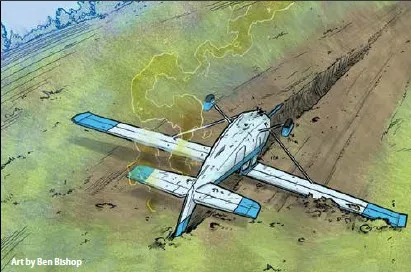

Opening the “It’s not quite right but it’ll be okay” file tab, we were impressed by the owner of the Piper Seneca with a “significant” oil leak in the left engine. He had not one, but two A&Ps look at the engine. Neither could find the source of the leak. After topping off the oil and adding some fuel, the owner apparently decided that if two technicians couldn’t find the leak, it must not exist, so he continued his “long” flight with three passengers. Some 15 miles short of the destination the low-oil-pressure light for the left engine illuminated. He pressed on. Five miles out the engine lost all oil pressure and power and “the prop feathered.” He pressed on.

Having only one working engine, the pilot elected to land downwind. You guessed it—high and fast. Cue single engine go-around noises. The aviator quickly discovered that the rate of climb was abysmal. Hoping to improve matters, he shoved the throttle on the remaining engine all the way forward, ignoring that he had already brought power up to max manifold pressure.

Yes, overboosting a turbocharged engine is not a good thing. He of the sweaty palms quickly became one of the few twin pilots to experience a double engine failure with plenty of fuel. More expertise followed; rather than glide into the trees, level, under control, he stalled it, lost control and hit the trees in a steep nose-down bank.

But It’s Not Done

This paragon to patience was determined to fly his Cessna 210. He faced a trivial problem—it was in the shop for annual, on jacks awaiting parts for the landing gear. The mechanic left for lunch. The pilot let the airplane down off the jacks, replaced the airframe panels that had been removed, pulled the airplane out and tried to start it. About that time the mechanic returned, ran to the airplane and confronted the pilot, again saying the annual was not complete and it couldn’t be flown. The insistent pilot started the engine and left.

Selecting gear down at the destination, the left main gear would not extend. After the noisier (and shorter)- than-normal landing, inspectors found that a gear saddle had failed in fatigue, precluding the left main from extending. Weren’t they awaiting parts?

In the “I Was So Close,” folder we read of misplaced optimism about the degree of accuracy of portable GPS and a pilot’s exaggerated sense of his precision in following their guidance. Near his destination on a “marginal-VFR” night, the pilot clicked on the runway lights, saw the runway lights, and started down. But he ran into ground fog at 300 feet—no more lights.

Undeterred, and apparently not considering the subsequent NTSB report, he continued, using the moving map and GPS altitude. While in a left turn, he hit the ground—a mile short of the runway.

Closing out that folder, we looked at the one-two punch a pilot applied to his Cessna 182. Attempting to land on a paved runway, he touched down more or less level just before the pavement began. Sadly, the threshold included a lip several inches high. The raised pavement removed the 182’s nose gear.

It’s never too late to go around. Perhaps now leery of pavement in general and forgetting that if you’ve got a gear problem it’s wise to land on pavement because the airplane will slide, our elevated-pulse pilot chose grass for his next landing.

As you guessed, once the remaining nosegear leg touched down, it dug into the turf, flipping the airplane.

Swing That Prop

We thought we’d seen all the stupid pilot tricks prop-starting an airplane. However, the pilot of a Piper J-5 found a novel way of having a non-pilot help.

Swinging the prop with a “we don’t need no steenkin’ chocks” attitude, the pilot had positioned his passenger in front of the horizontal stabilizer to keep the airplane from moving. Let’s see: immovable human in front of aircraft structure. Yeah, that should work.

Leg up, down, swing the prop, engine starts. At high rpm. (Need more?)

Yes, the passenger proved movable. The pilot grabbed a strut but fell trying to get into the airplane. That got the airplane going in circles. In retaliation for being fired up by a stupid pilot, the airplane ran over the pilot before it threw up its metaphorical hands in despair and ran into maintenance equipment— which then needed maintenance.

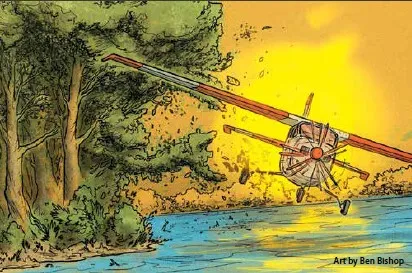

A Safe Landing, Now What?

We generally think a precautionary landing shows good judgment. It’s what the pilot does after that landing that shows whether they have the right stuff, or end up here. We noted with pride that a Stinson SR9 pilot responded to a rough-running engine by making a safe landing in a soybean field. The pilot doubled down on that good judgment because he then had an A&P examine the engine. After several run-ups, the technician opined that it was carb ice.

The next step was to fly the airplane out. The pilot decided to share that excitement with two passengers. The temperature, weight, wind, and runway/soybean-field condition meant that by the time the big Stinson lumbered a mere five feet into the air, it met the seven-foot stalks in the adjacent corn field. Not surprisingly, mature corn stalks are an effective speed brake. The Stinson stalled within seconds, flipping onto its back. One wonders about the subsequent conversation in the cabin.

Just a Little Below Minimums

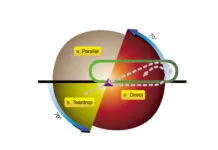

Going below minimums on an instrument approach is a common stupid pilot trick that many survive. We read the report of a pilot making a night GPS approach who claimed that he saw the approach lights but was “a little right of course” and “fixated” on the instruments while attempting to correct for being off course. He said that he hit the tops of some trees—substantially damaging the airplane—pulled up and landed. The weather was 200 overcast with ¾-mile visibility.

But, brushing the treetops and flying away is kind of a yawner in the big world of stupid pilot tricks.

Then the sun came up and turned this into a classic for the record books. The GPS approach is over a lake that’s below the runway elevation. Second, as the drawing shows, the pilot didn’t brush treetops on the lake shore, he strained the right wing and fuselage through a tree, carving out a “C” shape in it. He was at or slightly below the runway elevation, some 3000 feet short of the runway. Let’s see, we’ll go 200 feet below DA, with the glideslope needle pegged in the “uh-oh” position, knowing that this is our home airport and there are tall trees a half-mile short of the runway Yeah, that’ll work.

Under the “It Was an Honest Mistake” tab, we saw an ag pilot who claimed he was “testing the spray system at maximum pressure at a specified airspeed.” That sounds good—a test that can be conducted at a reasonable altitude (you’ve got to look inside the cockpit at dispersal system instrumentation) and away from people, vehicles and buildings.

While carrying on this task, our very professional agricultural aviator “lost focus outside of the airplane” and managed to hit the only tractor in a big field. But wait! There’s more. The tractor was in motion and the operator was injured when he was thrown from the tractor by the collision. But wait! There’s still more. Apparently this conscientious, cautious professional pilot had previously buzzed this tractor operator and his supervisor a number of times before. He had to be good; he could hit a moving target while losing focus outside of the airplane.

Oh, Give Me a Home

Having a home on an airstrip is the dream of countless pilots. If that airstrip is long enough for the family airplane it’s even better. One pilot sought to launch into the delirious burning blue from his home grass strip in the family Cherokee. He rose into the air briefly, then descended and “touched down hard.” Wash, rinse, repeat—he continued to lift off, only to subsequently touch down a number of times until he determined that he would not make it over the trees at the end of the runway. Apparently, the pilot’s takeoff Plan C was to abort the takeoff and stop before running off the end of the airstrip, because he implemented his Plan B. That involved making a left turn and motoring across two adjacent fields,

through a ditch and using a barn as tackling dummy. It worked—the barn successfully stopped the airplane. The pilot was unhurt. No information was provided about the long-term viability of barns as EMAS.

We’ll close with an accident report that gave us faith that stupid tricks around airplanes are not all performed by pilots—and that even though a pilot

does everything right, there’s a chance that some idiot will mess things up. The pilot of a Beech twin made all of the appropriate radio calls as he approached and landed at a nontowered airport. Shortly after touchdown, with braking underway, the pilot saw a truck—pulling a loaded flatbed trailer—approaching the runway. The truck slowed briefly, but then accelerated onto the runway, crossing it.

The pilot swerved hard and almost made it, unfortunately, the aircraft’s wing and the trailer tried to simultaneously occupy the same space. After everything was brought to a stop, the truck driver apologized to the pilot saying, “I thought I could beat you across the runway.” The report does not indicate whether a dope slap was administered. Because the accident occurred in Texas, rumor has it that it is possible the pilot could have carried out such an admonition under the State’s “He had it comin’” common law “reaction to stupid” doctrine.