How does your GPS navigator handle a leg to a specific heading or to a specific altitude? Do you fly these with the confidence of Captain Picard of the Enterprise, or of Doctor Who pushing a button to see what happens?

These legs are common, particularly as the first step on a missed approach: “Climb runway heading to 1300, then …”

Before you scoff because you handle those all the time, note that pilots are botching these procedures enough that Garmin recently issued Service Advisory 1558/A. In a nutshell it says: Know what the navigator installed in your aircraft will do when the instrument procedure says to fly on a specific heading or to a specific altitude.

I might scoff, too, if I wasn’t caught off guard on a missed approach by an unexpected button push due to this exact issue. I expected the avionics setup to have an ability it didn’t.

An Old Issue

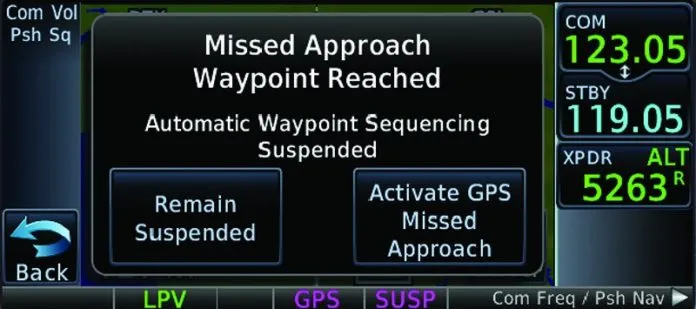

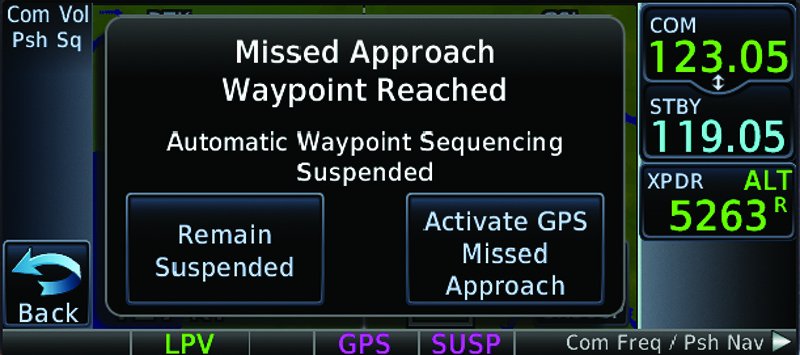

When IFR by GPS was young, long before WAAS, we quickly discovered a hole in the guidance offered by the pink line. (OK, the magenta line. But it sure looks pink to me.) The GPS suspended waypoint sequencing as soon as you crossed the missed approach point (MAP). If you had to execute a missed approach, you would restart waypoint sequencing and the GPS would give guidance from the current position to the first fix on the missed approach, usually the missed approach holding point (MAHP).

The catch was on procedures calling for a climb on runway heading to a specific altitude before turning to the MAHP. The GPS knew track, but not heading. It knew GPS altitude, but not corrected barometric altitude. So that initial climb was simply omitted from the GPS flight plan.

If you unsuspended the GPS before climbing to the required altitude, it gave guidance for the turn—even if the airplane was too low and on the wrong heading. The pretty pink line could blithely guide you right through a mountain.

The fix was simple: Don’t unsuspend sequencing until you manually fly the heading up to the required altitude.

It’s not always as simple today.

A New Twist

If your GPS does know your heading and/or altitude, it can offer more assistance. That’s what I thought would happen on the RNAV (GPS) Runway 25 approach at Sanford, Maine (KSFM). I was flying an older Cirrus SR22 equipped with the original Avidyne PFD but two new Garmin GTN 650s.

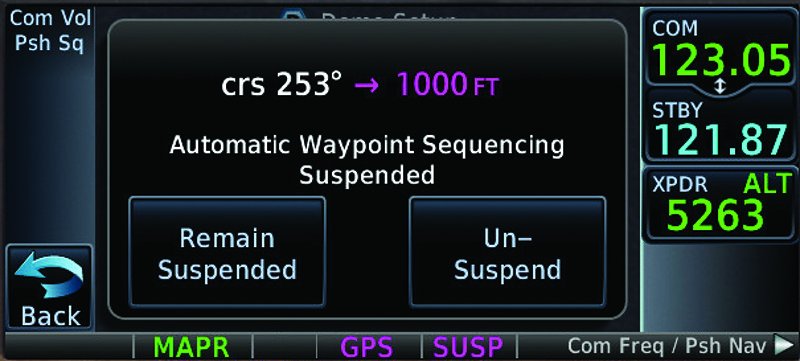

At the LPV DA of 496, I reconfigured for a missed approach climb and tapped the “Activate Missed Approach” button on the 650 as my hand was on its way up from the flaps. The 650’s flight plan showed it knew about the climb to 1000 feet before turning left to GUNTY, and I expected the Avidyne PFD’s altitude output to tell the 650 when we reached 1000 feet. This way I’d get a reminder right on the PFD to change course passing 1000, but not before.

Except it didn’t do that. Instead, a second pop-up appeared on the 650 asking me to confirm I was above 1000 feet. I wasn’t. Since this was VFR practice, I acknowledged it anyway just to see what would happen, and got immediate guidance for the turn. I climbed the remaining 200 feet before chasing the pink line.

The 650 didn’t have an altitude source the way a Cirrus with dual GNS 430Ws I used to fly did, and that changed their behavior. What was a fine habit had become a bad one, even though the avionics were more advanced. At least there was a warning screen.

Approaches, By George

Autopilots offer more traps for the unwary. Start with a Cirrus with no altitude input, like the one I flew, and suppose I flew the approach coupled to DA.

At DA, I could manually pitch for a climb, add power and raise flaps, and then reengage the autopilot. Because the GPS can provide guidance on the missed approach, it’s common to engage the autopilot in nav mode to follow the final approach course until you resume sequencing. However, that only works if the initial climb on the missed is the same heading as the final approach course. That’s not always the case, so you might need heading mode.

Add an altitude input, and I could unsuspend sequencing early and engage nav mode, knowing the GPS won’t advance to the next step in the procedure until I climbed high enough. In fact, the 650 wouldn’t even pop-up that second screen. It knows so it won’t ask me. When the aircraft reached 1000 feet, it would automatically turn left for GUNTY.

Now get this: If the GTN had heading information from the PFD, I could engage the nav mode and have it fly a heading—yeah, actually turn to a specific heading, not course—and fly to an altitude, and then turn on course to the next waypoint. GNS 400/500s don’t have that option.

All of this assumes you have roll inputs to your autopilot, a.k.a. GPSS. Without GPSS, your autopilot could hold any of the straight legs, but you’d have to do the turns.

Just for fun, let’s make this a G1000/Perspective aircraft with a Take Off and Go Around (TOGA) button. At DA I press TOGA, advance the throttle and raise flaps. The autopilot remains engaged and flies wings level with a climb pitch. I re-engage nav immediately and the avionics do the rest: climb to 1000, turn left and climb to 2400 at GUNTY, and hold. The system can do this because it knows altitude, heading and even pitch attitude. That’s all the information it needs.

Got all that? Actually, it’s gets worse. For example, some G1000 installations allow the autopilot to stay coupled and others won’t. Some systems are smart about whether they turn right or left per the procedure. Others just look at which ways is shorter around the compass rose, and there are procedures that require turns from runway heading to the next course in the “wrong” direction of more than 180 degrees due to obstacles.

The takeaway is to know what your system can and can’t do. Know what information it has and what it assumes when you let the computers fly.

Speaking of Gaps

Some procedures are real head-scratchers until you think them through. Look at the missed for the ILS or LOC/DME Y Runway 19 at Rutland, Vermont (KRUT). It’s a complicated missed with a climb on runway heading to an altitude, then climbing inbound on a radial to a DME, followed by a turn outbound to intercept a different radial, probably while you’re still climbing. Glancing at the flight plan and the moving map shows two gaps, one off the runway and one when turning to the outbound radial.

How much can your GPS navigate? Most WAAS setups need you to manually handle the climb and tell them when you’re high enough to skip the first gap, but have no problem with the second gap and the outbound turn. The turn isn’t depicted because the actual intercept is dependent on groundspeed throughout, so there’s no way to know where the course lies until it’s flown.

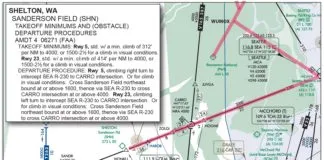

My suspicion is heading and altitude legs more often cause surprises for folks on departures. Look at the COASTAL SIX departure, which covers many airports around Hartford, Connecticut. If you depart Runway 20 from Hartford-Brainard (KHFD), you’ll start by climbing on a 175-degree heading. Somewhere above 1300 feet, you should expect radar vectors. So you’re on that heading until ATC speaks up. At some point you’ll either get direct to a fix on the rest of the published departure, or you’ll join a leg of the departure.

How will your GPS handle that?

Loading the departure with a GNS 400/500W shows the departure airport and then the next GPS-navigable leg: HFD to THUMB. The climb and vectors are completely up to you.

Load the same departure into a GTN 650/750 and you’ll see three legs between the pavement and HFD: a course to 420 feet, a heading of 175 to 1300 feet, and a heading 175 to a vector. If the GTN has neither heading nor altitude input, each sequence on this flight plan is up to you until you intercept a leg past HFD. If it has altitude input, it can sequence to the second leg, but can’t provide guidance because it doesn’t know your heading. If it has altitude and heading, it can guide you all the way to leg three, but lacking the ATC clairvoyance module, it needs you to sequence it once vectors are complete and you resume own navigation. (“Own” = On-board WAAS Navigator. Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Danger Will Robinson: If the GPS suspends while you’re on a vector and then you simply restart waypoint sequencing, it assumes you want the leg from HFD to THUMB. If ATC vectored you to intercept YODER to CCC instead—quite likely—the GPS will turn you around and right into trouble. Correct procedure is to activate the leg you need to intercept and use the right combination of heading and nav modes if your autopilot will do the turn on course.

G1000s have their own, different, way of handling this. They insert a leg called Manual Sequence, which is your cue to fly as you’re told until it’s time to engage computer navigation again. The same situation applies about ensuring you sequence to the correct leg however.

In case you’re wondering what the course to 420 feet is at the beginning of the procedure, that’s the Stupid Pilot Safety leg. Remember that all departure procedures assume a climb on runway heading to 400 AGL. Hartford’s airport elevation is 18 MSL.

Remaining Computer Current

There are really three kinds of instrument currency. Two of them, basic attitude instrument flying and instrument procedures (“keeping the greasy side down” and “flying the black line”), have been with us since Jimmy Doolittle made a blind takeoff.

The third is avionics proficiency, and it became critical with the moving-map IFR GPS. In fact, I think you could say it happened big time when Garmin introduced the first GNS 430. Buttonology is now an inexorable part of instrument flying. Call it “flying the pink line” if you want, but a better way to think about it is “commanding the automation.”

Your goal is to feel like the captain of the Starship Enterprise, calling out orders from your chair, knowing exactly what each officer under your command can and can’t do in a given situation. Of course, you’re ready to step in and take over when an ensign shouts, “Captain! Navigation isn’t responding!”

Jeff Van West loves avionics, but still wants a system that prompts for a missed approach by chanting, “To-GA, To-GA, To-GA.” Preferably with a photo of John Belushi on the MFD.