The optimistic among us, besides having sunnier dispositions when asked to copy a reroute or enter a hold, like to assume positive outcomes during flight planning. This means looking for bright spots (literally) in weather forecasts and finding the upsides to adjusting departure times. While it’s nice to have a good attitude in flight, completely ignoring the pessimist in you can result in not-so-positive results.

If you’re one of those types, you might gloss over items like en-route charts. Scrutinizing these hasn’t been your forte, mainly because you like to fly your speedy, GPS-equipped bird direct to your destinations. You’re now so accustomed to hearing “cleared as filed” from your home base in up-state New York that you’ve gotten out of the habit of poring over airways and en-route fixes. Now, with a longer trip taking you out of familiar airspace, you’re about to get disappointed—more than once.

Why the Reroute?

Your springtime cross-country flight will take you from up-state New York to Independence, Kansas, with a fuel stop halfway at Columbus, Indiana. It’s 966 NM in total for the two legs, and with winds aloft holding below 20 knots until entering Kansas, you can expect to make just one stop at the halfway point. However, it’ll be a long day with about six and a half hours of flying.

You file for 12,000 feet and 200 knots from Binghamton, New York to Columbus. Always the optimist, you assume a clearance direct. Now, your more pessimistic peers would think it sounds too good to be true, so they’d want to pull up the chart to check for anything that could get in the way. Sure enough, there’s more than something.

Unbeknownst to you, the direct route slices through the middle of the Duke Military Operations Area, and it’d take about 52 NM to traverse it. You remain blissfully unaware while getting “cleared as filed” and launching right on time. You’re hardly an hour down the road when you hear from local approach control: “Amendment to your route; advise ready to copy.”

It takes a minute on your part to advise, having to flip your way around the tablet for a scratchpad. You get direct to XPLOR (to the southwest of your route) then direct destination; you copy this and adjust accordingly. That wasn’t so bad; just one fix hardly makes a difference. Curious, you query ATC, and are told the change is “due to military airspace becoming active.” That’s when you look for the MOA.

More MOAs, and RAs

Recall that MOAs separate IFR traffic from military traffic, which could be doing any number of things like “air combat tactics, air intercepts, aerobatics, formation training, and low-altitude tactics” (see Chapter 3, Section 4 of the Aeronautical Information Manual). Can you, the IFR traffic, request a route through active airspace? Sure, according to the AIM, but with all the potential conflicts, it’s unlikely to be approved.

You tap the airspace in question on your EFB; the Duke MOA is hot from 10 until 3 p.m. local, 8000 to 17,999 feet. You’d like to pick ATC’s brain on it, but don’t. On the plus side, you’re not in a big hurry to get to Columbus. Besides, it’s certainly safer to avoid stuff like air combat tactics.

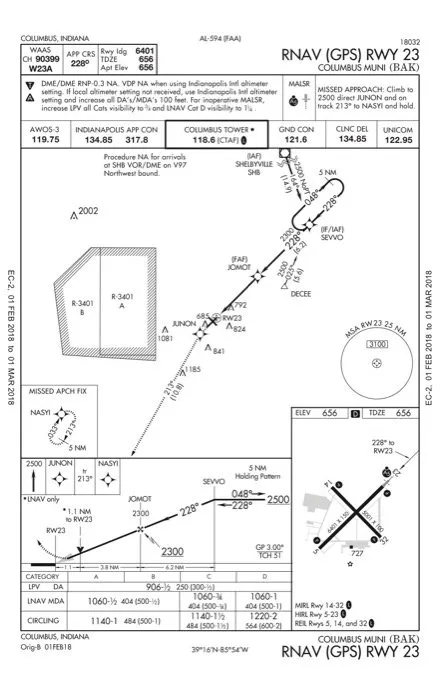

The rest of the leg is uneventful and after a leisurely break at Columbus, you call the tower for a clearance to Independence. It happens again. Your route is no longer direct; you’re to depart Runway 23 and fly heading 180, climb and maintain 3000 feet. Now you wish you had looked into that hashed line on the GPS, so you inquire. Turns out that the cluster of four MOAs (Racer A, B, C and D) is active just west of KBAK. What’s more, embedded within the northern half of the MOAs are R-3401A and R-3401 B.

Again, if you had bothered to check, you would’ve known that the Restricted Areas are active most days and run up to FL 400, with some of the MOAs going to 17,999. You’ve nowhere to go but around. Those of you who did the homework know that AIM 3-4-3 says, in part, that RAs “denote the existence of unusual, often invisible, hazards to aircraft such as artillery firing, aerial gunnery, or guided missiles.” Sure, you can ask to go in, but that would only work if it’s cold. (For you airspace geeks, 14 CFR Part 73, Subpart B has guidance for restricted area clearances).

Not Through Yet

In hindsight, you realize you could’ve filed a different route to avoid the airspace or, better yet, stopped prior to Columbus and filed for something that would allow you to overfly Racer A, which only goes to 3999 feet. You tap this into your route and see that it just avoids the corner of R-3401A. Optimist that you are, you note that this helps lighten the workload before takeoff.

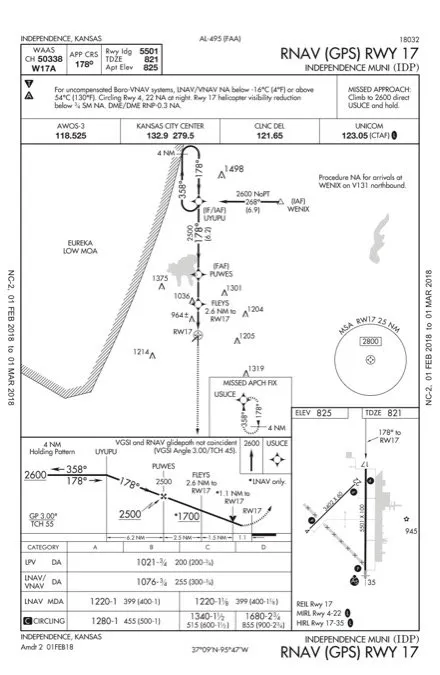

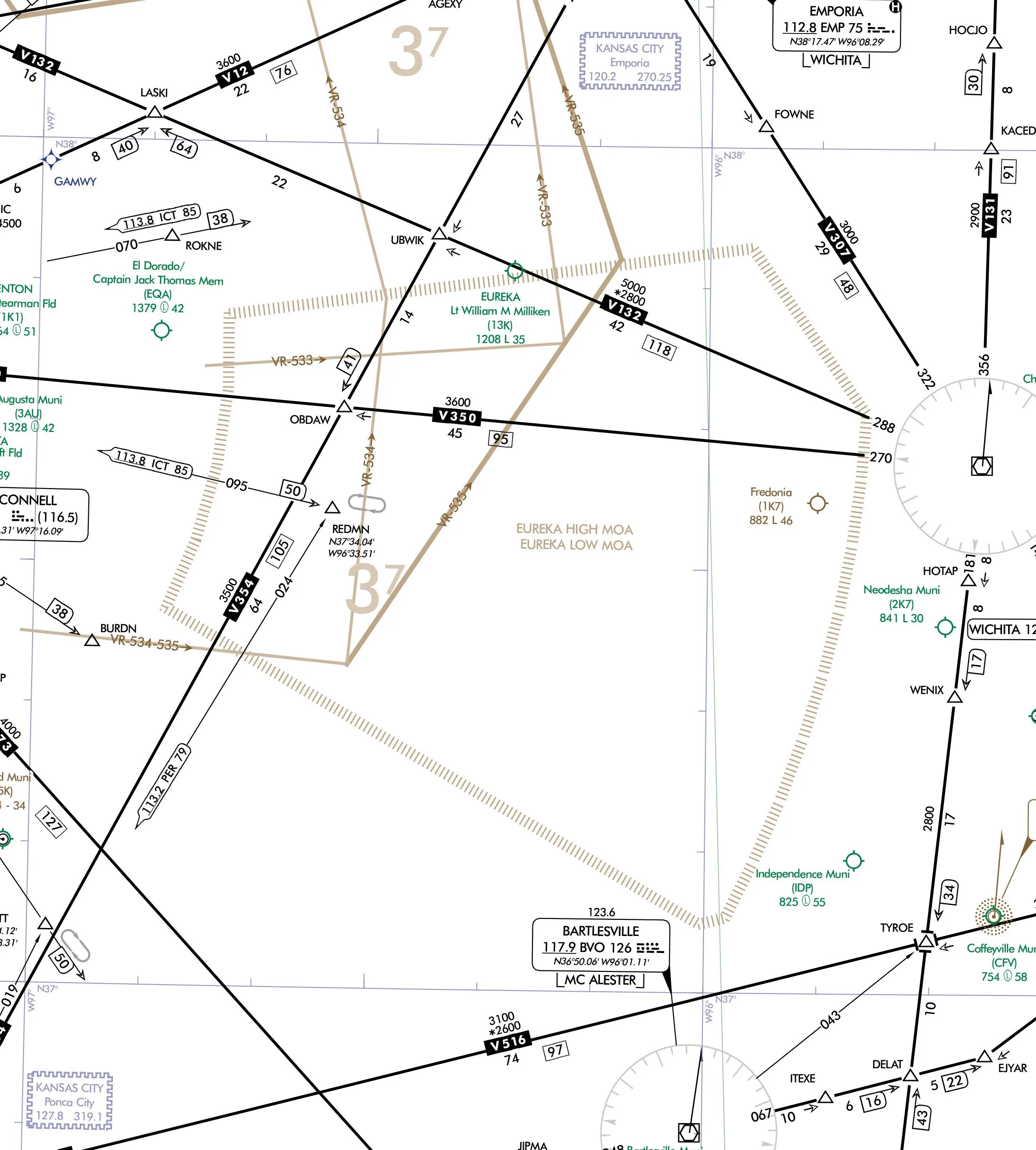

Just when you think things should start looking up, you check weather at Independence and see you need to find an approach. Sure enough, more military airspace. The ceiling’s well above minimums, but the surface winds are now whooshing, Kansas-style, from the southeast at 25 knots. Your best bet is the RNAV 17 at KIDP. It’s a simply constructed procedure, but for one small twist: The holding course reversal at UYUPU abuts the eastern boundary of the Eureka Low MOA.

Now that’s likely a non-issue since you can get cleared direct to the eastern initial fix, WENIX, then proceed to UYUPU and the final course. Thirty miles out, you ask for this and the reply is “standby”—not a good sign. Next thing you hear is something about two inbounds getting to KIDP before you and you’re to do the hold-in-lieu-of-a-procedure turn as published and await an approach clearance. And, by the way, remain clear of the MOA. Now you’ve gotta think fast to keep from being blown off the 358-degree course. (Turns out that KIDP is a busy place where a certain brand of jets is made and test flown, but this tidbit got lost in the fray.)

Then finally, a bright spot. A few miles from the fix, you’re cleared for the straight-in approach. After deftly managing the winds and the quick back-and-forth with ATC, you arrive a bit spent but glad to be on the ground after a long day. You conclude that while the system does a lot to help keep you out of Special Use Airspace, you shouldn’t just launch with a smile and hope for the best. A few more minutes of planning for extra situational awareness can go a long way to making it good day up there.