Some days you’re an ace and other days even the basics elude you. Know what you can do and what you shouldn’t do to make a landing from an approach that goes wrong.

I remember a few years ago I watched my captain try vainly to intercept the localizer. He had a good intercept angle, but the needle just wouldn’t come in. Interestingly enough, though, my HSI showed a completely different—and more reasonable—picture.

After a few puzzled moments, I realized that the inbound course for our ILS was 283 degrees but his HSI was set on a course of 330. I pointed this out. He fixed it, intercepted and flew the ILS. Yup, he’d botched the setup for the ILS, fixed it, and landed uneventfully. Only the two of us knew it. We cheated death once again.

What? Me Worry?

We should define “botched.” On a feeder route or even in the procedure turn outside the FAF, botched might mean you’ve gotten yourself completely flummoxed. But when you’re a quarter mile or a hundred feet from the MAP, straying past half-scale deflection could mean you’ve botched the approach.

But what do we mean to “save” that botched approach? Let’s go beyond simply living through the experience and making a safe landing. For our purposes, it will be starting with an error that’s outside PTS performance, recognizing it, fixing it and completing the approach as if we wrote the damn PTS.

One obvious fix to a botched approach is simply executing a missed. The mark of a pro is knowing when the approach is simply unsafe to continue, adding power, climbing and trying again. Next time around, you’ll likely execute the approach perfectly, with pride in your wisdom and judgment. But assuming you think there’s room to make a save on the current approach, you’d best have some parameters.

Botched Setup

One sure way to muck up an approach is to set it up incorrectly. That could be as innocent as setting the wrong course like my captain did, or loading the wrong approach into the navigator.

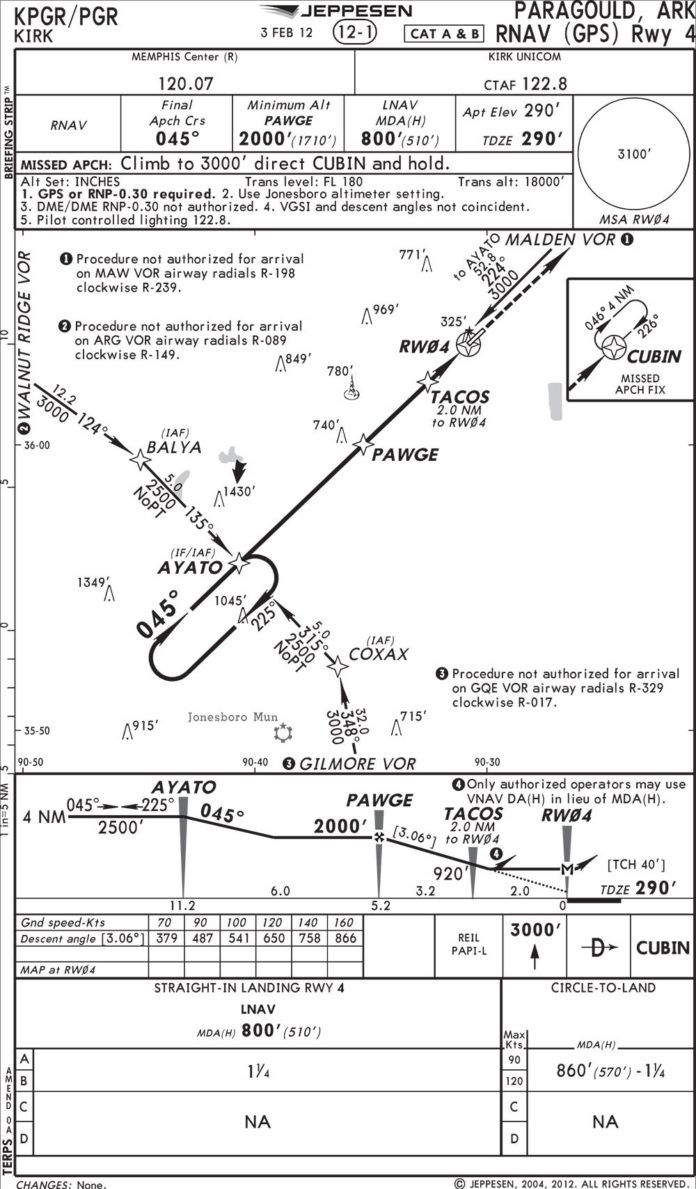

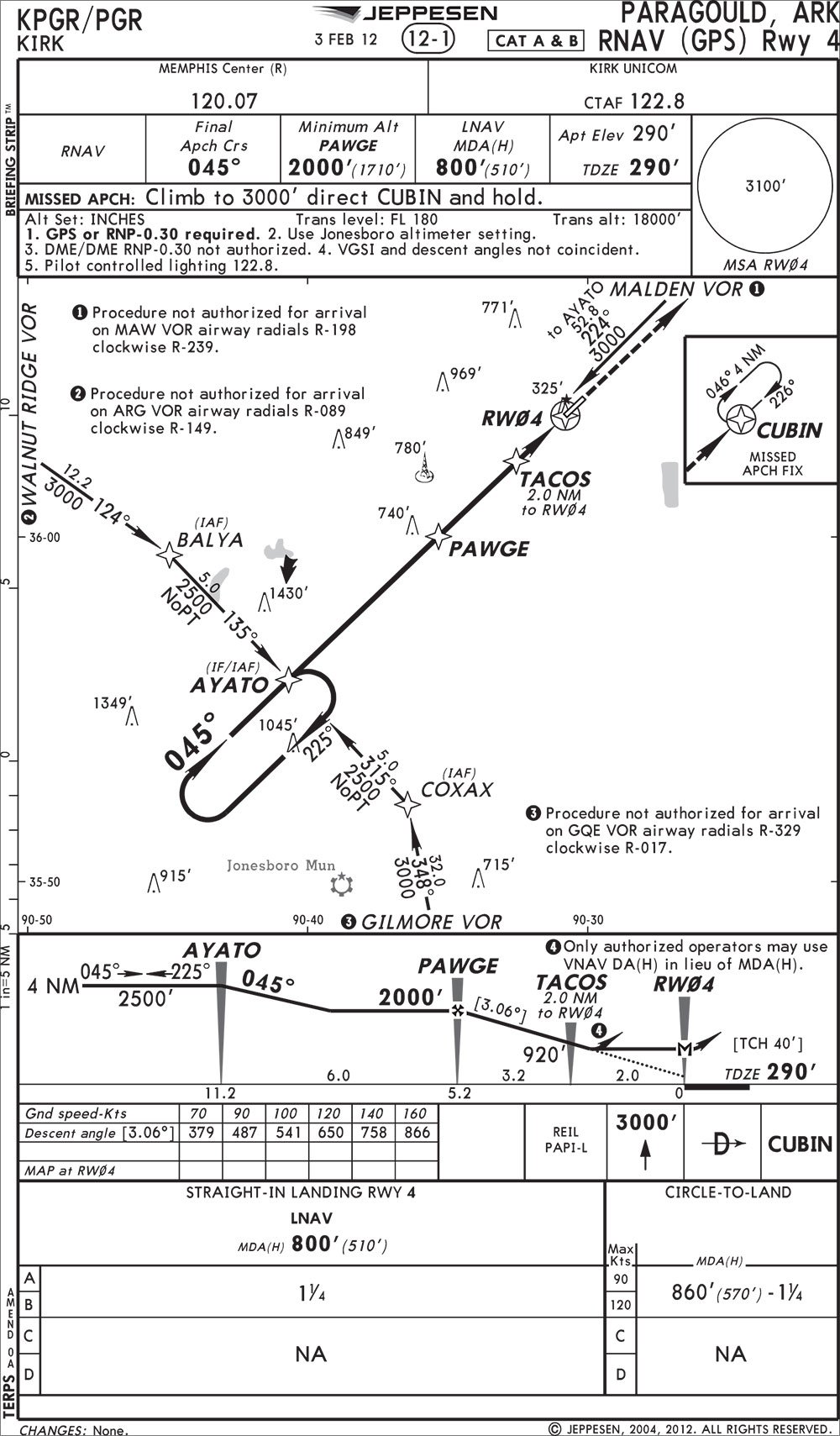

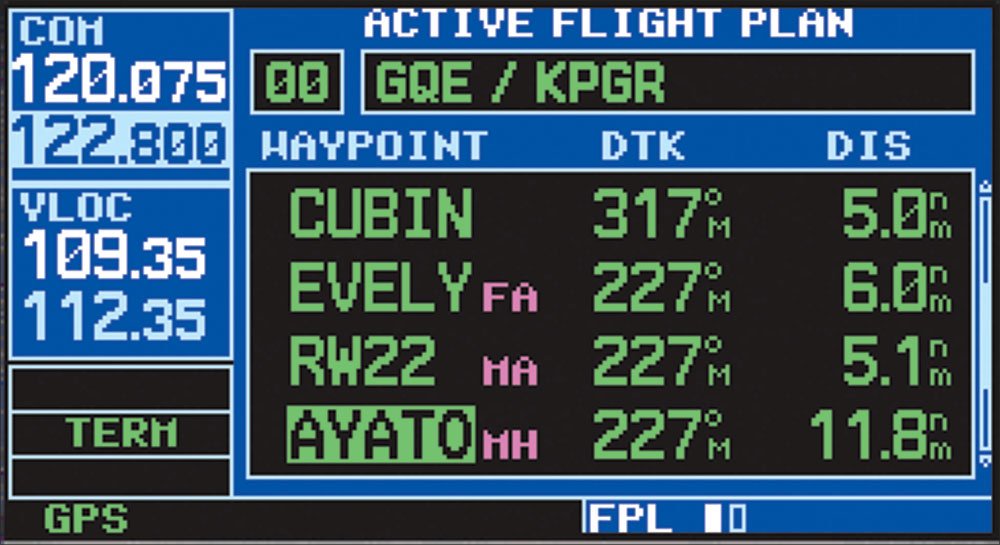

A GPS approach gives you a lot of cues, like incorrect fix names, unfamiliar courses, feeders from the wrong direction, etc. The key here is that your navigator and your HSI likely agree, but are painting you a picture that has some obvious flaws. A good error-trap for loading the wrong approach is to check the sequence of waypoints in your GPS against the sequence of waypoints on your approach chart. They should be the same names, in the same order. And the sequence of legs on the moving map should make sense for your planned arrival on the approach.

With ground-based navaids (ILS, LOC, LDA, SDF, VOR), you may have manually set the correct frequencies and courses, but loaded the wrong approach in the navigator—or vice versa. This is where your moving map and GPS are a good crosscheck. With at least one of them right, your navigator and HSI will be telling you completely different stories. You should be able to recognize that something is wrong, double-check and figure it out.

Probably the worst setup error, though, is a non-GPS approach where you set up everything correctly, but everything is ready for the wrong approach. They’ll all agree with each other, displaying a consistent, but erroneous, picture. Like the incorrect setup of a GPS approach, though, you should be able to recognize that all is not right with the world and explore why.

In both these latter cases—meaning with any approach where you manually enter frequencies and courses—a double-check of the numbers on the plate against the ones in the panel can save what would be a nasty botch. The tough part here is getting past the common human failing of seeing what you expect to see rather than what’s actually there.

If you find an error, by all means fix it. But remember that when time is short, you can ask ATC for the correct frequencies and courses, or just ‘fess up and get vectors back out for another try. (See “Your Best Laid Plans,” June 2012 IFR, for a discussion of last-minute approach changes, which is about the same as an approach-setup error.)

By George, Or Like Him

It’s basically impossible to make computer programs idiot-proof because idiots can be so ingenious in finding new ways to screw up. Back in the days when every approach was hand flown following a single needle, the idiot protection was to think through your next heading and altitude prior to crossing each fix. The automated world means your GPS and autopilot combination will do the flying, but you’ve still got to do the thinking.

Many navigators will annunciate where they’re turning next before reaching the waypoint. You should watch for these and makes sure it matches your mental expectation. At the very least, make sure you’re heads up for each waypoint to ensure the correct turn and prompt descent to the new altitude (presuming there is one).

If you have a chance to fly a plane with a fully-coupled attitude-based autopilot in some nasty winds, keep a reasonable hold on the yoke and follow what George does. You’ll most likely feel the yoke constantly pumping, correcting left-right-up-down, but in small, quick motions. The result is that the needles seem nailed to the center of the instrument. If you have old, analog needles, however, you might actually be able to see they are really, ever so slightly, wiggling all around.

If you’re having trouble keeping the needles off the pegs, you take a page from George’s playbook. When a needle is well off-center and headed the wrong way, it’s time to make corrections that are small in each increment, but continuous and aggressive.

How can corrections be both small and aggressive? Monitoring the trend is the key. If you see the needle slowly trending off the gauge, make a small correction and see if the trend has stopped. Another small, quick correction should get things moving in the right direction. By “small,” I mean two- or three-degree changes in heading or one-degree changes in pitch.

However, if it’s quickly sliding off to the peg, make several small changes in rapid succession with just a moment’s check to see if the departing needle has slowed. Now you’re back to the slow departure above and a couple more small corrections will get you back in the game.

For something like an ILS, a series of five-degree corrections is plenty for even a serious off-course trend—as long as they happen in quick succession. If you’re good, you can replace a series of small corrections with one large one, but be careful to take out a large dose of that correction as soon as the needle starts its return or it’ll run to the other peg.

Setting Limits

As we discussed above, once inside the FAF you’ve got a lot less room to fix a botched approach. If the setup is wrong at this point, go missed and start over. Essentially, you’ve set a limit that you must be configured correctly from FAF inbound or it’s simply a no-go.

If you’re just having trouble keeping the needle off the pegs, try to settle down and make proper, measured corrections. How far do you let it go and still try and make a save? That’s up to you. Outside the FAF, full-scale deflection for more than 15 seconds is probably cause for a miss. Inside the FAF, full-scale for more than three seconds might be cause for a miss. Some folks spring-load a miss at full-scale or even just three-quarters scale.

No one of these is right or wrong, but they are all one thing: objective. The point is to set a limit and stick with it. Within that limit, you can attempt a save. Cross that limit, and there’s no deliberation. It’s time to climb, clean-up and confess.

Oh, and be sure to get the course set up correctly the next time around or your first officer may write an article about you.

A Perfectly Flown Approach for the wrong runway

If you fly into airports with parallel approaches, chances are high that at least once you’ll set up, or even fly, the wrong ILS. It happens more often than you might think.

This is a subtle error to detect because there are few cues that you’ve done something wrong, especially with close runways. The vectors to final all work. The final approach course is probably the same. If the runways are truly parallel with no offset threshold, even your visual cues when you break out are about the same. This can be a huge gotcha!

But there are hints. Say the runways are 25R and 25L. You’ll almost never get vectored to 25L from the north, nor to 25R from the south. But then there’s Phoenix, shown here, which has Runways 25R, 25L and 26, just to keep things fun.

When you’re cleared for the approach, the controller usually gives you a position relative to a fix on the approach. Always check to make sure that fix is, indeed, on the approach you’re flying. Remember that the fix might not show in your navigator if you loaded vectors to final. You might have to use, you know, a chart.

If ATC lets you get far enough, the very last cue you’ll get is your clearance to land. Don’t just mindlessly parrot back the clearance. With parallel runways, always double-check that the runway in the clearance is the one you’re expecting and the one in your navigator. If it’s not, that might be a good time to execute a missed approach and even to ask for vectors to do so because the missed you loaded and briefed is also wrong. —F.B.

But This botch isn’t My Fault

Everybody makes mistakes, even controllers.

Perhaps the controller got the intercept angle wrong and you’re crossing the localizer at 45 degrees or more. Or maybe your clearance to join is simply late. It’s great if you can salvage the situation and wiggle back on course, but don’t be afraid to ask for another cut at it if you blow right through. Don’t expect an apology from ATC. This is just part of the game.

Another challenge is when you get the intercept well above the segment altitude. In my experience, a typical ILS intercept actually ends up with both needles alive, with the localizer beating the glideslope to the center by only a dot or two. But, if the glideslope is significantly leading the localizer and you were given “maintain … until” you can’t descend until that localizer comes in.

Do you dive for that glideslope or just ask for another vector? The answer depends on your comfort and the degree of error. If the glideslope needle isn’t yet full-scale, chances are you can catch it just fine, as long as you don’t get too aggressive. But if it’s solidly pegged by the time you can descend, you might be better off asking for help. The last thing you want is to dive for the needle all the way to minimums.

And remember that you’re party to this process of getting established on final. If you can see from your own avionics that an intercept isn’t going to work out, suggest one that will and tell the controller why. The 30-degree intercept shown here looks fine—until you note the winds and the actual track of the aircraft over the ground (dotted white line). It’s going to be a 60-degree intercept unless you request a heading of about 110. ATC should approve that request. It’s a rare controller that isn’t grateful for the help keeping everything rolling along smoothly. —F.B.

Frank Bowlin now sits in the left seat at work and tries not to give his first officers any fodder to write their own articles.