Kemper Aviation, a now-defunct flight school in Lantana, FL, was once clogged with over 100 young students. Some showed a lack of selfcontrol extending from their youthfully turbulent private lives on the ground upward to the skies of South Florida. Youngsters may think they are invulnerable. Most had yet to learn that invulnerability is a hazardous attitude at any age.

The school was infamous for its poor maintenance. There were so many emergency landings they became sarcastically known as the “Kemper One Arrival.” Kemper’s most senior instructor counseled younger CFI’s, “The only thing we can do is check to the extent that we can check and fly the airplanes.” Four months later, he and a student died when

their Piper Archer crashed at night due

to a loosely affixed fuel strainer bowl, invisible

from the outside, that starved the

engine of fuel.

The FAA investigated each accident in isolation from the others in its myopic way, but it’s easy to figure out why Kemper suffered six accidents and eight deaths in 14 months. Had they looked at the big picture, they would have found a superficial—at best—safety culture at work.

What is Safety Culture?

Safety culture is a set of values formed from beliefs and perceptions that employees feel toward an organization’s risks. It is felt collectively and individually; one feeds the other. Ideally, each person deeply believes the importance of safety and steadily works to increase it. It means understanding the risks of their job and how to mitigate those risks responsibly. It takes commitment, determination, and persistence.

Management sets the tone: witness the airlines where safety permeates the entire enterprise. Collective awareness forges and maintains a virtuous cycle of safety.

Since the best person to take care of you is you, cultivate a safety culture as a personal attitude. This serves a dual purpose in that it helps you become more attuned to the strengths and weaknesses of the safety cultures around you.

We cultivate safety by taking nothing for granted. Does the line crew insist on seeing your key before approaching your airplane? When able, can you monitor the fueling of your aircraft? Does the truck say 100LL or JET-A? Do they pour the correct amount into the proper tank? Do they carefully avoid deforming the fuel ports with the nozzle?

Consider that every organization, even an organization of one such as your CFI, affects you and your airplane, whether they touch it or not, as a prospective source of what the FAA calls an “organizational accident.” Or, each can potentially break an accident chain.

Signs of a Safety Culture

Professor James Reason outlines four critical components of a safety culture.

First, a safety culture is a reporting culture that encourages employees to disclose information about all safety hazards they encounter, such as reporting FOD or a near-misfueling incident via a discrepancy report or other procedure. Two-way communication between you, line workers, and supervisors is essential and propels upward to management. If you report a problem, are you confident it will be addressed?

Second, in a just culture, you see employees deciding what is acceptable. Employees should be held liable for intentional breaches of the rules but encouraged and rewarded when they provide essential safety-related information. A just culture nurtures trust.

Third, you can sense a learning culture if it uses information to improve knowledge. The best organizations learn from their mistakes and communicate safety issues. The emphasis is on analyzing events, performance, and reducing risk rather than playing the blame game.

Last, a flexible culture adapts readily to changing demands and allows quicker, smoother responses to unusual events. Do you observe no, or knee-jerk reactions, or are there well-reasoned responses? All the reporting, analysis, and learning are useless if the organization is unwilling to act with reason.

In sum, do you sense an integrity-driven safety culture? Are they on the ball? If they bolster a safety-culture attitude, you’re in good hands.

Flying in Circles

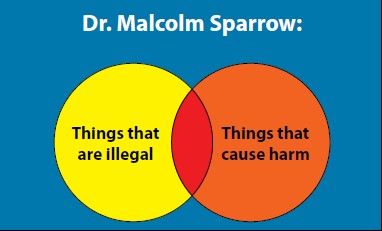

In 2009, Dr. Malcolm Sparrow, a Harvard expert in risk management, observed, “Inspectors and the aviation industry’s safety focus have been driven by the question: Is it legal or is it illegal? This is regulation-based thinking. But, simply looking to enforcing minimum regulations does not answer the question: Does it cause harm?” This shift in focus is the core of Safety Management System (SMS) thinking.

In his Venn diagram on the previous page, the circle on the left represents things regulatory. On the right, the circle represents things that are non-regulatory but can cause harm.

The overlap is those things that are both regulatory and can cause harm— traditionally, where the FAA has spent resources to meet safety objectives.

Regulations exist for everyone to mitigate hazards that affect one and all. Specific harms may apply to some groups but not others. An SMS fills in such gaps through the safety risk management process discussed below.

Is it possible to be in full regulatory compliance yet still do harmful things? Common sense provides the answer.

If you’re good with that, who can best manage those harmful things? Is it the operator such as an FBO, a charter operator or a flight school, or the FAA? Hint: Whoever is closest to the problem has the most control.

What is Safety?

To understand safety management, we need a sound definition of what we expect from that nebulous term, safety.

According to the FAA, since the U.S. began regulating aviation, “safety” has never been officially defined. Over time though, we discover a consistent relationship between concepts of risk and practical definitions of safety.

The dictionary defines safety as “freedom from harm, injury, detriment, damage, or degradation.” While this may be academically correct, it is not an especially fit definition as applied to aviation. But at least it has the virtue of linking a lack of safety to harm.

In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court said, “safe is not the equivalent of riskfree,” implying that nothing is absolutely safe, but we can minimize risk to maximize safety. Thus, the aviation accident rate can near, but never reach zero. We can quantify safety indirectly but must do so in terms of the degree of harm and how likely it is to occur. Risk management is directly actionable, but safety is not. Accordingly, we define “safety” in terms of risk management’s effectiveness and understand that risk management is one of SMS’s core processes.

Safety Management Systems

The safety culture discussed earlier is the foundation for a Safety Management System. SMS is a decision-making system for organizations, but we discuss personally-relevant elements below.

Set your safety policy. Write down personal safety objectives, perhaps flying 50 hours a year, taking an IPC twice a year and an annual Flight Review, and commit to taking online seminars. Review the instrument ACS and resolve to exceed those minimums. Read aviation magazines (especially IFR) to stay current. Review your policy occasionally to renew or update your commitments and self-imposed standards.

Manage risks in organizations that support you. How closely do they match your image of a safe operation? Can you count on individuals such as CFIs, AMTs, or organizations like an FBO or ATC to mitigate risks on your behalf? Do you need to involve your FSDO?

Promote safety. If you see something, say something. In the words of a fellow reader, “Aviation is a team activity … we all look out for each other … that’s how we improve!”

Safety Management Strategies

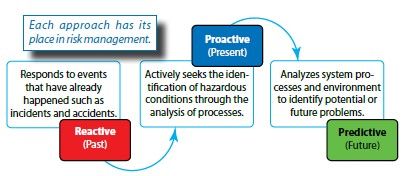

Today we incorporate reactive and proactive thinking together. The challenge is to advance to predictive thinking.

It’s common to say that we want to be proactive, not reactive. The illustration shows this is incorrect. To exclude experiences such as incidents and accidents is to deny ourselves the opportunity to learn from failures and recognize performance shortfalls. It is far better to say that we want to be more than simply reactive.

Proactive people look at current practices, seeking things out of order. You do that when you look critically at organizations in your aviation bubble. We cannot assume there are good processes in place and great people to perform them. Sometimes a look under the cowling reveals things we’d otherwise not catch.

To be predictive is to anticipate what might be heading your way. You could say that predictive begets preventive. Is there a wing strut airworthiness directive in the offing? Perhaps a regulatory change? Play the “what if” game to anticipate problems. There is a place for each strategy in developing an SMS and in real-world operations.

Airborne at night, you spot an aircraft’s rotating beacon. You turn to avoid it. Later, the fuel warning light comes on—time to land.

Few remember the man who conceived those lights and numerous other safety innovations. He was engineer Jerome Lederer (1902-2004), known aviation-wide as “Mr. Aviation Safety.”

Lederer began his career working for the U.S. Airmail Service in 1926. There he developed specifications, tested parts, and examined accident wrecks to determine their “repairability.” Here began his distinguished career in aviation safety. Countless people are alive today thanks to his ingenuity and unremitting efforts to improve safety.

In 1940, he joined the Civil Aeronautics Board (predecessor to the FAA) and directed its Bureau of Flight Safety. He was responsible for investigating accidents and rulemaking. There he developed accident investigation procedures investigators still follow today.

Several of his decisions have had a lasting impact, including mandatory flight data recorders and anti-collision lights. In 1947, he formed what became the Flight Safety Foundation. This nonprofit organization continues to circulate safety information regarding operational problems regardless of commercial interests or national borders.

In 1967, Mr. Lederer established and directed NASA’s Office of Manned Flight Safety. One of his first acts was to replace the word “safety” with the term “risk management,” reasoning that ‘’risk management is a more realistic term than safety. It implies that hazards are ever-present, that they must be identified, analyzed, evaluated, and controlled or rationally accepted.”

At NASA, he introduced the concept of systems safety engineering, meaning that safety/risk management should be engineered into systems, not layered-on after an accident.

He instituted a NASA policy of rewarding, not punishing, those who admit mistakes. Today, that notion is a principal element of safety culture.

Later in 1967, he told a New York Times interviewer, “The principles are the same in aviation and space safety. You always have to fight complacency— you need formal programs to ensure that safety is always kept in mind.”

His training as an engineer, not a psychologist, did not deter him from making keen and not always kind observations about people. “Of the major incentives to improve safety, by far the most compelling is that of economics,” he said. “The moral incentive, which is most evident following an accident, is more intense but relatively short-lived.”

In his later years, Lederer researched, spoke, and wrote about safety problems relating to human factors, including substance abuse, subtle

aspects of cognitive incapacitation, the importance of interpersonal communication, and cockpit boredom in the age of automated systems. He nonetheless espoused the opinion that automated systems could be safer than those operated manually.

To the end, he maintained that our principal nemesis is us. “The alleviation of human error,” he asserted, “whether design or intrinsically human, continues to be the most important problem facing aerospace safety.” It is the best reason to have multiple interlaced safety nets and cultures surrounding us.

And finally, he taught us, “Every accident, no matter how minor, is a failure of the organization.” Thank you, Jerry, for preventing a lot of aluminum rain.

Takeaways

Safety culture is a set of values formed from beliefs and perceptions. Cultivate a safety culture as a personal attitude. It becomes the foundation for your safety management system.

Enforcing minimum regulations does not address the broader question, “Does it cause harm?” This is the essence of SMS thinking.

Safety must be relative because absolute safety is a myth. We dynamically define “safety” in terms of risk management’s effectiveness and understand that risk management is a core SMS process. Strategically, be reactive, proactive, and predictive.

In 1901, Wilbur Wright said that “Carelessness and overconfidence are usually more dangerous than deliberately accepted risks.” That, folks, is how to avoid the Kemper One Arrival.