In 1997 the worst runway incursion in aviation history occurred in foggy weather on the island of Tenerife when a KLM 747 began a takeoff with a lost Pan American 747 on the runway. In all, 583 people lost their lives.

More recently, runway incursions remain in the news. Fortunately, there have been no accidents. The real question is how well-trained controllers and pilots can make such grievous mistakes. Let’s examine this.

A runway incursion is any incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle, or person on a surface designated for aircraft landing and takeoff.

Similarly, a surface incident occurs on a movement area (excluding runways) and affects flight safety. At tower airports, entry to a movement area including taxiways and runways is controlled by ATC. Ramps, aprons, and parking are non-movement areas.

Types of Runway Incursions

An incursion results when a pilot crosses a runway-hold marking, takes off, or lands, without clearance. If ATC clears an aircraft onto a runway while another aircraft is landing on the same runway, it’s an error against the controller. A vehicle deviation occurs if it crosses a runway-hold marking without ATC clearance.

In FY2022, the FAA recorded 1732 U.S. runway incursions of which 63 percent were pilot errors, and half were by GA pilots. In response, the FAA and AOPA are working to raise the awareness of GA pilots through online courses, videos, and quizzes.

Surface Deviations

Over 80 percent of pilot-caused runway incursions occur during taxi to the departure runway.

A surface deviation includes taxiing, taking off, or landing without clearance, taking off from or landing on the wrong surface, and deviating from an assigned taxi route. The most common incursion is failing to hold short of an assigned clearance limit, especially a runway hold marking.

In an incident at Norwood airport in Massachusetts, an aircraft holding short of the departure runway had a flat tire. The next aircraft was instructed to turn around and hold short at the next taxiway. The pilot failed to turn onto the identified taxiway. When corrected by ATC, the aircraft turned but taxied past the hold bars and onto the runway, barely missing a landing bizjet’s right wing. How can such a simple but egregious error happen?

Situational Awareness

Most incursions occur due to lapses in situational awareness. The breakdowns reflect that clearly: failure to comply with acknowledged ATC instructions, noncompliance with airport signs and markings, distractions, and failure to observe best practices, such as sterile cockpits and using aircraft lights. You can improve situational awareness with thorough preflight preparation.

Preflight

Review the airport diagram, noting any hot spots. Anticipate how you might be cleared to any appropriate runway. Review applicable NOTAMs and the current ATIS for closures, construction, and unusual airfield activities. Don’t assume your taxi route will be obvious or the same as usual.

Brief passengers on sterile cockpit procedures. Explain that their cooperation increases safety, allowing you to focus on flying the airplane.

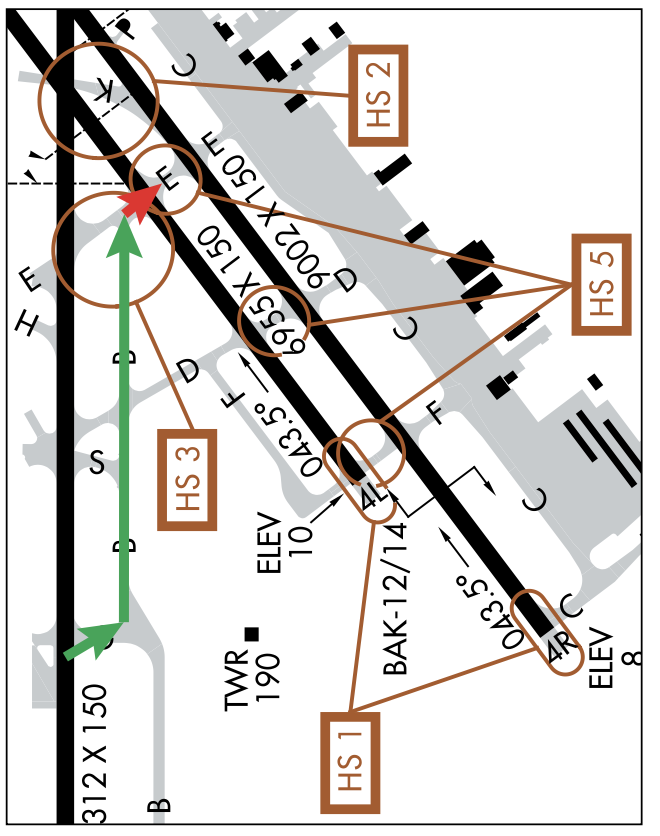

A hot spot is a location on an airport with a history of risk of collision or runway incursion, where extra attention is necessary. A hot spot is typically a complex or confusing taxiway/taxiway, taxiway/runway, or runway/runway intersection.

You can plan the safest movement path around that airport by identifying any hot spots. They are found in Chart Supplements, airport diagrams, and elsewhere.

At PHNL in Honolulu, a night GA training flight landed on Runway 8L. Taxi instructions were to turn right on taxiway Golf, left on Bravo, right on Echo, and hold short of Runway 4L. The tower later repeated the instructions, and the crew acknowledged both times. The tower’s emphasis must have indicated that 4L was in use.

Despite repeated instructions and the fact that the area between Bravo and Echo is marked as HS 3, the pilots turned from Bravo to Echo, failed to hold short, and taxied onto Runway 4L. A departing aircraft on 4L lifted off and overflew the offending airplane.

Taxi

Before you taxi, you’ll want the airport diagram—electronic or paper—handy for reference. Verify the ATIS information is still current.

Write down your taxi clearance and walk it through on the airport diagram to be sure it makes sense. Don’t start taxi until it does. Minimize head-down time and distractions while moving. Stay in the game by noting location signs and markings en route. A common mistake is to taxi too fast.

Taxi errors can create awkward situations. One hapless pilot taxied down an unmarked road at night and found himself at the Air National Guard.

Despite your best efforts, if you get lost, stop. Call Ground to ask a question or request progressive taxi instructions. Either is better than making a preventable mistake.

Approaching a runway, be sure you have clearance to cross. Visually check left and right to make sure there is no conflicting traffic. Again, if you have any doubts, reconfirm with ATC. Especially at night, some pilots turn on all exterior lights to ensure the aircraft is visible to controllers and other pilots.

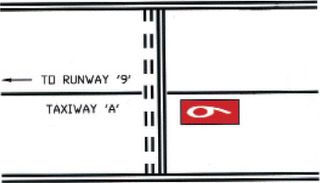

An enhanced taxiway centerline warns pilots they’re approaching a runway. It’s a series of dashed lines on either side of the yellow taxiway centerline that begins 150 feet from the runway holding position marking. You might also see surface-painted holding position markings (with a red background and white inscription) designed to supplement the hold short lines.

Hold short lines can be 300 or 400 feet from the runway due to Precision Obstacle Free Zone requirements.

Best Practices for Departure

When a line up and wait (LUAW) or a takeoff clearance is received from ATC, scan left and right to ensure the approach path and runway are clear before entering the runway. Once lined up, check your compass to ensure you’re on the correct runway.

In 2006 at Kentucky’s Blue Grass Airport, Comair Flight 5191 mistakenly departed on too-short Runway 26, instead of the longer Runway 22. The pilots would have known had they checked their heading before departure. Forty-nine people perished.

Advise ATC if your LUAW delay exceeds 90 seconds. Sometimes they’ll tell you if it will. The AIM says the risk of a LUAW accident increases after four minutes on the runway.

Under certain conditions, LUAW can be used for intersection takeoffs. Be sure to include “intersection departure” in your readback. Do not use LUAW at a nontower airport.

Turn on external lights once the aircraft is on the runway. Turn on the landing light once takeoff clearance is received, which tells everyone you’re departing immediately.

In 1991, a Swearingen Metroliner turboprop was told to taxi into position on Runway 24L at LAX for an intersection departure. A distracted controller cleared a Boeing 737 to land. The resulting accident claimed 35 lives. In 2004, a Boeing 747 passed only 200 feet above a 737 holding on the same runway. After this incident, LAX runways were segregated to allow only takeoffs or landings on a given runway.

Confirm your position before crossing the hold-short line onto the takeoff runway and again when initiating takeoff.

Best Practices for Arrival

Verify the correct runway using GPS, a localizer, runway width, lighting, or a combination. The FAA has published 12 Arrival Alert Notices to help prevent wrong surface events. See https://www.faa.gov/airports/runway_safety/hotspots/aan. They are also posted as YouTube videos.

Review your arrival taxi route as part of your approach briefing, just as you did for your departure. It should include the intended exit taxiway, runway hot spots, and how to get to parking. Consider special circumstances such as crossing other runways.

Exit the runway at the first available taxiway. Don’t turn onto a runway unless instructed to do so. Taxiing on runways can contribute to an incursion.

Don’t report clear until the entire aircraft is past the hold line. Understand taxi instructions before performing the after-landing checklist.

Summary

Most runway incursions result from a breakdown in communication with ATC, a lack of situational awareness, or controller error. Without prior planning, SA decreases, especially at an unfamiliar airport with unaccustomed or confusing markings. Distractions from passengers, interacting with an electronic device (like programming an amended clearance), and fatigue all take a toll. Weather might be a factor. The list is not all-inclusive, but the message is the same: Stay alert. The hold-short line is arguably the most critical marking on any airport.

Fred Simonds, CFII, has never had a runway incursion, but he’s come close enough that he needed to write this article.

The Tenerife accident occurred in 1977, not 1997.