I Like It, But…

I have been a subscriber for several years and enjoy each issue. My flying is mostly VFR throughout Florida, and I teach at a local flight school. I’d like to suggest that you offer regionalized versions of your magazine instead of the general issue each month.

While your content is interesting to both general aviation and the professional, it would be beneficial to offer more information for the instrument student as well. I feel the publication would better serve the readers and GA pilots if you addressed the real everyday local geography issues affecting airports and approaches.

Many pilots want to fly IFR more often but don’t quite remember how. If you addressed more of the basics and less of the quirky and obscure perhaps more pilots would actually benefit. One example would be to have a product published for particular regions or states of the country and present examples each month of airports and approaches for that particular area. This would give the local pilot community more opportunity to fly their local approaches and visit our local airports more often.

Gary Schneider

Miami, FL

While regional issues of the magazine might be appealing, we simply don’t have a broad enough subscription base to justify essentially producing multiple versions of the magazine. Like general aviation activity overall, our subscriber base has shrunk dramatically from the heydays. We have to be careful when looking at cost/benefit decisions.As far as focusing more on the basics and everyday considerations, we try to offer a mix that serves most instrument pilots. However, the magazine is targeted at, per the masthead, the “accomplished pilot.” If want something that would have more basic content that appeals to students and novices, you might consider our sister publication, IFR Refresher. Many subscribers actually get both publications to cover everything from basics to advanced topics.

Personal Mins

I generally liked your editorial about personal minimums (August), but think you missed two points.

1) The ability to fly an ILS to 200 and 1/2 is a minimum standard for an instrument pilot to pass a check ride, not something pilots should aspire to. If you can’t do this competently and confidently, you have no business flying IFR. I think of it the same way being able to hold your altitude to private pilot standards.

2) Where personal minimums should come into play is in decision making. I would hate to think that a pilot might intentionally miss an approach other than at published mins and the published missed approach point and then run out of fuel trying to find better weather. If you start an approach, you should always fly it to the lowest available minimums because that is the safest thing to do. However—in the decision making process—if the weather is below our personal mins, we shouldn’t plan a flight there. That is, don’t take off on the flight, or plan an early diversion to someplace with better weather. En route and can’t find a better option? Fly the approach to the published minima.

The whole notion of an early missed approach doesn’t even consider that the missed approach procedure starts at the missed approach point. For example, turning early on many ILS approaches might take you into higher terrain; starting your climb early, even straight ahead, on the KVNY ILS Z 16R is a no-no due to a climb restriction that keeps you clear of the KBUR ILS 8.

Kenneth Adelman

Corralitos, CA

When To Leave Final

I have been an avid reader of this publication for years now, beginning with my instrument rating and through my CFII. Now, IFR Magazine is one of my favorite reads on my airline commute from my home in St. Louis to my airline base in LAX.

Airline pilots rarely get anything but vectors to an ILS. Even more rare with GPS approaches are VOR approaches. I still stay sharp on these non-precision approaches, however, thanks to my /A-equipped 1970’s Piper Cherokee.

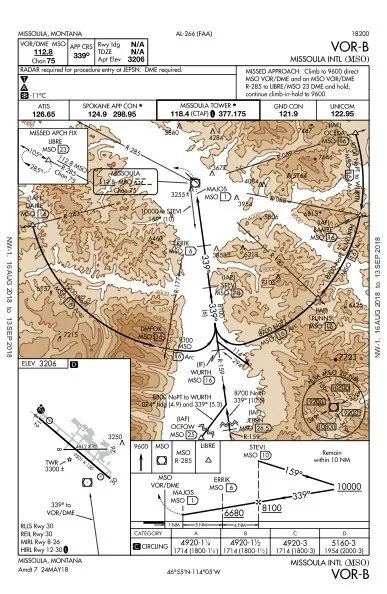

In the training for the airline, we frequently fly the VOR-B into Missoula, MT. It’s a fairly straightforward approach, honestly. However, the descent rate after the final step-down fix (ERRIK) to the runway is quite steep to land straight in on Runway 30, even if a left base entry is made—about 3400 feet of altitude in about 6 miles. That six-degree descent rate wouldn’t meet our stabilized approach criteria. Flying a left base makes the descent rate barely manageable.

Let’s say the ceiling is at 4000 feet and we have the requirements of 91.175 met. When are we legally permitted to leave the final approach course (FAC), enter a left base, and begin final descent? Could we legally leave the FAC before ERRIK?

The airline pilot in me says that legally, a circling approach is a visual maneuver and it’s technically legal to leave the FAC when you have 91.175 met. The CFII in me says that leaving the FAC outside of the TERPS circling radii is silly and possibly dangerous.

In the jet it’s a catch 22. If we leave the FAC early, we can safely maneuver the airplane and be stabilized for an easy landing on 30 while maintaining visual terrain clearance (this is what they teach). If we stay on the FAC too long we risk either missing the approach or getting pressured into an unstable descent.

I’m not ruling out the technique that I’d do in the Cherokee, which is to fly the FAC over the threshold and enter upwind for a full left-traffic pattern. It’s just a more difficult maneuver in the jet.

The regs have all sorts of guidance on when it is legal to leave the vertical profile of an approach. However, I can’t seem to find any guidance on when it is legal to leave the lateral profile, i.e. the final approach course.

Justin Kunz

St. Louis, MO

We sent this over to Mark Kolber, our regs guru, and he replied:

There’s no reg on when one can maneuver away from the FAC, and no formal General Counsel interpretations I’m aware of. But there is some related guidance in the Instrument Flying Handbook. Note the last two sentences:

“The circling minimums published on the instrument approach chart provide a minimum of 300 feet of obstacle clearance in the circling area. During a circling approach, the pilot should maintain visual contact with the runway of intended landing and fly no lower than the circling minimums until positioned to make a final descent for a landing. It is important to remember that circling minimums are only minimums. If the ceiling allows it, fly at an altitude that more nearly approximates VFR traffic pattern altitude. This makes any maneuvering safer and brings the view of the landing runway into a more normal perspective.”

This is definitely not a legal opinion, but that tells me the obvious. The purpose of an IAP is to get you in position to make a normal landing and, the more normal the better. With your 4000-foot ceiling, I think we are in the neighborhood where some of the cases I listed in the circling article and the FAA’s recent guidance on traffic patterns pretty much require IFR traffic to fit into the VFR traffic pattern. I’m not sure how you come to the conclusion that circling with a 4000-foot ceiling is potentially unsafe. I’d think exactly the opposite. —MK

We read ’em all and try to answer most e-mail, but it can take a month or more. Please be sure to include your full name and location. Contact us atIFR@BelvoirPubs.com.