Stabilized Approaches—Bah!

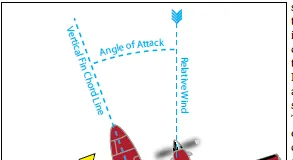

Well, I guess you and the FAA will have to spank me. The stabilized approach is just a technique. Some pilots do not believe in this concept and fly decelerating final approaches for a specific reason—better energy available.

Kinetic energy ( MVV) goes up with the square of the speed. Double your speed and you have four times the energy. More energy available will let you fight Mother Nature with a chance for a better outcome.

I once had the opportunity to train some Aussies in the T-38. Max gear/flap speed was 240 KIAS, and they just zipped around on approach at 240 right up to glideslope intercept, dirtied up the “sugar rocket” set power to hold the eventual final approach speed and slid down the glideslope as speed bled off to the final value just before power reduction for landing.

Those of you flying pistons, have probably heard “keep power on in the pattern”? The old days of going idle on downwind and gliding around the pattern are pretty much gone. Historically, piston engines quit more at idle than at a higher power setting. Some POHs also say to fly a higher speed if using the autopilot for better servo authority.

Staying on glideslope with a varying VVI is also a good hand-eye exercise for many but a no-brainer for those who can do the math involved. For many of us who fly the” little guys” to long runways on the ILS, keeping speed up makes for a better missed energy level if needed—and also lowers the rental Hobbs time. Some commercial operators wait until first downward movement of the glideslope to dirty up and fly the initial part of the glideslope in a decelerating fashion—after all, they work for a profit.

By the way: Don’t drink with the Aussies—they are professionals.

Richard “Dog” Brenneman

Vacaville, CA

Actual Conditions Indeed

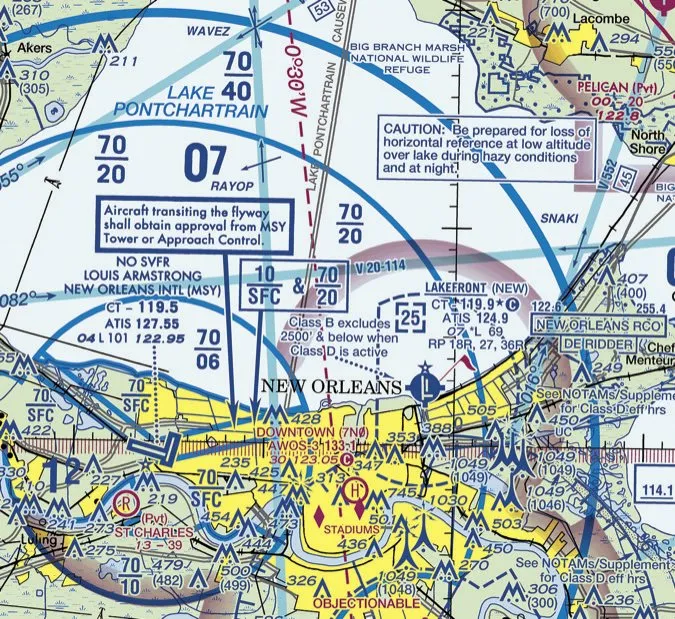

Anyone who’s flown into Lakefront Airport in New Orleans (KNEW) on a muggy summer night probably chuckled while reading Mark Kolber’s excellent article “‘Actual’ Conditions” in the December issue. If you’ve been vectored out over Lake Pontchartrain at night for Runway 18, the FAA all but admits you’re in “actual instrument flight conditions” with its warning on the sectional chart: “CAUTION: Be prepared for loss of horizontal reference at low altitude over lake during hazy conditions and at night.”

I’ve never logged an approach in that instance, because by the time you’re at the FAF for Runway 18, even on a hazy night you can typically see New Orleans lit up in all its glory. But a couple of times I’ve logged 0.1 actual tracking northbound over the lake at night. That warning is there for good reason!

Scott Humphries

Houston, TX

Likes Paper

Regarding “The Checklist We Want” in December, I have always preferred the simplest of systems which has served me for two decades. This consists of a vinyl envelope-protected two-column, back-to-back paper checklist (edited/generated in Microsoft Word) with a side-mounted paperclip. I simply advance the position of paperclip to the corresponding item as I progress through the checklist. The checklist is on my kneeboard.

The system is—ahem—highly energy efficient so there is no concern with battery depletion whereas your image #2 shows 43 percent remaining on your IPad battery at presumably the start of your flight (i.e. you are in the climb portion of your checklist). One last advantage is its resilience to “input” errors during turbulence compared with a touch-screen system.

Douglas Boyd

Houston, TX

Clearly, high-tech solutions to age-old processes aren’t for everyone. If you’re using something that works well for you, as you are, stick with it. For me, it was as I said in the article—I’d gotten spoiled by a challenge-response verbal system with a copilot and I wasn’t making sufficient use of traditional text checklists (paper or otherwise) in the air. MiraCheck works well for me.I know you were joking, but others might have wondered; the percentage of battery remaining on the iPad was purely a result of normal daily use and taking images while working at my desk, probably late in the day. It’s not an indication of real-world battery life on a typical flight. —FB

Quiz Nits

I have a couple comments on December’s quiz.

In question 2, while in 91.103 “vicinity” is not defined, it is defined for the purposes of weather reports and forecasts. For TAF: In the United States, vicinity (VC) is defined as a donut-shaped area between 5 and 10 SM from the center of the airport’s runway complex. AC0045H I interpret VC meaning anywhere within a 10 SM radius of the field.

Question 11 notes that TAFs are good for 24 hours. However, some international airports issue TAFs further out. Notably, Boston is 27 hours, Atlanta is 28 hours and Los Angeles is 30 hours.

Luca Bencini-Tibo

Weston, FL

Altimeter Setting, Where?

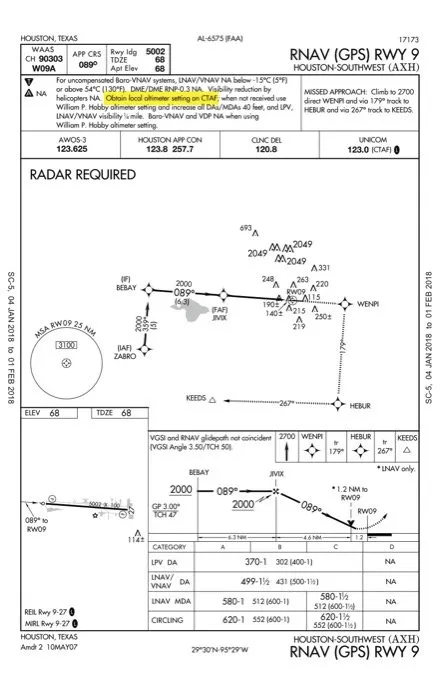

Just read “Altimeters on Approach,” (December) and it reminded me of a situation I ran into just yesterday. I was flying to Houston Southwest airport (KAXH) from the north in crummy weather, with forecast winds favoring Runway 9. The notes to the RNAV Rwy 9 approach say “Obtain local altimeter setting on CTAF; if unavailable use William P. Hobby altimeter setting…” etc.

But the same chart identifies the frequency for the KAXH AWOS, which was broadcasting the local altimeter setting at KAXH. What’s up with that? Just a snafu? By the time I got there, the weather was much better than forecasted so it mattered not. But I was set up using the setting from the AWOS.

Phil Bruns

Shiro, TX

Lee Smith, our resident TERPSter, concluded that this is a charting artifact from before the AWOS was commissioned, and it should have been removed. The formal airport record shows the AWOS as the official altimeter source. Later, we reached out to our friends at the FAA charting office and they confirmed Lee’s conclusion. Watch for an update removing that note.

We read ’em all and try to answer most e-mail, but it can take a month or more. Please be sure to include your full name and location. Contact us at IFR@BelvoirPubs.com.