The cornerstone of aviation communication is the read back/hear back loop. As an air traffic controller issuing hundreds of instructions daily, ensuring each one is both understood and executed is just another part of my job.

Unfortunately, many pilots play loose with read backs. A little sloppiness is expected from students, but every day, we encounter pilots driving everything from airliners and corporate jets to military fighters that aren’t giving us the responses we need on the radios.

Perhaps it’s just a lack of awareness of the rules, or a casualness borne of familiarity. Whatever the case, it can be frustrating to lean on pilots for read backs of common instructions.

Good read backs benefit the pilots themselves. When pilot-controller communication is incomplete or vague, it creates a distraction at best, or—at worst—true potential for disaster. Keeping your communications clean adds safety. Achieving that clarity only takes a little bit of time and discipline.

Identity Crisis

On any given day, per National Air Traffic Controllers Association statistics, there’s an average of 87,000 flights over the U.S. Dozens of these pilots may be on the same ATC frequency. They could be dodging weather, descending into complex terminal airspace, or conducting military operations. Perhaps they’re just out for a sightseeing flight or training. As they fly, they’re checking in, replying to instructions, taking frequency changes, and making requests.

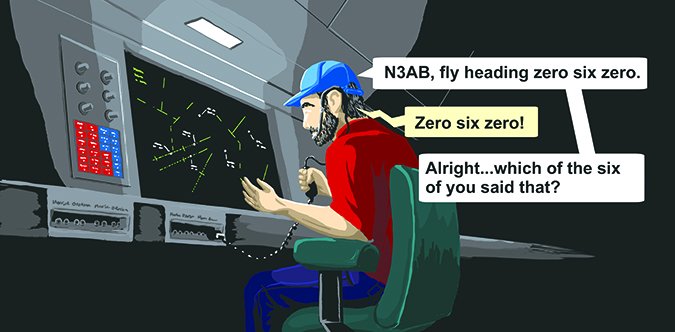

That’s a lot of voices on the radio. How can ATC tell which one is you? More specifically, when ATC issues you an instruction, how can they know—with certainty—that you, and you alone, are the one acknowledging?

Your call sign, of course. Per AIM 4-4-7.b.1, “Include the aircraft identification in all read backs and acknowledgments.” It’s so ridiculously simple, but so crucial. It’s also distressingly infrequent, not just from students, but from highly experienced aviators.

Imagine I tell you, “N3AB, fly heading zero six zero.” All I hear as a response is, “Zero six zero.” Okay, well, was that you? Was it your copilot, student, or instructor? Or, was it another aircraft entirely, that is now unintentionally turning to a 060 heading, potentially causing havoc and conflicts? Now I have to use valuable time clarifying, “That last transmission was for N3AB only. N3AB fly heading zero six zero.” And, of course, I wait for the second read back.

Get in the habit of ending each transmission with your call sign. As AIM 4-4-7.b.1 continues, this “…aids controllers in determining that the correct aircraft received the clearance or instruction. The requirement to include aircraft identification in all read backs and acknowledgements becomes more important as frequency congestion increases and when aircraft with similar call signs are on the same frequency.”

Tarrance Kramer

On the Numbers

When ATC issues you an instruction, what part of it are you absolutely, legally required to read back? Answer? Not nearly as much of it as you might think.

In AIM 4-4-7.b, “Pilots of airborne aircraft should read back those parts of ATC clearances and instructions containing altitude assignments, vectors, or runway assignments as a means of mutual verification.” Note it says “should,” not “must.” Per the FAA’s Plain Language Program Manager, Dr. Bruce V. Corsino, “‘Must’ is the only word that imposes a legal obligation on your readers to tell them something is mandatory.” Therefore, if you should do something, it’s considered a strong suggestion, not an obligation.

Let’s say I give you an IFR clearance: destination, route, altitudes, frequency, and squawk. You could just say, “N3AB, roger.” You’re not required to read back any of the specifics. If I assign you heading 180, you could reply, “N3AB, wilco.” The same with altitudes, speeds, routing changes, and other critical things.

Controllers are aware of this. FAA Order 7110.65—the ATC rule book—plainly states under 2-4-3 Pilot Acknowledgement/Read Back, “…pilots may acknowledge clearances, control instructions, or other information by using ‘Wilco,’ ‘Roger,’ ‘Affirmative,’ or other words or remarks with their aircraft identification.”

There can be a big gulf between legal and safe. Maybe the controller misspoke. Maybe you didn’t hear it correctly. I’ve given a bad altitude or a bad vector, and only caught it when the pilot’s read back didn’t sound right. What if the pilot had just responded, “N3AB, wilco.”? I’d have never caught it until I saw the aircraft doing something unexpected.

So, here’s my recommendation: read back at least the numbers—altitudes, headings, speeds, frequencies. AIM 4-4-7.b backs this up: “The read back of the ‘numbers’ serves as a double check between pilots and controllers and reduces the kinds of communications errors that occur when a number is either ‘misheard’ or is incorrect.”

It doesn’t have to be fancy. Imagine I tell you, in glorious ATC phraseology, “N3AB, fly heading two one zero, descend and maintain two thousand.” Sure, you can read it back verbatim. Or, you can just say, “Two one zero, two thousand, N3AB.” The digits are the most important part. Per AIM 5-5-2.b.4, my controller responsibilities include ensuring “that read backs by the pilot of altitude, heading, or other items are correct. If incorrect, distorted, or incomplete, [I must make] corrections as appropriate.” Give me and my coworkers that opportunity to fix it if it’s wrong.

Cover Your Assets

The lack of read back requirements on the pilots seems counterintuitive to controllers. I’m required to be accurate, working with questionable information? It’s a little disconcerting.

For us, it becomes a liability issue. Say I assigned you that 210 heading, and you reply, “N3AB, wilco,” but flew 310 instead and had an incident. Sure, you’d get some of the blame. But, I’d get my share for not catching your mistake. That’s why so many controllers insist on read backs that aren’t technically required by the reg books. We’re protecting ourselves. But, we’re protecting you, too. Sure, if you crash we look bad, but you can look, well, dead.

A controller I know taxied a Bonanza to the active runway. The pilot didn’t read back the runway assignment. He ended up crossing the hold short line on to the runway, disappeared off all frequencies, and just sat there for minutes. Tower had to send multiple aircraft around, including a Boeing 757. The Boeing probably burned the Bonanza’s weight in fuel on his go-around.

The Bonanza screwed up and was tagged with a runway incursion. However, my friend also got chastised for not ensuring the guy properly read back the runway assignment and taxi instructions. Note that AIM 4-3-18.a.9 says: “When taxi instructions are received from the controller, pilots should always read back… the runway assignment.” This is paralleled by AIM 4-4-7.b.4 and 7110.65 2-4-3: “Initial read back of a taxi, departure or landing clearance should include the runway assignment, including left, right, center, etc. if applicable.”

Again, those regs said “should,” not “must,” so nobody broke the rules. However, that’s a textbook example of how meeting minimum legal requirements doesn’t always translate to safety.

Had my friend gotten a good read back, the pilot might have been more aware of his surroundings. Even if he still busted the runway, there’s nothing the controller could do. Needless to say, my friend now demands read backs on all runway assignments—once you get burned, you stop playing with matches.

Hold It, Shorty

So, what are absolutely required? Runway hold short instructions, for one. Under the AIM’s Section 5, Pilot/Controller Roles and Responsibilities, paragraph 5-5-2.a.1 says a pilot has a responsibility to “Read back any hold short of runway instructions issued by ATC.” That’s non-negotiable, isn’t it? After all, who would want anyone entering a runway without permission? There couldn’t be any contradiction to that, right?

But AIM 4-3-18.a.9 Taxiing, says: “When taxi instructions are received from the controller, pilots should always read back: (a) The runway assignment. (b) Any clearance to enter a specific runway. (c) Any instruction to hold short of a specific runway or line up and wait.” Again, “should,” not “must,” implying that hold short read backs are recommended, but ultimately optional.

But wait… there’s more! AIM 4-3-18.a.9 adds: “Controllers are required to request a read back of runway hold short assignment when it is not received from the pilot/vehicle.” We also have 7110.65 2-4-3.b telling controllers, “Ensure the read back of hold short instructions, whether a part of taxi instructions or a LAHSO clearance.” Then, there’s the note on the airport diagram as shown on the previous page.

A hold short read back is therefore mandatory. If I tell you to hold short of the runway, and you don’t give me that read back, I may have to declare the runway unsafe and not let anyone use it. That’s my obligation to everyone’s safety.

This illustrates the conflict between the language and the spirit of the law. I highly recommend you treat “should” in the AIM as a “must.” Assigned a departure runway and a taxi route? Read ’em both back. Told to cross or taxi on a runway? Read it back. Cleared to land or takeoff from a runway? Read it back. Hold short of a runway or taxiway? Please read it back.

Effective read backs take mere seconds, and ease a lot of concerns. Remember the key elements: your call sign, any numbers, and any runway instructions. It gives us both a chance to catch anybody’s errors, and creates a safer environment for you and all the pilots around you.

Tarrance Kramer and his fellow controllers really appreciate great read backs. So much so, that when they hear how great you are on the radio, you might get that special request you made.