Going IFR is definitely a great way to navigate to busy airports. Filing trims workload; the script’s in place for airspace, navigation, traffic and much of the weather, ’cause you’ve planned ahead. But the system doesn’t remove all the surprises, especially when traffic starts piling up.

The Fine Print

At least you’re starting with a solid flight plan. As it’s unlikely anyone will get direct from Juneau, Wisconsin to the Twin Cities, you’re doing some homework. The destination is St. Paul South-Fleming Field, where you and a couple of friends will pick up a rideshare to the Mall of America. The direct-to runs right along the southern length of a MOA, over a Class D military airport, and a Restricted Area. You play defensive and file to go around all of that while including outbound, enroute and inbound checkpoints: RANDO DLL HERMNN WEASL

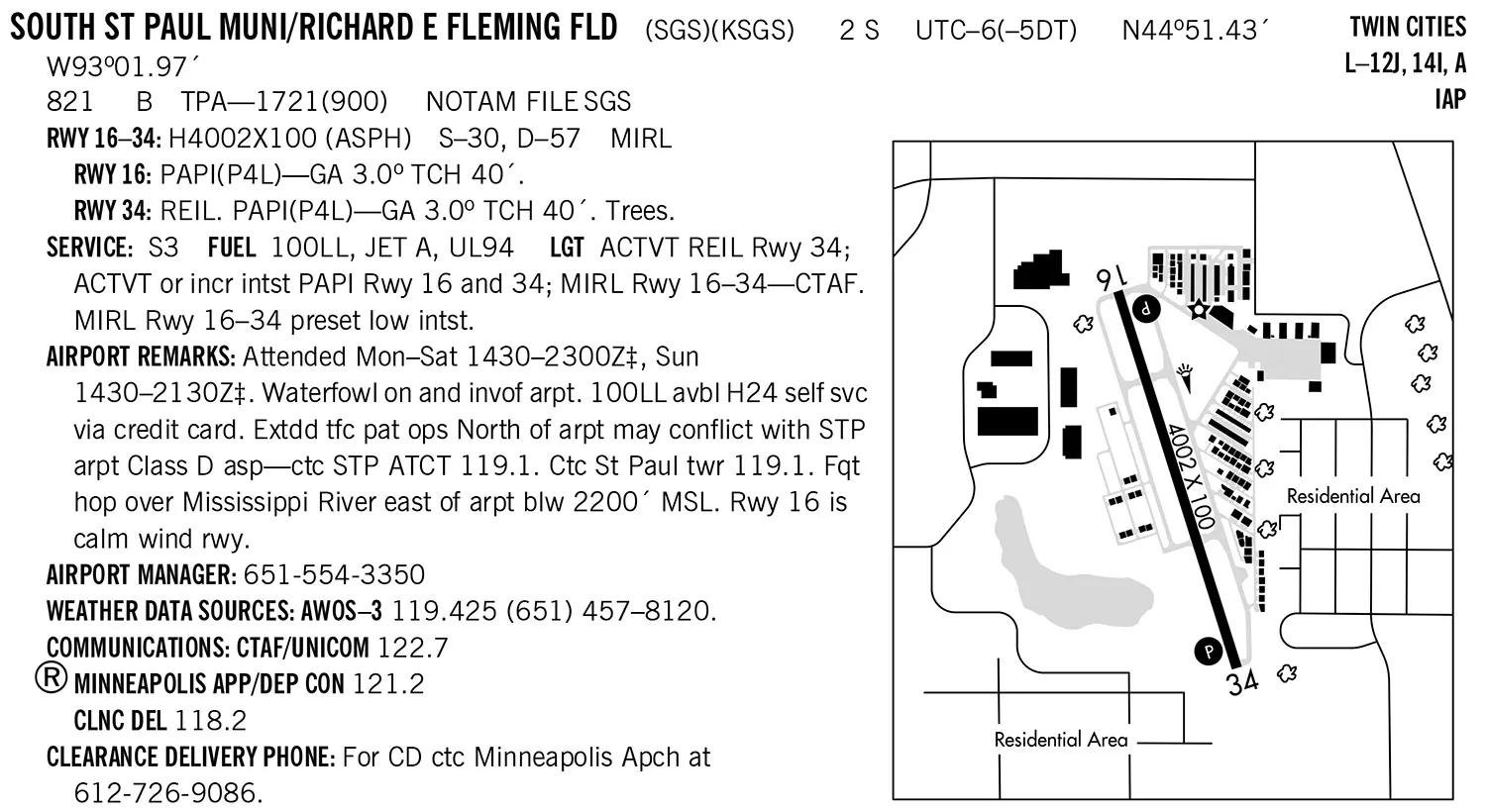

Wrapping your head around Fleming Field takes more digging beyond the the EFB. Like most fields near a major hub, KSGS gets loaded with local traffic and flight training. Meanwhile, to the north is the other St. Paul airport—Holman Field (KSTP), with a Class D ring close enough to require some local procedures. Those are partially explained in the Chart Supplement, with more details from the “Recommended Arrival and Departure Procedures” posted online and at the FBO. Now, you wouldn’t have known about those, but you called to ask about tiedowns. The main caveat for KSGS is the risk of conflicts with aircraft flying instrument approaches to Runway 32 at KSTP. So the local procedures keep traffic patterns compact, using the landmarks provided.

Wrapping your head around Fleming Field takes more digging beyond the the EFB. Like most fields near a major hub, KSGS gets loaded with local traffic and flight training. Meanwhile, to the north is the other St. Paul airport—Holman Field (KSTP), with a Class D ring close enough to require some local procedures. Those are partially explained in the Chart Supplement, with more details from the “Recommended Arrival and Departure Procedures” posted online and at the FBO. Now, you wouldn’t have known about those, but you called to ask about tiedowns. The main caveat for KSGS is the risk of conflicts with aircraft flying instrument approaches to Runway 32 at KSTP. So the local procedures keep traffic patterns compact, using the landmarks provided.

Would going IFR as planned help? There are only an RNAV and a localizer, both to Runway 34. With winds southwest at five knots, you might need to go with traffic and circle to 16, the designated calm-wind runway. “Calm” here is six or fewer knots. A slight tailwind is not an issue for your light four-seater landing on 4000 feet, but you’d prefer a straight-in approach. Circling does have additional considerations.

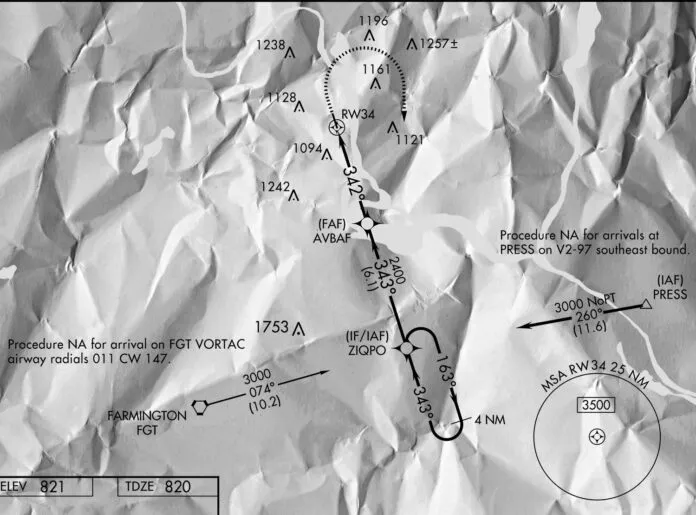

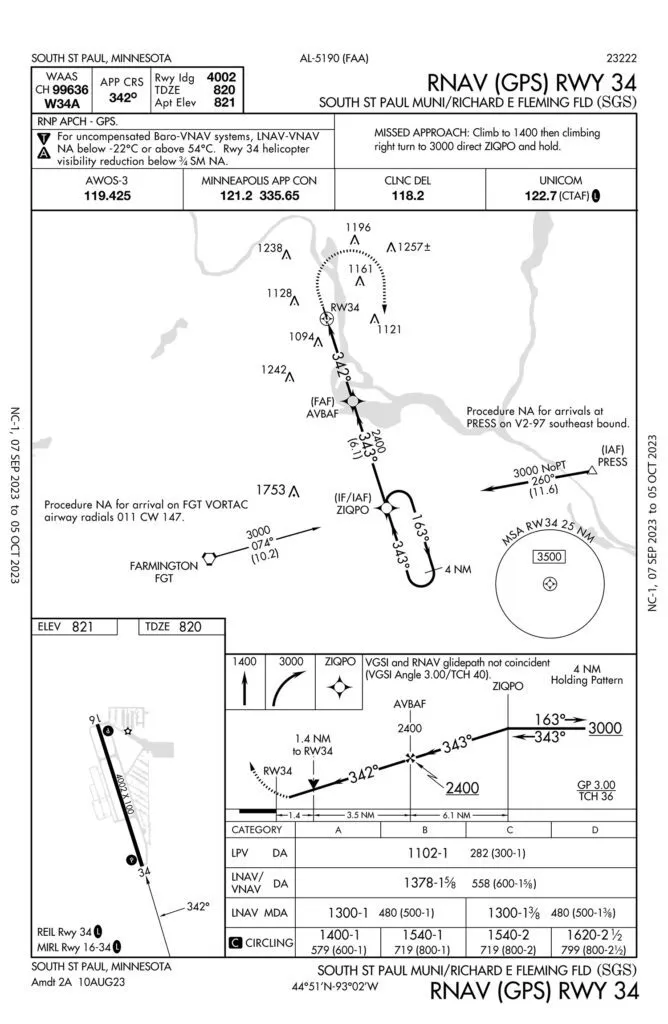

Unless … maybe, if you can verify there’s no traffic conflict, VFR or IFR, you get a straight-in for 34. That could be the case with pre-departure weather there showing 900-3. Either way, the arrival will start out the same coming from the east: PRESS, 3000 feet. At ZIQPO, which can also be the IAF if you prefer, turn to an 11-mile final. The alternate can’t be Holman Field due to the weather, so use Rochester 61 NM to the south. But of course, if you actually need an alternate you can get cleared to Holman via the RNAV 32.

Brief Some More

Now, brief each runway. If you can go straight-in for 34, the LPV minimums are 1102-1 and there’s a VDP at 1.4 NM. Given the ceilings, you’ll likely break out closer to a two-mile final. You’ll be on the CTAF to monitor traffic. If flying the missed (“climb to 1400 then climbing right turn to 3000 direct ZIQPO and hold”), Minnie Approach will coordinate with the nearby D and, when above 2300 feet, the overlying Class B.

So you turn your attention to the many obstacles early on the missed approach. They’ll be invisible as you climb into the clouds, so be sure to stick to the course and verify climbing through 1400 feet before turning. That altitude also happens to be the circling MDA.

The VDP will also be a good place to confirm all is well with continuing—your personal circling minimum vis is three miles. And you want to be clear of traffic, heard or seen. Any doubts? Go missed while still on the inbound course to 34 and fly the published procedure. If it looks good and you continue for the circle, stay at 1400 feet as you step over to the left downwind.

What if you’re circling and there’s popup traffic, or a runway obstruction? From the downwind for 16, you can intercept the missed-approach course over the runway, but note that the traffic pattern altitude for light aircraft like yours is 1720 feet, or 900 feet AGL. If someone’s out there where they shouldn’t be, you’ve simply got to get higher. If you must go around after entering base or final for some conflict, or if the tailwind has you going too far down the runway, keep circling at MDA. It’s your airspace until you cancel. But realistically, you can’t safely get back to the missed approach without circling back to it. Oh, and how comfy are you anyway flying 600-foot traffic patterns? That’s what this is in disguise. If you’re not, use 34 or divert if need be.

If you miss, will you try again? If it’s for a correctable approach error and the weather is okay for another try, request vectors. If you miss ’cause the weather’s down, and/or you decide not to circle, divert to the other St. Paul. All those what-ifs likely won’t come up, but this circling stuff requires some thought.

Join the Party

Off you go and by the time you’re in Minnesota, it’s time to pick up the local weather at KSGS on com 2. Wow, it’s up to 1200 scattered, visibility five miles, and winds are from 010 degrees at seven knots. You give Approach a heads-up on a possible circling approach and monitor the CTAF. Someone’s departing straight-out from 16, probably IFR. Then you hear a Skyhawk on downwind for 16. Then a Citabria, departing 16 for left closed traffic. And yet another, a helicopter, two miles east at 600 feet. Now that airport remark “Fqt hop over Mississippi River east of arpt blw 2200’ MSL” makes sense. After spending the last few weeks sitting at Juneau cancelling or delaying flights due to low weather, it’s ironic that just this once, you would’ve preferred the weather stay IFR as the higher ceiling put a wrench into your lovingly briefed approach plans.

Okay, so the wind went up past six knots, but that must be the crosswind component as everyone’s still on the calm-wind runway. No time to split hairs now, you’re cleared to ZIQPO at or above 3000 feet, and cleared for the RNAV 34, circle-to-16, followed by a change to advisory to talk to the other aircraft. By then the heli has passed, leaving the two in the pattern. And then you hear a twin waiting at 16, talking to the others about waiting for an IFR departure. Of course, he’s waiting for you.

The clouds keep breaking up and while they’re lower over the airport, it’s nearly clear southeast of the field. Do you help out the twin and cancel, then step over to downwind, or get re-cleared for the visual to shorten the approach, or just keep going? You’re still at 3500 feet anyway. In fact, you stay there for a few minutes as you weigh the options, knowing there are still several miles to descend to the final fix and you’re by no means a speedy single.

By ZIQPO, you’re at 3200 feet, with only 800 feet to descend in the six miles to AVBAF. With a clear view of the field now and a good 10 minutes ’til touchdown, you figure it’s good for a cancel. Approach, also spring-loaded to release the twin, quickly acknowledges and you’re back on advisory, squawking 1200 but still following the approach path. You inform the twin you’ll step east at AVBAF and watch for him. The pilot thanks you and heads south. By then your GPS had been flashing an airspace message, and you’ve been wired to ignore these flying IFR. But now, you’re VFR, and didn’t really plan for it. So now you see it—AVBAF is right in the middle of the 3000-foot Class B ring, which you missed by maybe 50 feet … maybe. By the time you enter downwind and catch your breath after that airspace hiccup, it’s just a normal VFR pattern to 16. But this wasn’t at all a normal arrival, and it just goes to show that good briefings cut down on workload, but not always the surprises.