The Beechcraft Baron was descending out of 4000 for 3000. “I’ve got the airport in sight.” All the weather displays in my approach control radar room showed beautiful VMC everywhere. The Baron was on a vector for a visual approach to one of our local airports.

“Roger,” I said. “Fly heading 270 for sequence. Expect about a five-minute delay. I’m awaiting IFR cancellation from a King Air who appears to be on a four-mile final for Runway Niner, descending out of 2000.”

“I’ve got visual on the King Air,” the pilot declared. “Requesting lower.”

He’d requested a visual approach. The weather was VFR. The Baron had his preceding traffic and the airport in sight—all set for a visual approach, right? Well, there was just one thing: the airport they were flying into didn’t have an operating control tower.

What kind of difference does that make? A huge one, as it turns out.

Airport vs. Runway Clearance

Many pilots still call fields without a control tower “uncontrolled airports.” That’s not quite accurate. Sure, VFR planes can come and go as they please from such airports. However, if a plane is IFR, ATC still has oversight over its arrival or departure from that airport. “Non-towered” is the preferred label.

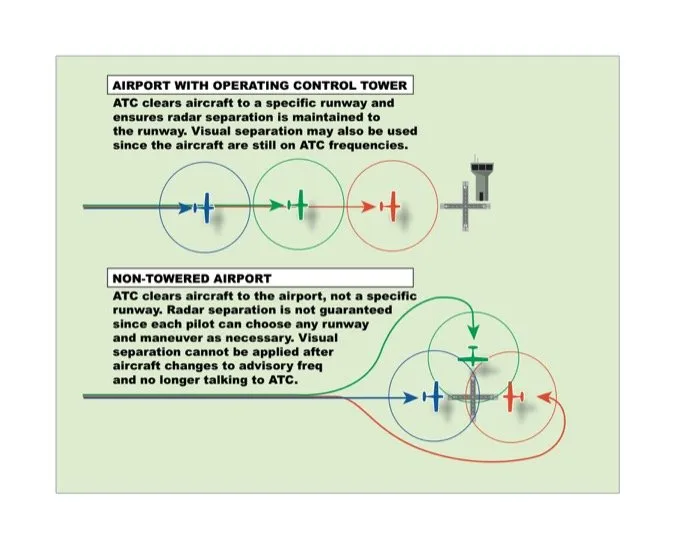

With a towered airport, controllers specify runways for landing and departure. They’ll list them on an ATIS and notify the overlying TRACON which runways are active. The radar controllers will then sequence arrivals to the advertised runways.

Let’s say I have a group of three IFR aircraft inbound to the fictional Plainview Airport. It’s daytime and the control tower is open. The airport has two runways: 9/27 and 18/36. Via vectors and speed adjustments, I’ve ensured the traffic is safely in trail and headed toward the advertised Runway 9. I’m required to maintain a minimum of three miles horizontally or 1000 feet vertically between each IFR aircraft (maybe more for wake turbulence).

Before I can clear an airplane for a visual approach, I have to ensure the pilot has either the landing runway, the airport, or preceding aircraft in sight. Obvious, right? If you’re landing on it or following it, ATC must ensure you can see it. For instance, if there are clouds in the way or the preceding aircraft gets lost in ground clutter or weather, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to safely navigate visually to the runway.

Since I’m sequencing him to a specified runway, my approach clearance must be for that runway. “Cleared visual approach, Runway Niner.” To the runway, not to the airport.

Chaos Theory

Now, let’s think about non-towered airports. Without an active tower there is no designated active runway. It’s up to each pilot—not ATC—to choose a particular piece of concrete.

Therefore, a non-towered visual approach clearance will only be to the airport, not a specific runway. This creates a whole host of uncertainties. Let’s cast aside all of my training, the regs, and better judgment, and live on the wild side for the moment. What kind of havoc can we cause?

Remember that three airplane sequence? Let’s say they’re aimed at the same airport and same Runway 9 as before. They’re all still perfectly spaced and safely in trail, at 2000 feet. However, it’s after hours now. The tower is closed. It’s a—you guessed it—non-towered operation.

Non-towered ops require the pilot to only report the airport in sight. Again, there’s no on-airport ATC to designate an active runway. It’s pilot’s choice. All three of my aircraft report the airport in sight. To each pilot, I say, “Cleared visual approach, Plainview Airport. Report cancellation of IFR in the air this frequency, or on the ground via [freq or phone number]. Change to advisory frequency approved.”

And here’s where things go off the rails. Up until this point, I had each aircraft radar-separated by over three miles or 1000 feet. When I say “change to advisory frequency”, that’s the same as saying, “radar service terminated.” We just leapt from radar separation to IFR non-radar separation standards. I’m not going to go into all of the radar/non-radar details. Just understand this: the three miles apart—radar separation—no longer counts.

Instead, I would have had to use altitude separation, which is legal non-radar separation. If the airplanes were locked at 2000, 3000, and 4000 feet, respectively, and stay there forever, I’d have been clean. However … all of the aircraft were at 2000 feet. Even if they were stacked, since they were cleared for visual approaches, they’d be descending to the airport’s altitude. Uh oh. I just had multiple operational errors.

Also, what is stopping aircraft number one from circling to Runway 27, number two hooking to Runway 36, and the third from landing Runway 9, all converging simultaneously on the airport? Nothing. They were all cleared to the airport only and can land on any runway they want. So, even if radar separation was allowed, there was no guarantee they’d keep that three-miles separation. Remember: all three aircraft are still IFR and must be afforded IFR separation.

To protect for those IFR separation requirements, ATC must only allow one IFR aircraft at a time in or out of a non-towered airport. We sterilize the airspace so they can safely maneuver as necessary and land on the runway of their choosing. Until we get the pilot’s IFR cancellation in the air or on the ground, or—if it’s been a while since the target dropped off the scope—call someone on the airport to visually verify the aircraft is safe on the deck, no IFR traffic can be allowed within its vicinity. This protects for unplanned IFR go-arounds as well.

No See ‘Ems

But what about pilot-applied visual separation? You know, the ol’ “see and avoid” that allows IFR aircraft to pass closer than three miles/1000 feet if one spots the other and either the pilot or controller says “maintain visual separation”? If you see the other guy, you won’t hit him, right? Sounds like common sense.

Let’s imagine aircraft number two had number one in sight, and the third had number two in sight. If the control tower was open, that would be easy. “Follow the [preceding aircraft]. Cleared visual approach, Runway Niner.”

Again, there’s a big requirement dividing towered and non-towered ops. Per FAA Order 7110.65 section 7-2-1 (a) (2): Pilot-applied Visual Separation: “Maintain communication with at least one of the aircraft involved and ensure there is an ability to communicate with the other aircraft.” These are part of our requirements for providing increased services and separation to IFR aircraft. If something unexpected happens, we need to be able to reach you.

If the control tower is open, the approach controller will eventually say, “Contact Tower.” The pilot will switch frequencies, and still be talking to a controller while he’s following the other airplane. Even if the pilot loses sight of the other aircraft, or never had him in sight at all, Tower can still visually separate the two airplanes. They can call traffic or make adjustments to the flight path or speed to provide additional separation if needed. To make those calls, though, tower-applied visual separation naturally requires the controller to be in direct contact with at least one of the aircraft involved. That’s in 7-2-1 as well.

However, if you’re inbound to a non-towered airport and ATC tells you, “Change to advisory frequency approved,” you’re gone from all ATC frequencies. You’re on your own. We have no way of reaching out to you. ATC facilities don’t often have UNICOM frequencies for their airports readily available. Since we cannot communicate with you, we can’t legally allow pilot-applied visual separation. Therefore, no, “Follow the [aircraft]. Cleared visual approach, Plainview Airport.”

Cancellation Received

These rules seem cumbersome at times. There will be moments—if you haven’t experienced them already—where you’ll be inbound to a non-towered airport and ATC will tell you something along the lines of, “Expect a delay for previous IFR arrival (or departure).” There’s nothing we can do about it. We can’t let you get too near the airport until the previous guy cancels his IFR clearance. These types of restrictions apply for departures as well, by the way. You may have to wait on the ground for an arrival or previous departure. It’s “one in or one out”. That’s an “or,” not an “and.”

What can you do about it? Cancel IFR as soon as it’s practical. Think about it: all of these regulations we’ve discussed only apply to IFR aircraft. When you cancel IFR, those stringent separation requirements go away. You can just proceed VFR to the airport. ATC can still provide flight following and traffic advisories until we terminate your radar service. In the meantime, though, we won’t need to keep you away from the airport, since the airspace sterilization is only IFR to IFR.

Often times, if you’re number one in a sequence of IFR traffic to the non-towered airport, ATC may give you a nudge, after giving you the, “Report cancellation of IFR…” spiel. I might say, “A prompt cancellation of IFR is appreciated. Multiple IFR aircraft inbound behind you.” That’s my not-too-subtle hint to you: if you can legally and safely cancel, please do so ASAP, because there’s a line of other IFR traffic waiting on you.

I do want to stress that if it’s neither legal nor safe for you to cancel, do not feel pressured to cancel IFR prematurely. Your safety is the highest priority here. All we’re asking is that, if you’re in a good position to help ATC and your fellow pilots out, it’s definitely appreciated. If the weather, your comfort level, or other factors don’t allow for cancellation, by all means you should keep that IFR clearance all the way to the deck. However, once you’re safely down, please don’t delay calling us to cancel. It’s that old golden rule: treat others as you wish to be treated.

There are so many benefits to getting “in the system” and flying IFR. The increased protection and priority afforded by ATC to IFR flights vastly outweigh the cost of a delay vector or two. When flying into non-towered fields, any resulting inconveniences are just that: minor inconveniences in the service of safety and order.

Missed Approach

Remember the IFR Baron at the start of this article, looking for a visual approach to a non-towered airport? Well, the King Air he was following cancelled IFR. I’ve cleared the Baron for the visual to the airport. After I give him the frequency or phone number for calling in his IFR cancellation, I change him to advisory frequency.

The pilot checks in on the airport’s UNICOM and announces his position and intentions. As he’s coming up on short final, though, a coyote wanders onto the runway and decides that warm piece of asphalt is a nice place for a nap. Facing the prospect of smacking forty pounds of Wile E. with his expensive airplane, Mr. Baron naturally executes a go-around.

So, we have two questions here: Is the Baron still IFR? What should he do now? First, yes, he is still considered IFR. He never reported cancellation and is still afforded full IFR services.

The second question is covered under section “e” of AIM 5-4-23, Visual Approach: “A visual approach is not an IAP (Instrument Approach Procedure) and therefore has no missed approach segment. At uncontrolled airports, aircraft are expected to remain clear of clouds and complete a landing as soon as possible. If a landing cannot be accomplished, the aircraft is expected to remain clear of clouds and contact ATC as soon as possible for further clearance. Separation from other IFR aircraft will be maintained under these circumstances.”

So, what should the Baron pilot’s course of action be? Well, since a visual isn’t an instrument approach procedure, there’s no defined missed approach procedures. Nowhere does it say, “Climb to this altitude, turn this way, fly to this fix, hold as published here, etc.”

Instead, he must play it by ear. Weather permitting, he can just go around and try another landing on the airport. Perhaps his go-around scared the coyote away and the runway is now clear. It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve seen a pilot do a low approach to shoo something furry, scaly, or feathery off the runway. If that won’t work, maybe try a different available runway if the winds cooperate.

Some situations, however, might make a landing impossible. Maybe he’s not getting three greens on his landing gear, and wants to divert to a larger airport with a more robust crash-response crew in case he has to land gear-up. Maybe a preceding aircraft had an accident and shut down the only usable runway. Perhaps the weather’s rapidly changing for the worse. Maybe a nearby fire’s reducing visibility significantly. There are any number of possible complications.

Under those circumstances, follow the AIM: “remain clear of clouds, and contact ATC as soon as possible.” Tell us what’s going on, and we’ll issue an appropriate clearance and instructions. These situations are why ATC strictly controls the flow of IFR airplanes in and out of non-towered airports. As the AIM says, “Separation from other IFR aircraft will be maintained under these circumstances.” We don’t have eyes on the ground, control over runway selection, or choice in what maneuvers a plane must make to land at a non-towered field. Therefore, we must protect for the unpredictable.

What’s one of Tarrance Kramer’s favorite pieces of phraseology to use while working traffic? “IFR cancellation received.” It’s usually accompanied by a sigh of relief.

I agree whole-heartedly with Terrance, and I teach the same to my IFR/IPC students. When you request a visual approach, the controller tells you to report the airport in sight. When you do that, a conversation ensues including the clearance, advising of how to cancel IFR, change to advisory frequency, etc. 95% of the time the pilot then cancels IFR, which requires additional response from the controller – likely taking about 20 seconds of valuable frequency time. Save everyone the time and simply cancel IFR at your earliest opportunity, assuming safety allows it. If there is any valid reason to maintain the IFR clearance to landing, by all means maintain it. But again, 95% of the time….

Love these real-world articles, always learning or re-learning something!

I wish there were less unnecessary ambiguity in the system when it comes to some implied expectations, e.g. when someone practices a low approach to a missed I think a clearer way to tell the student what to expect could be something like “Radar services suspended” instead of “terminated”, and why not always assume a straight-in unless the controller specifically says “fly the procedure turn”, or “cleared to descend” in some situations where one is cleared to a waypoint at a lower altitude than the current altitude.

The main advantage of keeping the IFR active through landing is SAR. When I call to cancel, they know I’ve landed safely.

With a VFR flight plan activated, SAR will be triggered unless I call (or text) to close the flight plan. Affirmative confirmation that I’ve landed safely. Cancelling IFR in the air leaves me exposed from the point of cancellation through the end of the flight.