Circadian rhythm is the daily alteration in a person’s behavior and physiology controlled by an internal biological clock in the brain. Body temperature, melatonin levels, cognitive performance, alertness levels, and sleep patterns are all subject to our circadian rhythm. A circadian challenge refers to the difficulty of operating in opposition to an individual’s normal circadian rhythms or internal biological clock. This occurs, for example, when the internal clock and the sleep/wake cycle don’t match the local time—like pulling an “all-nighter.”

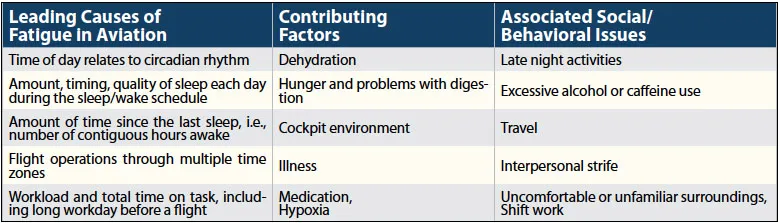

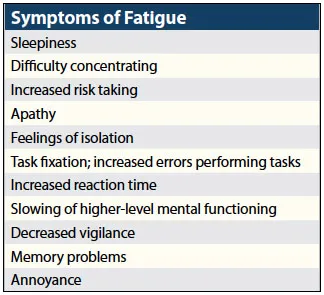

Fatigue refers to a physiological state in which there is a decreased capacity to perform cognitive tasks and increased variability in performance as a function of time on task. Fatigue is associated with tiredness, weakness, lack of energy, lethargy, depression, lack of motivation, and sleepiness. Accident statistics, reports from pilots, and operational flight studies show that fatigue is an evident concern within all aviation operations. (Advisory Circular No. 120-100, “Basics of Aviation Fatigue”)

A Fatigue Accident

A Cessna 182 RG crashed at night in marginal VFR conditions while maneuvering. A CFI and a student were on board. The CFI did not have a sleep disorder or take any medication to help her sleep. She liked to get about nine hours of sleep but typically averaged seven to eight hours.

On the evening before the accident, the CFI retired at about 8:00 p.m. local time to arise at 12:45 a.m. the next morning. She made a flight from Alabama to Florida between 2:27 a.m. and 6:45 a.m. The CFI then napped in the crew lounge at the FBO during the day, sleeping somewhere between two and four hours. Her student attended a meeting all day in Orlando before joining the CFI for their return flight.

The accident flight originated at the Orlando Executive Airport at 7:48 p.m. EDT. The aircraft was operating VFR and did not receive any ATC services after departure. A witness who lived in the vicinity of the crash site heard an airplane fly over at about 9:30 p.m. with high power. A short time later, he heard an impact and called the 911 to report the accident. There were no eyewitnesses, and the wreckage was located by a fire department at 10:37 p.m.. The CFI and the student pilot were fatally injured.

AIRMET Sierra was in effect for the area during the time of the accident. It indicated ceilings below 1000 feet AGL, visibility below three miles, with mist and fog. The NTSB speculated that loss of control was precipitated by spatial disorientation. They concluded that both the CFI and the student’s sleep patterns revealed both were susceptible to the effects of fatigue based on their sleep lengths during the 24 hours before the accident and their time awake before the accident.

Circadian Physiology

Pilots who feel best in the morning are referred to as “larks,” and those most energized in the evening are “owls.” After about 7 p.m., the circadian rhythm of performance begins to decline. If a person stays awake throughout the night, they will experience a strong early morning low in performance referred to as the Window of Circadian Low (WOCL). Occurring between 2 and 6 a.m., this is a period of low alertness and performance and elevated operational risk. It is also the optimal time to obtain restorative sleep.

There is a secondary dip in alertness in the early afternoon—the secondary WOCL, which is a period of increased drowsiness and performance risk lasting for several hours. The secondary WOCL is a relatively good time to get a brief nap if additional sleep is needed.

Fatigue and Its Causes

There are three types of fatigue: transient, cumulative, and circadian. Transient fatigue is acute fatigue brought on by extreme sleep restriction or extended hours awake during one to two days. Cumulative fatigue is brought on by repeated mild sleep restriction or extended hours awake across a series of days, and circadian fatigue refers to the reduced performance during nighttime hours, particularly during an individual WOCL.

A variety of medical conditions can influence the quality and duration of sleep. These include sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, certain medications, depression, stress, insomnia, and chronic pain. With these conditions, pilots should work carefully with their AME to ensure these conditions are adequately diagnosed and treated.

Fatigue can also develop from a variety of common events. A long day of mental stimulation such as studying for an examination or processing data for a report can be as fatiguing as manual labor. Fatigue also leads to a decrease in a pilot’s ability to carry out tasks, particularly those that require manual dexterity, concentration, and higher-order intellectual processing (Higher Order Thinking Skills, HOTS).

Work-Induced Fatigue

General-aviation pilots are usually not exposed to the same occupational stresses as commercial pilots, such as extended duty days, circadian disruptions from night flying, time zone changes, or scheduling changes. Nevertheless, GA pilots will still develop fatigue from a variety of other causes. Given the single-pilot operation of most GA flying and its associated relatively higher workload, GA pilots are just as much at risk to be involved in an accident—and perhaps even more— than a commercial flight crew.

In research studies, fatigued individuals consistently under-report how tired they were as measured by physiologic parameters. A tired individual truly does not realize the extent of their actual impairment. No degree of experience, motivation, medication, coffee, or willpower can overcome fatigue.

When I was a medical resident in training, we worked 12-hour shifts in our emergency room. We would begin on a Monday morning and work from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. for six consecutive days.

On the seventh day, we would not work during daylight hours but would report for work at 7:00 p.m. We would then work until 7:00 a.m. the next morning. Again, we did this for six days, got one day off, and then returned to the day shift. This alternating schedule continued for a calendar month, and by the end of the month, even those of us younger than 30 years were exhausted from the constant change from day to night and back to day shifts. Research shows that medical errors increased due to continual schedule changes.

During flight, fatigue may manifest itself through missing headings, altitude assignments, radio calls, performing routine tasks inaccurately, or forgetting them altogether. It can result in falling asleep for brief periods. Additional manifestations of fatigue include slow reaction times to changing situations, a failure to notice an impending traffic conflict, loss of situational awareness, or forgetfulness.

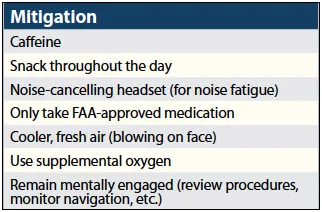

Countering Fatigue

Employ the I’M SAFE checklist before each flight. The Aerospace Medical Education Division of FAA recommends the following to avoid fatigue:

• Be mindful of medications’ side effects, including over the counter drugs that can cause drowsiness or impaired alertness.

• Consult a physician to diagnose and treat medical conditions that cause sleep problems • Create a comfortable sleep environment at home

• When traveling get into the habit of sleeping eight hours per night.

• Nap during the day, but no more than 30 minutes. Long naps produce sleep inertia—counterproductive.

• Retire at the same time each night. Get plenty of rest and minimize stress before a flight. Otherwise, rethink the flight and postpone it accordingly.

• Sleep is the only way to reverse sleepiness. Naps are beneficial for restoring both performance and alertness levels, especially during long periods of wakefulness. Even short naps of a half-hour can have beneficial effects.

Wilson, D. “Why am I so tired? – Fatigue on the flight deck,” in Human Factors: Enhancing Pilot Performance.

Fatigue in Aviation brochure at https://preview.tinyurl.com/fatigue9

AOPA Air Safety Brief “Fighting Fatigue.” https://tinyurl.com/fatigue10

[Got rid of Hsv in 2 weeks],,.