Sitting in seat 34F of a 737 MAX-9, I’m leafing through the dog-eared inflight magazine. It makes a big fuss about the airline’s offerings. Wi-Fi onboard, A/C power, luxurious first-class (in which I am not seated, alas).

What isn’t advertised? Unexpected aerial thrill rides. Who would’ve guessed violent maneuvers weren’t big sales movers for the general public?

However, some pilots out there place themselves in spots where their unexpected presence can turn someone else’s flight into a Six Flags rollercoaster. While technically operating within the bounds of regulations, they push the edges of common sense, breaking up established traffic flows and leaving air traffic controllers like me trying to predict their next move.

Telepathy Isn’t a Thing

Anyone who passed the private pilot written exam must be familiar with airspace classifications, and each classification’s communication and entry requirements. You must be able to point to a particular drawing on a sectional chart—a solid magenta circle, a dashed blue circle, or a weird combination of blue polygons—and tell your instructor what it is.

The equally important question is, Why do airspace classifications exist? Class B, C, and D—the ones that matter in this context—provide a controlled environment for those airport’s towers to protect and sequence their traffic.

Those bubbles are compromises. They only extend so far, and the patterns for these airports often exceed their protective shell. Where I work, we have a combination of Class C and Class D airports. Our busiest Class C only extends to the typical ten-mile radius, but our finals may extend to 15-25 miles during high-volume days.

Into this mix come unidentified VFR aircraft. Most aren’t a factor, remaining clear of the fray. However, some will skirt right along the protected airspace’s edge, not talking to ATC. Sure, they’re meeting their clear-of-airspace requirements. Unfortunately, they often find themselves wandering into a storm of IFR arrivals or departures.

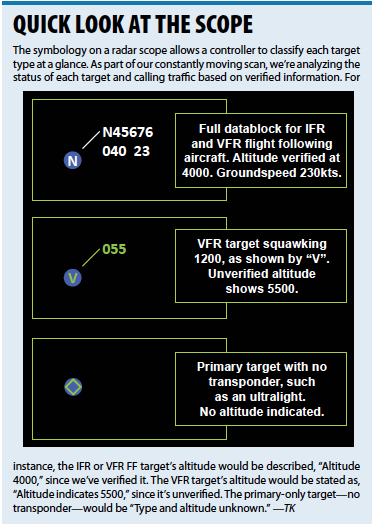

My job as a controller is to separate and sequence aircraft. Doing so requires verifiable information. Now, these VFR aircraft may very well have the latest and greatest traffic information system onboard and have every airplane around them in sight. Perhaps they’ve got their altimeter set to the local area. Maybe they’re intending to fly a straight line and stay at their current altitude for a while, and not do any crazy maneuvers.

However, if a pilot’s not talking to me, I have no idea of his intentions, if he sees the traffic around him, or even if the altitude I’m showing for him is correct. I can vector around the target and issue traffic, but I don’t really know what they’re doing. It’s high stakes guessing.

I’d also like to state something clearly: Controllers recognize that those VFRs have a right to fly there. However, it’s like someone driving at 45 mph on the 70 mph freeway. They are legal to do so, as long as it’s above the minimum speed limit and stick to the right lane. However, all other vehicles—also observing the traffic laws—must swerve around them or slam on their brakes to fall in behind them. This interruption to the regular traffic flow can become a dangerous distraction.

Invasive Action

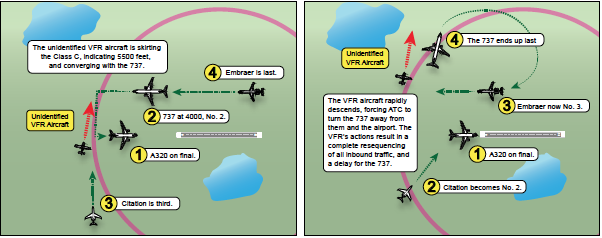

Case in point: One afternoon, I was working four jet arrivals into our airport, one of which was a 737 on my left downwind, level at 4000 feet. I already had an A320 on a straight-in final. The 737 was going to be number two. Jet number three was on an extended right base. Number four was ten miles in trail of the 737, also at 4000.

I’d noticed a slow northbound VFR target indicating 5500 feet on a converging course with the 737. My radar tools showed that they’d miss laterally by only 0.2 miles. I called the traffic to the 737. “Traffic, ten o’clock, five miles, northbound, converging course. Altitude indicates 5500.” The crew said they were looking for it.

The traffic had seemed to be maintaining a steady course and altitude. Suddenly, I noticed the target’s altitude change—5400… 5300…. Our downwinds run at 4000 for noise abatement purposes. Of course, we are authorized to violate that protocol for safety … which is exactly what I did, telling the 737, “Descend and maintain 3000.”

The target’s descent rate was increasing: 4800 … 4500 … 4200… I called traffic again, but the crew couldn’t spot him. “Descend and maintain 2000.” That was my minimum vectoring altitude; I could go no lower. The 737 was dropping through 2900. The traffic continued to descend: 3800 … 3500… He didn’t seem to be leveling off any time soon.

Altitude separation wasn’t going to happen. My only option was a hard turn. In another situation, further away from the airport, I would’ve gone left, to pass behind the slow traffic. I couldn’t do that here, with the A320 already on final at nearly the same altitude as the 737.

Instead, I racked the 737 hard right to a 030 heading. It would initially parallel, and then veer away from the northbound traffic. Of course, I was betting that the VFR aircraft didn’t make any more unpredictable moves. At least this was in the final descent phase, where all the passengers were required to be buckled in. Hopefully the flight attendants were already seated or had steady footing.

Of course, this threw my sequence completely out of order. The number three jet on base took the 737’s original spot, becoming number two as I tightened up his turn to final. The fourth jet, originally following the 737, became number three. I then vectored the 737 around to fall in behind. He’d fallen to last in line through no fault of his own.

Had this VFR aircraft just called me, knowing that he’d be passing very close to a major airport, I could have verified his altitude, then told him, “Maintain 5500 until advised for traffic. Traffic, two o’clock, five miles, westbound, 4000. Boeing 737.” We would’ve avoided all the conflicts, maneuvers, and distraction that ensued.

And You Are?

Often the targets getting in the way seem to be low-and-slow single-engine props, typical Skyhawks and Cherokees out for some flightseeing or training. They just happen to do that a bit too close to congested airspace. However, as a controller, one quickly learns that a VFR target on your scope can be just about anything. I’ve seen a little “V” on my scope turn out to be an F/A-18, a Grumman Wildcat WWII warbird, or a C-130.

Also, while ATC shouldn’t make assumptions about targets, some pilots do seem to make assumptions about airport traffic volume. Just because an airport is a Class C, and not a lofty Class B, doesn’t mean they can charge right on in and be number one every time. We mid-level facilities can push some traffic too.

A friend of mine was working our East radar sector, handling a 10-plane arrival push into our main airport. I was on West, handling departures, taking them up to 10,000 and handing them off to Center for further climb. I’d noticed there was a fast VFR target doing laps at 10,500. I’d already had to issue traffic calls and avoidance vectors to my climbers.

Then a call came. “Approach, Learjet 123AB. We’re at 10,500, 15 miles northeast of your airport. We’re looking to shoot the RNAV 27.” Ah, there’s the guy. I issued him a squawk and handled some other traffic. He was already descending into my friend’s sector. I was going to radar identify him and hand him off, so my friend could give him vectors for sequence.

The Lear’s target acquired … aimed directly at the closest initial approach fix for the RNAV 27. “Learjet 123AB, radar contact, altitude indicates—” I stopped. His altitude read XXX. He was in such a rapid descent the radar couldn’t keep up with him. “Say altitude?” I said. “We’re out of 4500 for 2000,” he said, “direct to [IAF].”

My friend already had multiple aircraft sequenced for that IAF at 2000. The Lear was plummeting directly into them. “LearJet 123AB, stop your descent immediately. Maintain VFR at or above 3000 for traffic.” Meanwhile, my friend yelled across the room, “Hey, who is this 3AB guy?” I yelled back, “I’m stopping him at 3000.” My friend started calling the Lear traffic to his other arrivals. He’d been a hair away from tearing them off their approaches.

I had to get this Lear out of the way. “N123AB, turn left heading 360, vector for sequence.” This northerly turn, away from the IAF, set him up behind my friend’s arrivals. “Uh, Approach,” the Lear said, “we said we’re requesting the RNAV 27.” I said he could expect it. “Well, we’d like a turn towards [IAF].” It was the tone of someone used to getting his way all the time.

“Sir,” I said, ”you’re currently number eleven. And you were descending on top of three other aircraft that were already setup for that approach.” A moment passed, then he spoke, the attitude gone. “Oh, sorry, I had no idea you guys got that busy here.” From there on, he was a pleasure to work, and he got his approach.

Let’s be clear: the IAF was outside the Class C. This LearJet did nothing illegal dropping into it. Where he went wrong was assuming he was the only airplane in the sky. If he’d waited until he’d been identified, instead of divebombing at the IAF into a swarm of other airplanes, it would’ve been a whole lot cleaner.

(Don’t) Hit the Silk

In the preceding examples, I could see an indicated altitude for each VFR target, even if it was unverified. Why? They had transponders.

Are there transponder-less flying machines out there? Sure—Part 103 aircraft, which include ultralights, trikes, and paramotors. No transponder means no altitude readout. Our radars might see one as a primary-only target, meaning it just appears as a dot on our radar scope. However, our radars have a moving target filter, designed to weed out targets moving below a certain speed. An ultralight in a headwind might not even register. So, they might be invisible to us.

Mix these slow, small, hard-to-spot machines with high speed jet traffic and things can get, um, interesting. “But wait,” you say. “How high can these things really fly?” One YouTuber—Chucky Wright—released a video in Sep. 2021 where he flew his paramotor up to 17,500 feet without oxygen. He was reportedly just outside a Class B.

In the video, he’s floating around 500 feet shy of the flight levels, complaining about it being hard to breathe (no comment…) and pointing out the jets passing nearby. Again, he’s perfectly legal to do this. The Mode C veil around Class B airports doesn’t apply to him. He’s below the IFR-clearance-required Class A airspace. Two million-plus views later, as of this writing, how many imitators do you think he’ll get?

In the field, I’ve had pilots suddenly maneuver to avoid no-transponder paramotors and other ultralights. With inconsistent radar detection, possibly due to their slow speed, I was forced to give wide vectors around the reported area to other traffic. “Delta 1522, use caution. Ultralight reported at two o’clock, eight miles, altitude reported 3000. I don’t have him on radar.” The invisible threat is moving too, albeit slowly. In five or ten minutes, who knows where or how high he could be.

Again, they’re operating per Part 103 regulations. They have a right to fly there, even if it’s low level on final for a major airport. It’s just not fun for those either working the airspace, or flying through it.

ATC gets that if a pilot is flying VFR, they often just want to be left to their own devices. However, if you find yourself flying VFR near potentially congested airspace, keep in mind the impact you could unwittingly be having on other IFR and VFR traffic. The big sky isn’t that big, and legal doesn’t always mean safe.

You are given airspace to manage your approaches. I suggest that’s what you do and keep your approaches within that airspace and quit complaining about what you are not authorized to control. Maybe you have to stack them when busy, maybe a few short vectors. Just keep them within the airspace and everyone will be safe.