Launching a flight with passengers, into iffy weather, with just enough fuel, can be stressful. And that’s when everything goes just right. If it doesn’t, what starts as one small issue to handle can become a series of problems. Before you know it, you’ve got yourself a monstrous single-pilot workload. And just to make matters worse, you wished you’d taken along your FAR/AIM…

So Far So Good

The day starts in Mansfield, Ohio by stuffing your Piper Arrow to its max gross weight. The plan is to stop for fuel at Queen City Municipal in Allentown, Pennsylvania on the way to Massachusetts. You load three other people, bags and as much fuel as weight permits—25 gallons. Meticulous flight planning shows 1.7 hours to get to KXLL, burning 9.2 gph. This leaves one hour of reserve, slightly buffering the legal minimum 45-minutes of 91.167(a)(3). And, you’ve diligently followed 91.103 as far as knowing “all available information” for the flight, including weather, runways and some backup airports should you need to stop en route.

You needn’t file an alternate airport per exceptions in 91.167, and its 1-2-3 rule. The terminal forecast for Allentown’s Class C airport a few miles away says it’ll be scattered clouds at 1800 feet with rain and 5 miles visibility at your ETA. The only thing to really keep an eye on is scattered thunderstorms that could move towards Allentown.

The Deluge Hits

You level off at 11,000 feet in the middle of a high overcast; the airports on the way are reporting marginal VFR with light rain. The “radar” feed on your tablet shows a bunch of little green and yellow blotches ahead north and south of your route, suggesting you could get through or around, if necessary. For the next half hour, though, you fixate on the precip spreading out more and more and wonder how much fuel you have to zigzag around all that.

Smack in the middle of Pennsylvania, ATC advises you of “moderate to heavy precipitation” at your 12 o’clock, 10 miles ahead. Your little display, which could be several minutes old, now shows a blocky chunk of red amid lots of yellow. “Roger,” you reply, and then consider what to do. Steer around, left or right? The best place seems to be south of course. You request and get 20 degrees to the right. The worsening bumps tell you that wasn’t enough.

Then rain starts pelting the Piper with so much clatter that you’re forced to turn up the radios. Turbulence starts to cause 100-foot changes in altitude and although you’ve got bigger problems, you worry about busting your assigned altitude, violating 91.179 (a). You work on keeping wings level and get another 15-degree heading change. This is not a good time to try remembering how a turbulence report works in Chapter 7, Section 1 of the AIM, so you work on keeping wings level and remain silent.

Holding On

It would sure be nice to get in the clear so you could see and hear what’s going on. What about 13,000 — would that cause issues as far as 91.179, IFR cruising altitudes? You also recall there’s some reg about when supplemental oxygen is required, something you don’t have. (That’s 91.211(a)(1), when above 12,500 feet for more than 30 minutes.)

Now one of your passengers is getting airsick, likely from the altitude and turbulence. You request for 9000 and hear nothing but static in your ears and rain outside. You can make out Center giving weather deviations to a couple of aircraft, but it’s impossible to tell where they are. You try again, and thought someone answered but you’re not sure. Now what? Do you revert to the lost communications procedures in 91.185? Do you know 91.185? How do you get down to an alternate you never filed?

So, increasingly nervous about fuel and an airsick passenger, you squawk 7600 and decide to parallel your original course because you don’t want to go back into worse weather. Suddenly, the turbulence tapers off, it gets quieter and you can hear the radio again. After smoothing things over with Center, you’re told to expect weather delays into Allentown and get a reroute direct to East Texas. By now you’re beaten, battered and your ears are ringing, so hearing “East Texas” baffles you for a few seconds as you ask for the identifier. Are they sending you to another state, and do they know you don’t have the fuel to get there?

Fuel! Suddenly, you realize that all this time, you had forgotten to switch tanks. There’s probably a gallon in the left tank and (hopefully) at least seven in the right. You make the switch, power down, and lean out as much as you dare. You punch in ETX on the navigator. Phew. It’s 10 minutes ahead, northwest of KXLL. You think you’re already hitting that 45 minutes of fuel reserves; do you need to mention anything about minimum fuel? It’s all laid out in AIM 5-5-15, but you can’t recall if this advisory gives you any priority. (It does not.)

How To Get In?

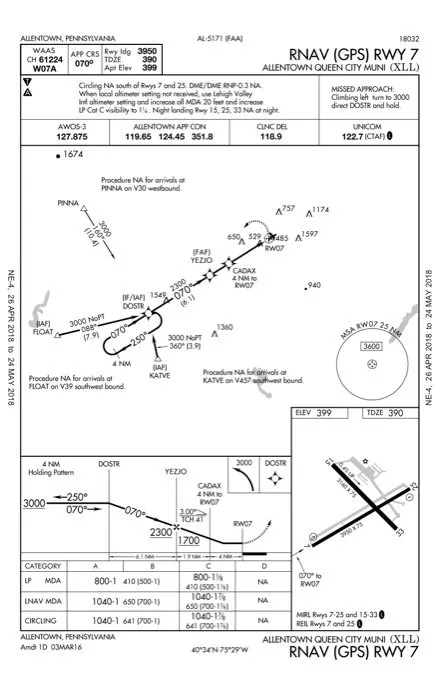

Allentown’s bad weather decided to move in early, so now you’re up against two miles of visibility in rain and storms already encroaching on the Class C airspace to the north. Upon reaching ETX, you get a reprieve through a clearance for the RNAV 7 KXLL starting at DOSTR and a descent to 3000 feet. You’ve been heads-down on the descent looking at the IAP. It has one of those darn holds-in-lieu-of-a-procedure turn, and it appears that from your course to DOSTR, you must fly it.

After this grueling hour, you’re exhausted and it’s difficult to fly and monitor the regs at the same time. AIM 5-4-11, if you had it handy, would tell you what to do. How do you get a shortcut, and did anyone mention you’re low on fuel? You then realize you’ll have to fly the teardrop from your southerly course to DOSTR and the 070-degree final approach course. Since it’s the only option to get down sooner rather than later, you go for it.

Ceilings aren’t an issue here as the clouds really are at the forecast 1800 feet scattered at KXLL, and while visibility is still marginal at three miles now, you have no problems seeing the runway at the FAF. You even remember to put the gear down, configure flaps, and manage to land in a normal fashion, considering what you’ve put yourself and your passengers through. It sure won’t be fun watching the helpful line tech put 20 gallons of fuel back into your Arrow, but you’ve already decided to wait out the weather now so you’ll use a lot less of it on the next leg.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. Her penchant for bookmarking pages of her digital FAR-AIM and reciting subparagraphs has her fellow pilots imposing strict screen-time limits.