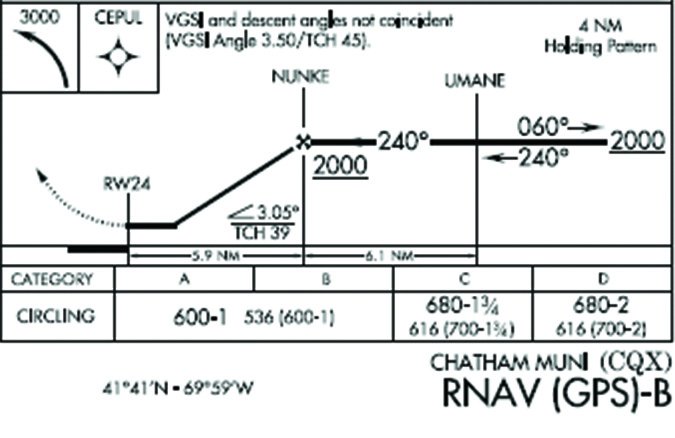

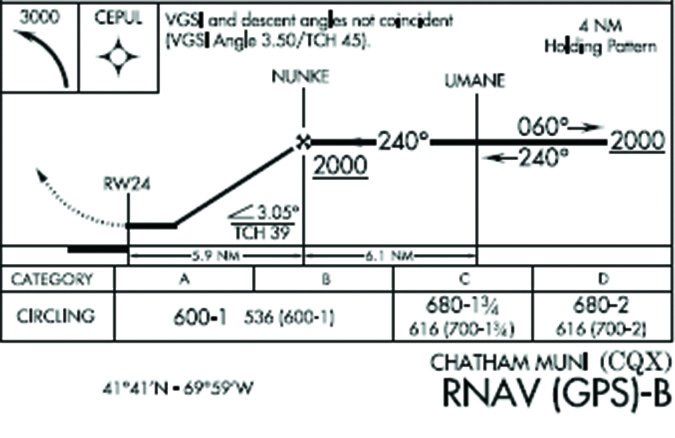

Recently, a reader asked about a puzzling approach at Chatham, MA (KCQX). The RNAV (GPS)-B is perfectly aligned with Runway 24 and the descent angle is a routine 3.05 degrees, yet it has only circling minimums. Approaches most often just have circling minimums if the alignment to the runway exceeds 30 degrees (for most procedure types) or the descent angle is greater than 3.77 degrees (for Category C and below). So, what’s up at Chatham?

This procedure has only circling minimums because of the runway markings, of all things. The runway has basic, visual markings; straight-in minimums require at least non-precision instrument runway markings. This little detail isn’t found on the chart or in the Airport/Facility Directory, but can be found in online sources, such as Airnav.com, which are based on FAA airport survey data.

Other than runway dimensions, fuel availability and the distance to the nearest restaurant, pilots don’t think much about airport infrastructure. However, as shown by Chatham, perhaps a bit more attention to the infrastructure is in order.

See a Runway Down There?

Who cares if the approach at Chatham only has circling minimums? It’s an instrument procedure aligned with the runway with a normal descent angle. This procedure can only be flown to non-precision LNAV minimums because of the circling-only requirement. Considering the frequency of fog in that part of Massachusetts, with better markings, the airport’s utility might improve with lower LP, LNAV/VNAV or LPV minimums.

Visual runway markings are generally just the runway number and centerline stripes. Adding threshold marks—the stripes immediately after the beginning of the usable runway—makes it a non-precision instrument runway. Precision instrument markings also require an aiming point, touchdown zone markings and runway edge markings. Runway markings were thoroughly discussed in Jordan Millers fine article, “How Far Can You See” in the August 2015 issue.

These standards are found in the airport design manual, Advisory Circular AC 150/5300-13A. Since it’s an Advisory Circular, it’s technically non-regulatory, which gives the FAA the flexibility to occasionally bend some of the rules when there’s a need. As a result, you’ll occasionally find some instrument approach procedures into some unusual airports.

In the past, runway marking requirements were often relaxed to enable straight-in minimums to runways with only basic markings, so they do exist. The rules are also bent for approaches to turf and water runways, obviously with no markings. Outside Alaska, however, unpaved runways are seldom considered and only in special cases.

For an unpaved runway to support an approach, the runway must be clearly identifiable. The threshold and edges must be clearly defined, such as with tires, cones, or grading. Procedures to unpaved (unmarked) runways are published as circling-only procedures, and night operations are prohibited without approved lighting.

How’s the Weather?

Weather reporting infrastructure for an airport can also impact instrument procedures. While Part 91 operations can shoot an approach at an airport with no weather reporting, that’s not true of commercial operations. They need to know the weather before they can start the approach, thus requiring on-field reporting.

Also, a weather reporting system is required for an instrument procedure to be a legal alternate—a common reason some procedures are marked “Alternate NA.” Similarly, when the weather reporting becomes unavailable (rogue snowplow, for instance), the airport usually can’t be used for alternate planning. This is why there’s typically a note to this effect for each airport in the non-standard alternate minimums section.

Regardless of weather reporting to support instrument procedures, at least one altimeter setting source is required. Lacking a weather station, we use the remote altimeter setting source (RASS).

If there’s no local altimeter source, the approach will be based upon one from a nearby (or not so) airport and there will be a “Use Big City Int’l altimeter setting” note. If a remote altimeter setting source is used, a penalty (the RASS adjustment) of increased minimums is applied to the intermediate and final segments. This adjustment accommodates the potential for pressure differences between the remote source and the approach airport.

Depending on the type and dissemination capability of the primary altimeter source, a secondary altimeter source may be required. If so, there will be a note like, “When local altimeter setting not received, use Big City Intl altimeter setting and increase all MDA 80 feet.” Note that the RASS adjustment is already in the published crossing/step-down altitudes. If you’re using the secondary altimeter source, you need only adjust the MDA.

Occasionally you find a note on approach charts like, “…except for operators with approved weather reporting service.” Commercial operations require local weather, so they might have their own private certified sources if the airport doesn’t provide it full time.

Uh…My Needle Isn’t Moving

We usually assume that navigation facilities are in working order, which is why they’re monitored—internally, remotely, or both. How facilities on an instrument procedures are monitored impacts whether that procedure can be considered for alternate planning.

A procedure will be notated as “Alternate NA” when the facility providing final course guidance, identifying the non-precision final approach fix, missed approach guidance, or a facility required for procedure entry is not remotely monitored. Remotely monitored facilities alert the monitoring facility whenever there is a problem. However, sometimes the monitoring facility is a control tower or FBO that isn’t always operating, so the non-standard alternate minimums section is annotated, for instance, “NA when control tower closed.”

Occasionally you’ll see a NOTAM that a particular facility is temporarily unmonitored. That means the remote monitoring link is out of service, but the facility is still internally monitored. If there is a problem, the facility will shut itself down, but ATC only knows about it when a pilot complains that their needle isn’t moving.

Until 2013, RNAV (GPS) approaches were not authorized for alternate planning, so some “Alternate NA” notations linger. In addition, RNAV (GPS) approaches that only have LPV minimums (usually with LNAV minimums on a different chart), are not authorized for alternate planning because only LNAV or circling minimums may be considered during alternate planning.

A NOTAM for That?

Lighting is another element of airport infrastructure that impacts instrument procedures. Longer approach lighting systems permit lower visibility minimums, consequently with a penalty if they aren’t working. In addition, depending upon the obstacle environment off the approach end of the runway, an operable visual glideslope indicator may be required for the approach to be usable at night.

Modifying the infrastructure at an airport is usually an expensive and time-consuming process, so we don’t recommend lining up outside your local airport manager’s door with a wish list. However, we should recognize how many aspects of instrument procedures are tied to the physical aspects of the airports served.

Whenever you read a NOTAM about an equipment outage at an airport, such as the ASOS, an unmonitored navaid or an inoperative approach light system, consider the implications of that failure. Chances are it will have some impact on the approach procedures at the airport. If the implication of that failure isn’t on the approach chart, it will be published as an FDC NOTAM, so make sure to pay particular attention to those as well.