(This is the first of a four-part series of articles in which contributing editor Fred Simonds will fully explore common, oft-fatal mistakes that we pilots make. This first article merely relates a number of ultimately harmless incidents that will serve as illustrations on which we’ll build in subsequent articles. As I read Fred’s manuscript, I was struck at how truly common some of these incidents really are. As a pilot flying en route high above, I’ve heard some incidents like these unfold. As a pilot down low, I’m forced to admit that at least parts of some of these incidents sound a bit too familiar. In each of these incidents reviewed here, fate (the hunter, remember?) allowed the pilots to complete their flights with no more than injury to their pride or perhaps a serious discussion with the appropriate ATC facility. It’s easy, however, to imagine a darker outcome. You know the old expression, “Live and learn.” Well, another suitable title for this series could be “Learn and Live,” but I wanted to stick with the attention-grabbing, sensational title author Simonds used because, well, it’s simply true. —Editor)

A Visual in IMC

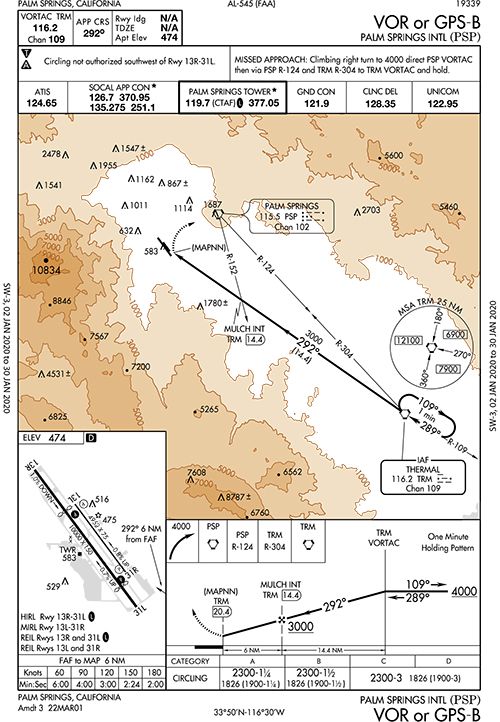

Unusually, Palm Springs International (KPSP) in southern California was socked in with rain and low clouds. And it was night. An aircraft on the VOR-B reported they barely saw the field at circling mins, 2300 feet MSL.

Shortly afterward, the tower controller was handed another aircraft, thinking he also was on the VOR-B. It later developed that the airplane’s radar tag mistakenly said VOR-B, but SOCAL TRACON (SCT) verified that he was cleared for the visual approach. The aircraft called “field in sight” but was low, triggering a Low Altitude Alert.

Scanning for the plane with binoculars, Tower relayed the Low Altitude alert and verified that the pilot still had the field in sight. The aircraft was at 600 feet, four miles out, abeam a 1780-foot obstacle. At three-plus miles, the aircraft began climbing and said he needed to go around. He realized that what he thought was a runway, wasn’t.

The controller was sure that the pilot became disoriented and mistook a road for the runway—a not uncommon mistake. Tower issued missed approach instructions and handed him back to SCT. Bolstering the controller’s belief, the pilot instead returned to the tower frequency, said he had the field “now,” and landed safely. The controller asked him to call after parking.

The pilot claimed to have broken out at 4000 feet and had the field in sight all the way down. Given the field conditions, the recent PIREP, and the Tower’s inability to spot him visually with binoculars, this was a tough sell but would have legitimized his request for a visual approach. If the weather was that good, why did the pilot try to land on something he thought was the runway three miles short of the real thing?

The controller saved his life, but the pilot could have done more to safeguard his flight. He didn’t realize he’d lost situational awareness until the controller spoke up. This was the time for an instrument approach, not a visual. He failed to notice that his “runway” lacked visual features like the PAPI, runway lights, and beacon. He could have asked that the lights be turned up, or stayed higher to help find the airport. The pilot took a shortcut with an illegal visual approach. Had he flown the procedure, he might have avoided his loss of situational awareness and the illusory runway that nearly cost him his life.

Do as You’re Told!

A GA aircraft was under IFR and level at 9000 feet when the controller received a Minimum Instrument Altitude (MIA) alert. He instructed the aircraft to climb to 10,000 feet to clear the MIA and immediately called the airplane again to inform him that he needed to vector the aircraft to avoid military airspace. The pilot started to question him, but the controller pressed on, telling the pilot he needed a vector or would have to cancel IFR and enter a military training complex at his own risk. Plus, the aircraft was not climbing. The controller repeated his climb and heading instructions.

The pilot started to climb but too late. He’d already entered the MIA box because he failed to follow instructions. He was also confused, and his delayed responses precipitated a loss of separation. The controller summed it up concisely: “Pilots need to take action when given a clearance.” In a similar incident, an already busy

controller responded to an aircraft request for a GPS 12 approach, so he cleared them to an IAF for the approach. Unexpectedly the aircraft turned south into a higher 5600-foot MVA. The controller issued a Low Altitude Alert and instructions to climb to 5600 feet, but the aircraft did not comply. He then issued a heading to the north and a climb, but again the aircraft did not respond or comply.

Some IFR pilots fail to internalize the fact that IFR is seriously scripted. This clueless pilot flew an unapproved heading and altitude and stumbled into an MVA. The AIM says, “When ATC issues a clearance or instruction, pilots are expected to execute its provisions upon receipt.” He could have hit an obstruction or another aircraft.

Mooney Mission Mindset

The Mooney pilot departed S50 in Auburn, WA, to practice approaches in IMC. He filed a Round-Robin IFR flight plan. The S50 weather was marginal VFR due to stratocumulus clouds, with better than six miles’ visibility, ceilings 1500-2000 AGL and tops reported at 3000-5000 feet MSL.

In the run-up area, the pilot reached Seattle Clearance Delivery, but they were too busy to issue his clearance. Alternate frequencies did not work. He departed VFR and remained in the pattern to try again. ATC advised that if he flew south into another sector, his clearance might be deliverable.

This didn’t work either. The ceiling had risen enough to let him climb to MVA but he lost sight of his escape route and nearby airports. He realized that if conditions worsened, he could be trapped without a clearance. That’s precisely what happened. He became disoriented and entered IMC but eventually landed safely.

On later reflection, he realized that deciding to take off into the pattern, traveling south, and climbing through a “hole” were all hazardous. Once he decided to return to S50, he considered declaring an emergency to get a clearance rather than trying to navigate down through the clouds and to the airport. In retrospect, this would have been wise.

Said the pilot, “I should have dealt with the clearance on the ground, not in the air. When talking to SEA Clearance, I should have been more direct to see if they could help get my clearance, and if not, then don’t depart.” Mission mindset in full control, he assertively took off expecting an airborne clearance that might never come, leaving himself few if any ways out.

Keep your perspective and remember every flight is optional.

Ice is for Drinks, not Airplanes

Flying his Mooney Ovation, this pilot encountered icing conditions even though his aircraft was not legal to operate in ice and he knew beforehand of an icing AIRMET. He planned to stay below the cloud layer until clear of clouds, then climb in VMC to an altitude too cold for icing.

The plan was upended when the clouds proved lower and more widespread than expected from his weather briefing, picking up trace ice at around 10,000 feet. He informed ATC and, with their help, decided to climb to 16,000 to get out of icing conditions. He immediately began to climb and was soon in temperatures well below freezing and out of icing conditions.

He later realized he’d misinterpreted the satellite weather depiction as showing the only places where there were clouds or clouds with moisture significant enough to produce icing. He learned that this is not the case.

Knowing that he didn’t know, he faulted himself for not making a no-go decision based on the icing AIRMET. As he said, “That would have been the prudent thing to do.”

TAA Trouble

The 3500-hour ATP was en route to Tracy, MN, in a Cirrus SR-22. The weather report was clear at KTKC. Expecting a visual approach, the pilot discovered

that the weather had deteriorated to 400 feet broken. The LNAV MDA for RNAV 29 was 445 feet AGL. The pilot elected to try, hoping to emerge below the broken layer.

Reinforcing his decision was the Garmin Perspective avionics suite aboard with LNAV+V vertical guidance for many LNAV approaches and synthetic vision. He followed the vertical navigation down to MDA and continued past the VDP 1.3 miles from the threshold. Too high to land on the short 3000-foot runway, he went missed.

Flying to the IAF for another attempt, he noticed a large hole in the clouds that would legally allow him to descend into Class G airspace, then proceed to his destination. However, he was uneasy because towers or terrain might lurk below. But he had flown many straight-in approaches to Runway 29 at Tracy and knew there were no obstacles on the approach path. He chose to try again.

As before, he followed the VNAV down the final approach. Reaching MDA, he still did not see the runway. He elected to descend a little further. At about 150 feet below MDA or 290 feet AGL, he saw the runway at 12 o’clock, on glide path, exactly like any other precision approach. He landed.

Not many pilots deliberately consider flying below minimums and that includes this pilot. However, get-thereitis, along with a formidable avionics package that provided vertical advisory guidance and synthetic vision that displays the runway ahead (“there is no more IMC”), tempted the pilot to turn a nonprecision approach into a homemade precision approach.

In his words, “…this is an excellent lesson for anyone flying TAA aircraft. They certainly can give the feeling of invulnerability in several areas, including instrument approaches, fuel planning, and thunderstorm avoidance with XM weather. Invulnerability is a classic human factors pitfall, and a powerful one at that.”

TAAs were expected to decrease the accident rate, but they did not. One speculation is that TAAs allow pilots to nibble at the edge of safety. This narrative

shows how easy that is to do.

A Flight to Die for

The Cessna 172 departed under VFR from Custer County Airport in Custer, SD, and called Denver Center for his IFR clearance to Billings, MT. The Center issued a squawk code, then noticed the pilot had filed for 8000 feet where the area MIA is 9300 feet. He asked the pilot if he could climb to 10,000 feet as a final altitude due to the MIA. The pilot responded negatively and that he was IMC climbing through 7500 feet. ATC instructed him to maintain VFR and reminded him that he did not have an IFR clearance.

The Cessna descended to 7300 feet and said he was trying to stay VFR. When asked if he could see the ground, he said yes, and there was a cloud layer above at 7600 feet.

Again, ATC asked the pilot if he could maintain terrain and obstruction clearance and climb to 9300 feet. Once again, he replied no. He said he would try to stay VFR until ATC could give him a clearance. Instead, ATC suggested he return to his departure airport. The pilot added that he thought he could stay VFR.

As the pilot descended to 7100 feet, ATC suggested a westerly heading out

of the Black Hills into lower terrain if he could maintain VFR. He said he would and crossed the boundary into the controller’s 9000-foot MIA airspace at 7300 feet, above terrain and obstacles in that immediate area. ATC then issued him an IFR clearance with a climb to the MIA at 9000 feet, and he complied with

the clearance.

This pilot’s problem was inadequate flight planning. KCUT’s field elevation is 5620 feet. He filed for 8000, although the local OROCA is 9500 feet. An airway northwest of CUT has a telling MOCA at 9200 feet and MEA of 13,000. No wonder he got into trouble so fast. He could have easily avoided busting VFR minimums because KCUT has 24-hour clearance delivery service. Had he used the tools at hand and picked up his clearance while still on the ground, he would have avoided risking his life.

Illusions, disobeying ATC, completion bias, unexpected icing, false invulnerability, and shoddy flight planning are a few ways pilots tempt fate. You may think, “I’m too smart. Couldn’t happen to me.” These pilots likely thought the same thing.

I’m familiar with a MOCA and MEA. What does the acronym MIA stand for? (Other than Missing in Action) 😆

Minimum IFR Altitude (MIA). Minimum altitudes for IFR

operations are prescribed in 14 CFR Part 91. These MIAs are

published on IFR charts and prescribed in 14 CFR Part 95

for airways and routes, and in 14 CFR Part 97 for standard

instrument approach procedures

Are the MIA’s really on the IFR charts, such as the Enroute Low Altitude charts? Where is that information and how is it depicted?

Minimum IFR Altitudes:

https://aviationglossary.com/mia/

WOWWW. These are “really” BORING mishaps. Can’t you come up with anything better than these??

The more exciting ones are published in the Obits.

Twit

Dear William,

Hi, I’m Fred, the the author of this article.

Among other things, IFR attempts to inform readers of close calls others have experienced in an effort to prevent recurrences. It does not publish articles for dramatic effect or amusement, but we try to keep it interesting, as with the On The Air segment on the last page of the magazine, sort of like dessert after a good meal.

I don’t like writing about fatalities. Many pilots have a morbid fascination with accidents, especially fatal ones. I have never understood this mentality. Too much of that stuff can begin to play with your head, in that it begins to undermine pilot confidence. This is unrealistic and unfortunate because by far most flights are completed safely and without drama. You don’t hear about those, but they far exceed the fatalities.

I selected these occurrences very carefully from 50 ASRS reports for their learning value, relevance and uniqueness, and I hope you gained from it.

Thanks for your comment, and for subscribing to IFR. There is no magazine to match it anywhere.

Kind regards,

Fred S.

Free Enewsletter????? On your website, there is an offer to “Sign up today for IFR’s FREE weekly eletter, BRIEFINGS!” I signed up for this about a month ago, and when I click on “Continue reading” in the email I receive, I’m directed to your website with the instructions “To continue reading this article or issue you must be a paid subscriber”. What a joke!

You’re reading the offer incorrectly. 🙂

The enewsletter is free with a paid subscription to the paper version of IFR magazine. You have to sign up for it separately in order to receive it. Get a paid subscription. It’s worth every penny.

Why do you send emails highlighting an interesting article and then waste our time by making it a subscriber-only view when we go to your website?

A more professional approach would be to find value in the linked article that would lead me to subscribe. Instead, you punish your prospective subscribers with a bait and switch.

R E A D

These are great, well written articles and I appreciate them as an instrument pilot. Please ignore the internet trolls.

Hi Chris,

I’m Fred, the author of this article. I’m delighted that you appreciate them. We work hard to keep the articles great and well-written. We set the bar very high, which is why I love writing for IFR. It’s packed with information and there is no fluff. If you want the real skinny on IFR, this is the magazine for you — and it’s the only one of its kind.

Thanks for your kind words and for subscribing!

Fly safe,

Fred

Keep up the great work!

But I’m not sure about the tone of the vinette ‘Do as You’re Told!’. It’s tone is a bit ATC authoritative and the pilot has final say in operation of the aircraft. Granted the instruction were legitimate and needful and the pilot needed to comply to keep his flight safe. Yes the pilot may have been clueless or rather disorientated and behind the aircraft. The tone of ‘Do as you’re told’ turns pilots into unthinking robots, which they are not and that attitude can lead to issues. I can’t count the times I’ve told ATC ‘unable’ .

Hi James,

I’m Fred, author of this article. Under IFR we are expected to comply with ATC instructions. As you wrote, their instructions were necessary and needful.

“Do As You’re Told” was written for pilots whom I expect know all about 91.3 and 91.123. The latter says in part, “When an ATC clearance has been obtained, no pilot in command may deviate from that clearance unless an amended clearance is obtained, an emergency exists, or the deviation is in response to a traffic alert and collision avoidance system resolution advisory.”

It continues to say that “Except in an emergency, no person may operate an aircraft contrary to an ATC instruction in an area in which air traffic control is exercised.”

I also reiterated what the AIM says in this regard: “When ATC issues a clearance or instruction, pilots are expected to execute its provisions upon receipt.”

It was in the context of the above regs that the section title was chosen. All these rules provide for exceptions either explicitly or on the understanding that 91.3 trumps all.

I FULLY concur that pilots should NEVER be unthinking robots. We are expected to be critical thinkers and have our heads fully in the game. Hey, that’s where the fun is! In a subsequent article, I wrote that pilots should never let ATC fly their airplane, and a pilot who did came close to packing it in.

You make an excellent point and it deserves repetition. We’re on the same page!

James, thanks for writing and for subscribing to IFR. Your support is much appreciated.

Fly safe,

Fred

Good stuff for a soon to be IFR pilot!!!

To the folks complaining about not being able to view the article because they’re not subscribers: subscribe. This publication is invaluable and needs your support to keep going.

Great info…..keep em coming!

Let’s keep learning, from each other and our collective mishaps and triumphs.

Former subscriber. I’m a fan of Aviation Consumer, AvWeb, Light Plane Maintenance, and AvWeb, but agree with those who think that IFR magazine has become too “authoritarian.” Despite the title and subtitles, nobody died in these incidents. Instead, the author faults the pilots.

In the first incident, a more perceptive author would have noticed that there was simply an error in terminology. Had the controller and/or pilot used the term “Contact Approach” instead of “Visual Approach” (the difference is having the “runway environment” instead of the airport–1 mile and clear of clouds)–there wouldn’t even have been an “incident.”

In the second incident, the pilot is faulted for “delaying his climb”. The controller has obviously not “worked” a Cessna 172 at high altitude–the climb rate is anemic. He COULD have given the pilot a vector for the climb, but didn’t.

In the Mooney “potential icing” incident–part of the problem is with ATC–multiple attempts to wangle a pre-filed clearance–this was NOT a “pop-up.” As it turned out, he picked up only a “trace of ice”–though the writer describes it as an “icing incident.” Pure hyperbole. Ice is where you find it–there is no predicting it other than a pilot report. In Minnesota, “chance of icing” occurs half the year. It is NOT reasonable for the controller to “head into another sector, where a clearance might be deliverable.”

In the last example–the pilot was fully compliant with ATC. The writer faults the pilot for “inadequate flight planning”–then cites the 13,000′ MEA. The writer obviously has not flown a Cessna 172, with an inability to climb that high unless light (not to mention lack of oxygen).

As others have pointed out, the writer defends ATC and “the system”–even though (unlike the titles) nobody died in these incidents. It’s a classic case of “are you up there because I’m down here” vs. “are you down here because I’m up there?” More succinctly–“Whose chair is bolted to the aircraft, and whose chair is bolted to concrete?” IFR magazine MISSED the point–and badly. Bring in Paul Bertorelli from the rest of Belvoir Publications for some real-world experience and practical commentary.

Ah, Light Plane Maintenance has been dead for years. Authoritative, not authoritarian is more accurate.

Hi Jim,

I’m Fred, author of this article. I read your comments with care, and I’d like to respond.

We try never to be authoritarian, but as Bill Ross said, authoritative. We are very sensitive to this because we’re not here to pontificate what pilots should, let alone must, do. We know there is often more than one right way to fly an airplane.

No, nobody died in these incidents, as our editor noted, but they came close. Of the 50 ASRS incidents I reviewed, I selected only six and omitted ATC errors because they primarily concerned the internal workings of ATC and were not helpful to pilots.

In the first incident, it was up to the pilot to request a suitable approach. Niggling about a visual versus a contact approach, which the pilot must request, misses the point. The weather demanded the full-up VOR-B as the first aircraft flew successfully. As I wrote, the pilot took a shortcut with an illegal visual approach.

In the second incident, the pilot pushed back at the controller and failed to obey a previously issued climb instruction from 9000 to 10,000 feet. If the pilot had difficulty complying, he should have said so. The service ceiling of a 172 is between 13-15,000 feet, and even then, it’s still climbing 100 fpm; 10,000 should have been no problem. The controller repeated his climb and heading instructions, so he did issue a vector for the climb, but the pilot failed twice to follow instructions and wound up in the MIA box. Simple as that.

Jim, you mixed two Mooney incidents into one paragraph, so let me parse them out. In the first instance, the Mooney attempted to obtain a filed clearance without success. There was no mention of a pop-up or ice. As for the “reasonableness” of heading into another sector, the controller tried to help, which sounded perfectly reasonable to me.

In the second incident, the Mooney Ovation pilot knew beforehand of an icing AIRMET into which he could not legally fly. He had to assume ice was present. Icing AIRMETs are predictive and not to be ignored, although PIREPs are indeed better. His attempt to mitigate it failed because the clouds were lower and broader than briefed.

Icing, no matter how slight, demands immediate exit because it can quickly get worse. There is some and none, and some is too much. I don’t see any hyperbole here, but I do see a responsible pilot who took immediate corrective action.

In the last example, the pilot filed an IFR flight plan for 8000 feet. Since MIAs are uncharted, he had no way to know directly of the 9300-foot MIA. ATC could not offer him an IFR clearance unless he could climb to 10,000 as a final altitude. For whatever reason, the pilot responded negatively. He informed ATC that he was IMC, climbing through 7500 feet, admitting that he was illegal on tape. ATC told him to maintain VFR and reminded him that he did not have an IFR clearance.

The pilot advised there was a cloud deck at 7600 feet. Unable or unwilling to accept 9300 and at 7100 feet, ATC suggested a westerly heading toward lower terrain. The pilot complied. He entered a 9000-foot MIA at 7300 feet, but no matter since he was VFR. ATC then issued him an IFR clearance at 9000, which the pilot inexplicably accepted. For just 300 feet higher, he could have complied with the first MIA.

His flight planning errors are readily apparent. The OROCA above KCUT is 9500 feet, just 3880 feet above field elevation. An airway northwest of KCUT has a MOCA of 9200 feet and a 13,000-foot MEA, which the pilot did *not* fly as you suggested. Had he looked harder, he would have realized he needed to file for higher. Glancing at a Sectional would have given him the situational awareness he required, showing the Black Hills to the east.

He could have avoided the whole problem by contacting Clearance Delivery on the ground. You claim “the pilot was fully compliant with ATC.” This is not true. He failed to comply with ATC’s altitude instructions multiple times and busted IMC to boot.

As for your final remarks, I wrote it as it happened. Wise pilots learn from the mistakes of others, which was my sole intention here.