Some of the best remote scenery is in northernmost Utah, well away from the hubbub of Salt Lake City. Dozens of mountain peaks, ranges, national forests and year-round resorts all make the mid-size city of Logan a nice destination. Logan-Cache airport offers everything you need to fly in and enjoy the area. While travel choices abound once you’re there, flying back out is a different matter.

The Scenic Route Down

The ILS 17 is spectacular as you overfly the surrounding mountains and descend into the valley. Airport elevation is 4457 feet—amidst much higher sector altitudes. It’s a 16-mile final after your 10,000-foot transition from the Malad City VOR. While that’s a longer final than usual, the only thing close to being inconvenient was a long taxi to the south ramp, but you landed long and shaved a mile off the drive.

Time to Get Out (Up)

You’ve enjoyed your brief visit, so you vow to come back, probably in the summer. Your pre-trip review uncovered that there’s just one IFR route to get you back over the terrain to the northwest. But you didn’t count on IMC hanging over Logan at about 3000 feet, blocking the scenery. You conclude that you can get out now, but you decide to run the calculations for a return in summer temperatures, otherwise using today’s conditions.

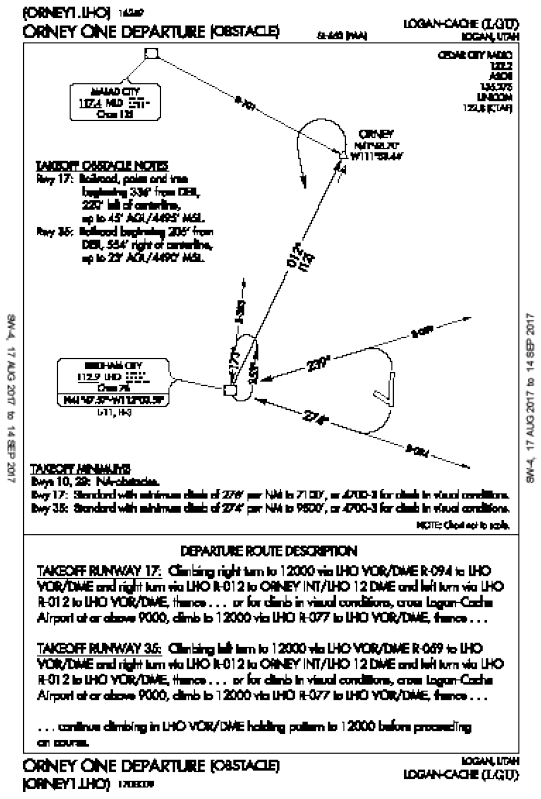

Winds are 10 knots from almost straight north, so you’re committed to Runway 35. There’s one departure procedure, the graphical ODP, ORNEY ONE.

The Runway 35 takeoff minimums are “Standard with minimum climb of 274′ per NM to 9500′, or 4700-3 for climb in visual conditions.” Your first question is if can you climb 274 feet per mile at gross weight with you, two passengers, and baggage loaded into your Arrow?

Your EFB might have a calculator to figure your climb rate for 274 feet per mile, but that’s just the starting point. You’ll be consulting the POH to determine climb performance, getting the real departure-time weather, and then deciding if you can safely depart Logan and fly the DP to 12,000 feet. You figure this now by determining the minimum conditions required to see if it’s realistic in summer.

Got PA and DA?

Start with a standard Climb/Descent table or calculator, which converts feet per NM to feet per minute.

First convert the Arrow’s 100 MPH to 87 knots. Allow for the headwind and round to 80 knots ground speed. The required 274 feet per NM works out to about 365 fpm for the Arrow.

From 4457 feet MSL at the airport, you’ll have a climb of about 5000 feet to reach the 9500 feet MSL in the DP. Temperature and pressure come into play here, since performance charts are based on pressure altitude adjusted for temperature (density altitude). Again, use a density altitude table (some POHs include one) or a calculator. Let’s assume a standard day of 29.92, with a summer temperature of 32 degrees C, dew point is 4 degrees, and the pressure altitude right at 4457 feet. One calculator on the web says the DA is about 7500 feet.

Making It Work

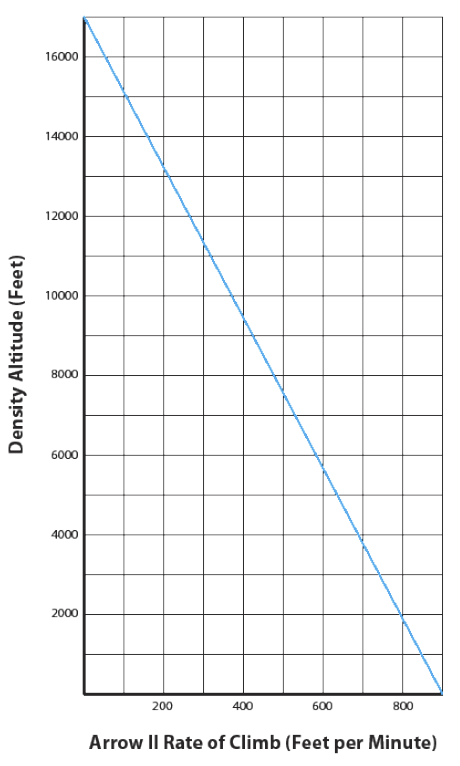

Now on to the Arrow performance chart. Using round numbers and maximum gross weight, density altitude of 7500 feet on the ground means an initial climb rate of about 500 FPM.

Since we’re climbing about 5000 feet (to 9500 MSL) on the departure, starting at a DA of about 7500 feet, add that 5000 feet to the climb performance chart and, assuming a standard lapse rate, see that at 12,500 feet we’ll climb about 240 fpm.

This leaves you wondering how tedious the climbout will be. To get more specific, figure out how high you could maintain that 365 fpm needed for the departure procedure.

Again using the Climb Performance chart, we get 365 fpm at about 10,000 feet DA. With the ground at 7500 feet DA, we can only meet the required climb performance until about 2500 feet AGL or about 7000 MSL, short of the DP’s 9500.

Another catch is that this assumes the same conditions apply from when you first took off. Of course, everything varies with altitude, including groundspeeds. What needs to change so you can safely fly this for real?

Options include getting the aircraft lighter by leaving behind fuel or stuff (or people, but they usually don’t appreciate being left behind). Choice two is to depart at a different time, like early in the morning when the temperatures will be a lot cooler. Best bet? Exercise both options. Stop into Logan and ship the luggage home, and plan an early-morning takeoff.

IMC Or VMC?

There’s another option to use on top of the aircraft considerations, and that’s departing under IFR with clear skies. Visual conditions would be nice for a few reasons. If there’s a mechanical or performance issue, you’ve got the airport and relatively clear space beneath if you must abort the procedure. Plus we all get to enjoy another look at that scenic valley. And the departure procedure provides more leeway when you’re visual.

Check again on using Runway 35, and you’ll see the DP calls for “standard with minimum climb of 274′ per NM to 9500 feet, or 4700-3 in visual conditions. If you have those conditions or better, you can fly over the airport “at or above 9000, climb to 12000 via LHO-R-077 to the VOR/DME, thence … continue climbing” in the VOR holding pattern to 12,000 feet before heading on course. So if you stay visual, you must be above 9000 feet while over the airport, then you can continue on up to 12,000 while heading west on the 077 radial back to the VOR. This route is shorter than the full DP, allowing you to go right to LHO to finish climbing to 12,000.

Whew. Now back to the full DP itself, just to make sure you have the whole picture. The chart clearly shows there’s some back-and-forth maneuvering while climbing all the while. It calls for the takeoff minimums applicable to 17 or 35, followed by the appropriate climbing turn to 12,000 to the LHO VOR/DME, then a right turn northeast to ORNEY intersection, then a left turn back to LHO, then you’re to “continue climbing in LHO VOR/DME holding pattern to 12000 before proceeding on course.” So whether visual or not, the idea here is to be high enough to leave the airport environment, then reach 12,000 feet before leaving the valley and heading over the mountains.

Knowing you have figured out what’s required from the ground up to make a tricky departure work will ensure you’ve covered all the pieces, particularly those that aren’t obvious, such as climb gradients and ever-higher density altitudes. Not sure if any particular piece will work? Start with what will, then go from there, so you can enjoy that wonderful mountain view rather than wishing it wasn’t there.