Much of general aviation activity in piston-powered airplanes is for recreation—the proverbial $100 hamburger ($1000?) on nice sunny weekends. Still, there are many general aviation pilots who fly—using the technical phrase—”for the furtherance of business.” We’re not talking banner tows, flight instruction, skydiving, or true commercial endeavors. “Furtherance of business” denotes those operations that are only “incidental to that business or employment.” (14 CFR 61.113)

A typical example is using your bird to travel to a business meeting. According to the 2016 annual general aviation survey conducted by the FAA, one in five piston-powered aircraft flights are for such a mission.

Let’s take a look at how the risks in these flights can differ markedly from the hamburger hop. We’ll also peek into the accident database to get a feel of the safety record for this chunk of GA. Finally, we’ll wrap up with lessons learned to benefit pilots undertaking such operations.

Risks

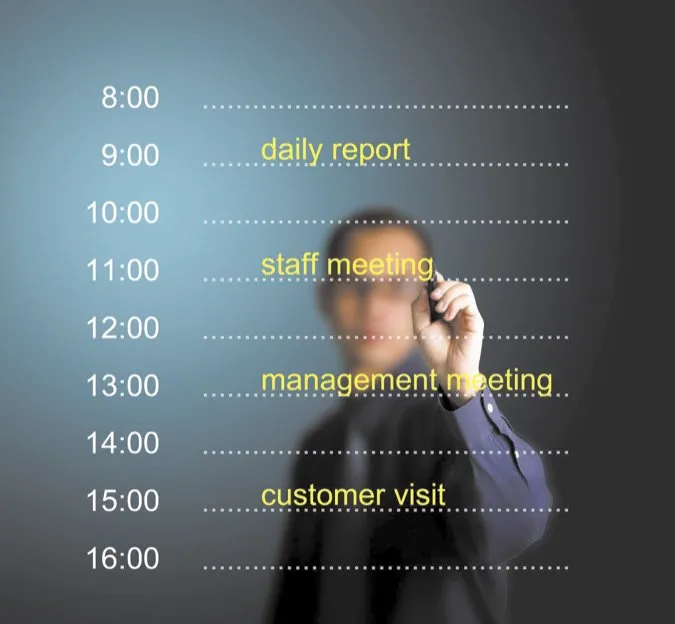

Not too surprising, a huge difference between recreational and business flights is schedule flexibility. You’re a successful business person and “free time” is not in your lexicon. The early meeting on Wednesday in Commers City means you need to arrive Tuesday night. But a Tuesday afternoon meeting at the office means your departure for Commers City can’t happen till that evening. You also have another meeting in the office first thing Thursday. You can see where this is going.

First, how often does Mother Nature comply with the best laid plans? A front bringing IMC or adverse weather is forecast for your route. “No problem,” you think. You’re instrument rated, have a gazillion hours and a heap of time-in type. Plus your money-oozing business allowed you to get all the new cockpit toys. Your panel rivals what the big guys have. What could possibly go wrong?

Business commitments that squeeze your Commers City meeting reduce (eliminate?) your options. Leaving the office early to beat the weather is out and likewise cooling your heels in Commers City will nix your meeting the next day.

Limited options and flight safety bear an inverse relationship. Many pilots have prematurely redeemed their life-insurance policies because of this. Don’t forget fatigue—with a tight schedule chances are this flight could encounter IMC, be at night, require an approach to minimums—all after a strenuous day at the office. Fatigue from the office or the flight depletes your peak performance reservoir. Yup, these are all risk factors for accident flights that have snared too many pilots flying for business.

Of course, human factors rear their head too—in a research study the FAA came up with the fancy term “goal seduction.” The implication, as the FAA found, is that the more one has to gain the more one will take on risk. We’ve known that for some time from air medical services which historically have a poor safety record (although recently it’s improved dramatically).

The Research

I admit it: I’m a propeller-head—an academic Ph.D. who researches flight safety. There’s little for me to do with the airlines as they’re so safe and so well studied already. Regrettably there’s ample research to do about GA pilots getting into trouble, since we do it so often. Perusal of the NTSB accident database for the last five years shows one fatal accident by domestic air carriers compared with 959 for general aviation. Yeah, sadly, there’s plenty to work with.

But, there is some good news for those of us whose flying is in furtherance of business. This accident rate has been halved between 1996 and 2015. That’s impressive. Maybe those whiz-bang toys help as much as we told our accountants in justification. Or perhaps the recent emphasis on scenario-based training has had a positive effect. Still, let’s put the gain in flight safety into perspective. Much as there is to brag about improvements in general aviation flight safety we’re still a long way off compared with the pros.

Then, the bad news is that even with a declining accident rate, the percentage of fatal accidents on business-related flights (33 percent) was much higher than the 15 percent cited for general aviation as a whole. These weren’t freshly minted general aviation pilots flying on business-related missions either. The pilots who got snared boasted an average of over 3000 hours total and 572 hours in type; and three-quarters of ’em held instrument ratings. Neither were these guys infrequent fliers who took the machine up for a monthly jaunt to dust off the cobwebs. Nope, these pilots were, on average, racking up 55 hours in the last 90 days. That’s serious GA flying.

So what went wrong? Not surprisingly, for nearly half of the fatal flights, the NTSB laid blame squarely on the pilot. The main culprits were poor control of the airplane under instruments, deficient stick and rudder skills, and lack of systems knowledge. In fact, 42 percent of fatal accidents in IMC were because of deficient instrument skills. If you think that doesn’t compute given the pilots’ experience and proficiency, we’ll dig deeper into that later.

The second common category was aviators who decided that regulations were only made to be broken. Some of these seem to think that minimums are only advisory in nature. Others chose to depart into instrument conditions without a flight plan or with a flight plan but without the requisite currency (and, presumably, proficiency). Scud-running was also popular deviant behavior—perhaps the errant pilot thought that their (supplemental and advisory only) terrain/obstacle warning system was a reasonable substitute for visibility.

One in five fatal accidents involved pilots deciding to practice unusual attitudes by penetrating a thunderstorm environment (and its offspring, windshear) and/or icing. Interestingly, a recent study found that only a minority of pilots on instrument flights heed the FAA-recommended distance (20 miles) for circumnavigating extreme thunderstorms (reflectivity of 50 dBZ or greater). Flaunting the regulations also came in the form of some pilots deliberately flying into known icing presumably to explore the limits of their aircrafts’ ability to carry ice. Regrettably, it’s obvious that homo sapiens are the weakest link in the accident chain. In fact, less than 10 percent of fatal accidents were chalked up to equipment failure.

NTSB investigations can sometimes overlook the possibility of fatigue as a factor. More than 80 percent of these accidents involving flights for furtherance of business were on a weekday and of these one third began after 16:00 local time. Chances are that quite a few of these pilots had a busy day and likely were not at their peak performance. What might have been a not-particularly difficult flight in IMC (or even VMC at night over poorly lit terrain or a body of water, like a certain pilot named Kennedy experienced) for a well-rested pilot could become challenging for the same person when fatigued.

These weren’t short hops either for a light aircraft—the average distance was 280 NM with the longest stretching to 890 NM. For a C182 chugging along at 140 knots, the flight time for the average trip would be about two hours. Add in a full day of work and stress and that starts nibbling at one’s performance.

Lessons Learned

What can we glean from these accident flights undertaken in pursuit of business activities?

Unfortunately, lack of proficiency on the gauges is nothing new. A 1983 NASA study querying instrument pilots found that a big concern back then was maintaining IFR proficiency. Unlikely that’s changed—as they say, the more things change the more they stay the same. Sure, we have a bunch of affordable aviation training devices (ATDs) at our behest. Are folks using these? Perhaps…

I suspect part of the problem here is that most of these devices are set up to simulate training aircraft such as Cessna 172s. Finding an ATD configured similar to your Bonanza or Mooney is unlikely—more unlikely if you’ve added all the newest toys to the panel. So, maintaining proficiency might require loading up your favorite flying buddy as a safety pilot to go shoot some practice approaches. Don’t be miserly—aim for more than the “six-in-six” in the FAA regulations.

Also, respect the insidious effects of fatigue. This topic is off the radar for many of us. After all, there are no duty limits and little training on the subject (in sharp contrast with the airline duty rules in Part 117). Those eight hours taken for the long, probably stressful, meeting should probably be added to the planned flight time and pre-flight planning. Why not use the duty limits of 8 hours with a mandatory rest period of 10 hours that the airlines use?

Do you have a long meeting at the other end? Consider opening up your day-after schedule to allow for a return flight following a good nights’ sleep. If your schedule doesn’t permit that, consider flying with another pilot (bribes by way of springing for hotel and meals can be effective incentives) or hiring a professional pilot. Then, there’s nothing wrong with an occasional commercial flight. Better yet, use commercial flights as a continuous Plan B.

Don’t assume that all of the whiz-bang toys that grace instrument panels today magically transform your light aircraft into a transport-category aircraft. Some pilots boast about their turbo-charged aircraft being able to “fly above the weather.” Uh, really? Sorry, you’re not going to climb over a thunderstorm towering up to 35,000-40,000 feet in your turbocharged Cirrus.

Similarly, a SiriusXM subscription or FIS-B will not give you what you need to penetrate lines of storms or even a single cell. To do that you need onboard weather radar. Also, few GA airports have terminal Doppler radar for advance warning of wind-shear. One pilot and his family in Texas found that out the hard way back in 2015. With a fairly mundane METAR advertising calm winds and thunderstorms 20 miles distant (presumably also shown on his SiriusXM subscription) the pilot launched. On departure, the plane was caught in wind-shear with a subsequent loss of control. There were no survivors.

A final word of caution: Complacency can breed over-confidence. As we saw, many of these pilots were well experienced. Frankly, Mother Nature doesn’t care about your logbook. Always respect the environment, even on a route you’ve uneventfully flown a gazillion times before.

The Concorde flight was an Air France charter taking passengers to New York to pick up a cruise to Manta, Ecuador. Flight 4590 was delayed and eventually assigned runway 26R for departure from Charles de Gaulle airport. However, because of a tail wind (090 at 8kts) the airplane was over-weight, not over the maximum allowable take-off weight, but because of an exceedance of the tire speed limit from the higher ground speed required to reach flight airspeed. This exceedance could have been addressed by requesting the reciprocal runway 08L but CVR recordings indicated not even a whisper of discussion on this point, (which the investigation board thought strange).

No, they were in a rush. The flight was late and the passengers needed to catch this cruise. Think of what might have happened if changing to 08L had been done. Would the tire have been ruptured by the metal strip? Unlikely. But even if so, there’s a chance it could have happened before decision speed allowing for a rejected takeoff. One can only wonder.

Douglas Boyd Ph.D. a research scientist (Professor University of Texas-retired) and active pilot, prefers the hamburger hop to flying for furtherance of business. He gets his academic jollies researching how general aviation pilots master the art of bending airplanes.