We all learned how to fly procedure turns when we got our instrument rating. We probably even had to fly a procedure turn or two on the practical test to qualify for the certificate. But since then it has been vectors to final nearly every time and our ability to fly a procedure turn correctly might have suffered in the interim. So let’s reawaken some old memories—or worse, create some new ones—by taking a detailed look at what it takes to fly a procedure turn the right way.

Know When

One of the most common points of confusion I see with students flying procedure turns is knowing when they are required and when they are not required. The first thing to realize is that procedure turns are never optional. In a given situation you either must fly the procedure turn or you may not fly the procedure turn. It’s not your choice to make.

Let’s begin by examining those situations where a procedure turn should not be flown. There are five of them: 1) if you are given radar vectors to final, 2) if a segment or area you are flying is labeled NoPT, 3) if there is no procedure turn depicted on the chart (can’t make up your own), 4) if you have been cleared for a “straight-in” approach, and 5) if you have been given a timed approach from a holding fix.

If any of these five situations applies to your approach, then you are not allowed to fly a procedure turn. If none of these is true then you must fly a procedure turn.

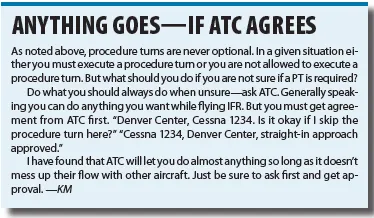

Of course, there’s an exception. Say you are on an approach where there is a procedure turn depicted, but for some reason (vectors, NoPT leg, etc.) you’re not supposed to fly it. But, suppose you’re high and fast and just simply behind everything and need the extra time in the procedure turn to get yourself oriented. Ask the controller for permission to fly the procedure turn and you’ll likely get it, although this might require going back out to a different IAF, depending on where you are relative to the procedure turn. (See the sidebar on page 11.)

Let’s examine each of the no-procedure-turn situations. Radar vectors are pretty obvious. The controller helps us get established on the approach so flying a procedure turn obviously would mess up the plan. You simply can’t fly a procedure turn if you are being given radar vectors to final.

But be sure that you are actually getting radar vectors. Generally speaking the controller will tell you that you are about to receive radar vectors before giving them to you. But simply being cleared direct to a fix on an approach is not vectors to final. You need to be given a magnetic heading to fly if you are receiving radar vectors.

The second instance where you cannot fly a procedure turn is if a segment you fly is labeled NoPT. Many approaches will require a procedure turn when coming from one direction and disallow a procedure turn when coming from another direction. Increasing numbers of GPS approaches have entire areas (rather than just a particular segment) that disallow a procedure turn.

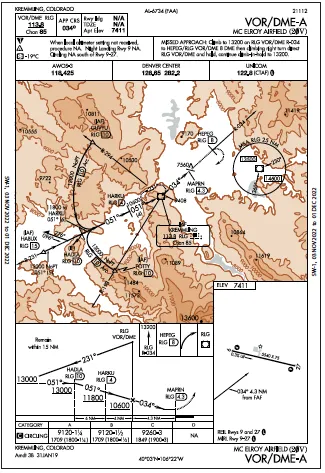

Take a look at the VOR/DME-A approach into 20V (Kremmling, Colorado) on the next page. If you begin the approach at HABUX or on either arc, you will be on a segment that is labeled NoPT. But if you intercept the segment between HARKU and the Kremmling VOR (RLG) then you have bypassed the NoPT segment and will need to go all the way to the VOR, do a 180 and then fly the PT.

Seems crazy doesn’t it. This is where a “straight in” approach comes in. A clearance for a straight-in approach demands that you do not fly the procedure turn. So if you had intercepted between HARKU and the VOR, then you could ask for a straight-in clearance.

Once given the straight-in clearance you are not allowed to fly a procedure turn. On a couple of occasions I have heard pilots who had been issued a straight-in clearance get chastised by ATC for attempting to execute a procedure turn. They were about to mess up a carefully orchestrated flow.

Timed approaches from a holding fix theoretically still exist but in the last 40 years I’ve never once heard one being used on the air. In the case of timed approaches, ATC will have several aircraft stacked up at a fix with each of the aircraft spaced 1000 feet above each other. As the bottom aircraft is cleared for the approach, each aircraft above is cleared 1000 feet lower and the process starts over.

The controller doesn’t want the bottom aircraft to take the time to execute a procedure turn and mess up the timing, so procedure turns are not allowed while this procedure is in effect. But as I said, timed approaches from a holding fix are as rare as hen’s teeth these days.

Know How

Once you determine that a procedure turn is required, how do you execute the turn? Procedure turns clearly have to begin at some point. But determining when to begin the procedure turn sometimes confuses pilots. The answer is simple.

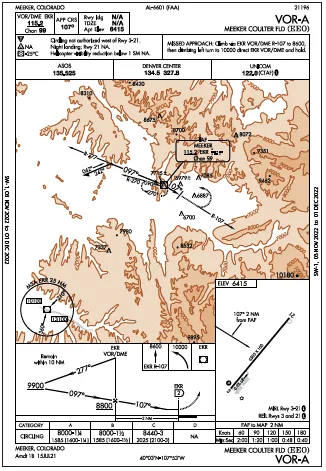

Take a look at the profile view. For example, the VOR-A approach at Meeker, Colorado (KEEO) begins at the Meeker VOR (EKR) and then continues out on the 277-degree radial. Note that this is the radial from the VOR and not merely a heading. While outbound, your altitude should be at or above 9900 feet. The inbound turn for most procedure turns must be completed within 10 NM of the start point (the EKR VOR in this case.) But be sure to consult the profile view to know how far out you’re allowed to go.

Many times I see pilots watch their GPS and as soon as it tells them to begin the course reversal, they begin the turn. This can be a problem. Most navigators will tell you to start the course reversal as soon as possible, and for many of us this can be too soon, before we’re stabilized.

The GPS is assuring that faster aircraft don’t get too far away. But in Category A and B aircraft, it pays to go out near the limit. This way, when you intercept the course inbound, you will have more time to get established and prepare for the rest of the approach. So don’t rush the turn. If you have GPS or DME, go out for about six miles before you begin the turn. That way when you do turn outbound you won’t exceed the 10 NM limit. If you don’t have GPS or DME, or as a backup, time for about four minutes outbound when at 90 knots ground speed. Try it in VMC to make sure it works.

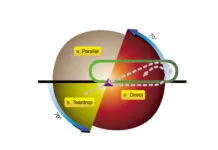

Once you decide that it is time to begin the turn, what heading should you take? Certainly what is printed on the chart is a reasonable way to go. But it is not legally required that you follow it. AIM 5-4-9.a.1. tells us that the type of turn and location of the turn is at the discretion of the pilot as long as the turn remains on the protected side of the procedure. I prefer to do what is printed on the chart, just so I won’t need to do any math to figure out my headings.

The 180 degree turn back to the track inbound is started after one minute. Generally it is best to make the turn away from the beginning of the procedure, again just to give yourself more time to become established inbound.

But remember you must stay within the specified distance of the beginning of the procedure. Once you turn back towards the inbound course, you will have about a minute or slightly more to become established. Use this time to reset your OBS to the inbound course to avoid any confusion on which way to correct on that inbound course.

Sometimes a Hold In Lieu of PT (HiLPT) is used instead of a procedure turn, and is common on RNAV GPS procedures. The hold is used to orient the aircraft along the inbound course. The same rules about flying a PT apply to a HiLPT; you must fly the HiLPT unless one of the five cases listed above is true.

But how do you know if a HiLPT exists? After all, almost all approaches have a hold charted as part of the missed approach. That’s easy; if the hold is only for the missed approach it is printed in a dashed line format. If the hold is only for a HiLPT, then the hold is a solid bold line. And if the hold is used as both a HiLPT and a missed approach then it is also printed as a solid bold line.

ATC is expecting just the one entry turn within the hold. If you would like to do anything more than that, as above, you must get an agreement from ATC. If you need a second or third lap to get yourself ready, or just to lose some altitude, that should be fine, but ask first.

The same is true for the leg length. In the past almost all holds had one-minute legs. But with the advent of GPS, many holds are given with leg lengths of four, seven, or more miles. You should fly these lengths unless cleared by ATC for some other length.

Whether you use a traditional procedure turn or a HiLPT, the idea is to get yourself established on the inbound course. Doing so, generally speaking, is not very difficult. As always, pay attention to what is written on the chart and follow it. Also be sure that you are in a situation that requires a procedure turn. Once executed correctly the rest of the approach should be a piece of cake.

Ken Maples is a retired CFII in the mountains of Colorado where radar coverage is so sparse that procedure turns are done on nearly every approach.