If none of your vast experience involves a major international airport, it is incomplete. There are times when flying into a big airport is just more convenient, such as for a business meeting at the airport hotel or to pick up a passenger arriving by airline. With a little planning and study, you can handle even the biggest airports like an old pro.

Preparation

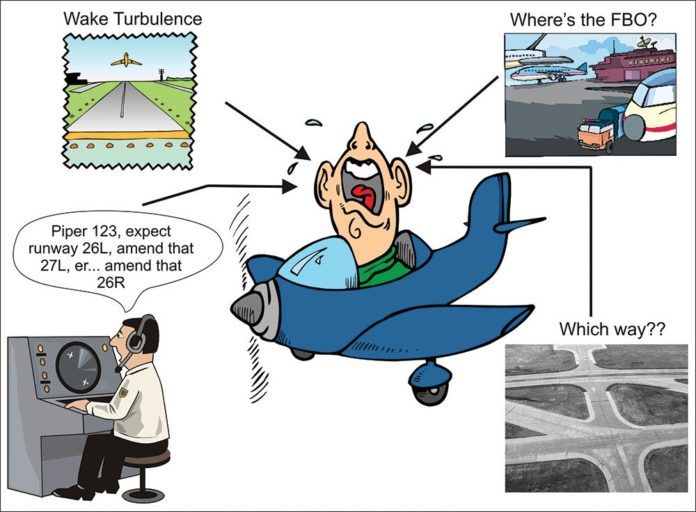

Start preparing by candidly assessing your basic skills. Do you sound like a pro or a trucker on the radio? Can you simultaneously understand, copy and comply with rapid-fire instructions? Do you know airport signage like the street signs in your neighborhood? Do you understand wake turbulence? Can you manage wide, long runways as well as short, narrow ones?

These minimum skills and knowledge are prerequisites before heading to BigCity International. For help, find a CFII who’s been there multiple times—possibly a retired airline pilot or one on furlough—and drill the basics. Consider taking the instructor along on your first visit to the zoo.

Next, study the airport diagram. Where will you park; how will you get there? Note all the parallel taxiways. These are often used as primarily one-way streets. Figure out the flow and how you’ll fit into it. Call the FBO to ask about fees or fuel purchase requirements. Do they even sell 100LL? Be sure you’ve got the latest charts arranged, either physically or electronically, into the logical order of use.

Phone the TRACON to discuss your flight. All the phone numbers you need are in the Airport/Facility Directory. Be precise and professional while you ask them what to expect. They have a wealth of information—the busiest times that you may want to avoid, runways you might expect, ground traffic flow and even specific taxi route predictions. Lacking that, you might be stuck waiting for release, holding en route or getting a scenic tour of the arrival or the airport after landing. Ask if you need an arrival or departure reservation.

Discuss the airport’s configurations—which runways are normally for arrivals and which are for departures. Determine which runway you can expect for arrival and departure. Note that wind is only a secondary consideration in runway selection. Expect up to 25 knots of crosswind and 10 knots of tailwind before they change the runways around due to wind.

Should you file IFR even in VMC? Yes. Avail yourself of the advantages of IFR getting lined up with vectors to final, eliminating all the confusion with multiple runways and taxiways. There’s no need for a Class B clearance. Finally, there’s no more certain way to be branded an interloper than to attempt VFR amongst the heavies.

Approach

You took the plunge. You’re expertly flying your clearance and got BigCity ATIS as soon as you could pick it up. About 40 miles out, you’re handed off to BigCity Approach. You check in with the ATIS and they tell you an approach and runway to expect. Big airports typically use just visual approaches and ILSes, but even on visual approaches, everyone flies the ILS path. Be ready for runway or approach changes, with the other charts and frequencies quickly at hand.

About 25 miles from the airport, ATC will issue radar vectors. Everybody else likely has final approach speeds between 120 and 145 knots. You’re probably the only aircraft flying double-digit short final speeds. Expect ATC to need time to find or make an arrival hole big enough for you. Also expect, “best forward speed” on long final. Life will be better for them and for you if you can manage 120 knots while gliding downhill.

Consider a minimum or even no-flaps landing, but practice these speeds ahead of time. Don’t forget to wait for proper gear and flap speeds in this unfamiliar speed regime. The bottom line, though, is that only you are responsible. Give yourself minimum but sufficient time to slow and properly configure for a landing in the touchdown zone.

With intersecting runways, you may be expected to keep your speed high on the roll-out to quickly pass the intersection or the ATIS may tell you to expect to land and hold short (LAHSO) of the intersection. Observe the arrivals preceding you and plan the same. You can decline a LAHSO, but if the big boys are doing it and you don’t, you may be vectored into a hold with an EFC of next month.

Wake turbulence should be a concern. In IMC, proper separation is maintained by ATC. But once on a visual approach, you’re solely responsible for wake avoidance. Fly a dot high on the glide slope and a dot upwind on the localizer (if parallel traffic permits). That’s another reason you should always plan to follow ILS guidance. Be aware of the wind and what it will do to the wake on approach and in the touchdown zone.

Once you see the airport, you may be overwhelmed by its size. Which of all the parallel concrete strips is your runway? Don’t fixate on the first one you see; look around and verify. Use the ILS and your moving map for guidance. Consult the airport diagram. Look for rubber scorch marks from landing aircraft, which often combine to look like fresh, dark asphalt. Be prepared for runway changes all the way to a few hundred feet AGL.

Landing

Major airports have high-speed taxiways exiting the runways, clearly shown on the airport diagram like freeway ramps, not intersecting streets. Keep moving onto the forward high-speed (never taking the reverse high-speed unless assigned) and onto the parallel taxiway. If necessary, you’ll get turns later to go the other way.

Once clear of the runway, keep your transponder on at airports with ground surveillance. (See note on the airport diagram or ATIS.) Be ready to copy rapid-fire taxi instructions and follow them. Here’s where a moving map airport diagram is worth its weight in gold. If you have a long taxi to the FBO you may be issued or request progressive instructions, but don’t expect the level of hand holding available at smaller airports.

The largest airports will have multiple Ground Control frequencies. ATC will typically assign new frequencies, but watch for taxiway signs telling you to monitor or contact another frequency. Note that “monitor” means to listen for them to call you, while “contact” means you should call them. Always repeat taxiway and runway names, explicitly repeat hold short instructions and always use your call sign in every transmission.

The controller may not use the name you expect for a runway. For instance, if you’re nearing the threshold of Runway 9L, you might be told to hold short of 27R. Also, if your route takes you through a ramp area there’s likely a ramp frequency which may or may not be on the airport diagram. Look for it on signs or a separate airport diagram page (usually in Jepps) showing ramp details before you ask for the frequency.

Don’t forget jet blast. Even a B-737’s minimum thrust to start rolling may exceed your rotation speed, so keep your distance and use proper control positioning to avoid being flipped.

Time to Go

It’s time to depart. To minimize your time as but one small mouse in a dance of the elephants, phone the tower and tell them realistically when you’ll be ready and ask when would be a good time to join the fray to minimize delays. Perhaps you can see the departure runway(s) from the FBO and there are more planes waiting than you can count? You might find it more comfortable and cheaper to enjoy the FBO a bit longer.

Do as much preparation as possible with the plane’s master switch off. Get ATIS and your clearance, if possible, by phone or a hand-held radio to avoid running the engine. Big airport ATIS will almost always be updated the last five minutes of the hour and will often use a computer voice that may be difficult to understand. Some airports—Denver is notorious—seem to update the ATIS every couple seconds, perhaps in response to a flea passing gas, affecting the wind.

Expect the departure runway whose heading is closest to your route, and is most easily accessed from your location on the ground, in that order of priority. Envision how the winds will affect wake from preceding aircraft. Consider doing your run-up in the ramp before calling for taxi as there may be no other opportunity, or do it while taxiing if your brakes and nerves are robust enough.

Keep communications succinct. Calling clearance, usually on a dedicated frequency, will be something like, “BigCity Clearance, Piper 123. HighPrice FBO, Information Zulu, clearance to SmallTown Municipal.” Once you’re ready to taxi, “BigCity Ground, Piper 123. HighPrice FBO, taxi with Charlie.” As before, your readback should be crisp, precise, explicitly repeating taxiway and runway assignments and should always include your call sign.

Your Take-Off

You’re holding short of your runway with Boeings and ‘buses departing. Don’t expect ATC to provide a wake turbulence delay. You may even be asked to depart immediately, but you can still avoid a wake encounter. Since you rotate well before the preceding departure, any turn should keep you clear of his wake. Although ATC expects departure turns at about 400 feet AGL, you can start as soon as you like. Sooner is safer for wake avoidance.

If you and the preceding departure have the same initial headings, you’ve got two things working for you. IFR (even in VMC) departures require more separation for consecutive departures in trail than if they diverge, and you are more agile and can safely side-step upwind a bit, even in a turn, assuming you won’t encroach on parallel runway operations. The only time you can’t stay upwind is if the turn you both get is a downwind turn.

Be sure to tell ATC of your side-step plans as you take the runway, “Piper 123, BigCity Tower. Runway 27L, line up and wait.” And you’d reply, “Line up and wait, Runway 27L, and be advised after take-off we’re planning a side step of a few hundred feet to the left for wake avoidance. Piper 123.” Repeat your intentions reading back your take-off clearance, “Cleared for take-off, Runway 27L, with a left side-step. Piper 123.”

If there’s no way you can avoid the preceding wake in light winds, consider requesting a delay as soon as possible. Remember you’re PIC and the sole responsibility for a safe flight is yours. It’s your obligation to decline any clearance if you think it will put your aircraft in jeopardy, an obligation I once exercised in exactly this situation.

Flying into a major airport can be a challenging and rewarding experience that takes some study, planning and practice. Being able to make full use of these airports increases your utility and can complete your experience base. It gives you bragging rights, too.

Big Airports, Big Bucks

While business jets are big airport FBO’s bread and butter, staff will usually go out of their way to make everyone feel especially welcome, even the piston single pilot. The FBO offers services like flight planning lounges, coffee and snacks, fuel, maintenance and even courtesy ground transportation, especially to and from the terminals.

Major airports can be expensive. Fly into JFK in a C172 before 3:00 PM and you’ll pay a $25 landing fee, a $70 parking fee for eight hours and a $32 facility fee—waived with the purchase of seven gallons of avgas that can hit $10 per gallon or more—all collected by the FBO. Fly in between 3:00 and 10:00 PM and the landing fee rockets to $114.

If you’re flying in for fun and don’t even need to park, some towers (including JFK) may allow you to simply taxi back for departure, picking up a clearance on the way. Call the tower in advance to discuss this option, but avoid the busy times. —DB

Douglas Boyd, Ph.D., is a commercial, instrument, multi- and single-engine pilot, a FAAST representative and an Aerospace Medical Association Safety Committee member. He risks life, limb and aircraft by regularly flying into Houston Bush Airport.