Most pilots have heard at some point that ATC separates aircraft on a first come, first served (FCFS) basis, but have experienced the opposite. Many of us pay for our aircraft by the hour, so it’s understandable to get impatient when you’re first up and Tower tells you there will be others ahead of you. Nearly every day when I’m working Tower I’ll hear, “Uhhh, Tower, N12345 is still ready for departure,” (when passed up) or even a quick, “Tower, N12345 was first…” It’s not the pilot’s fault.

Operational Priority

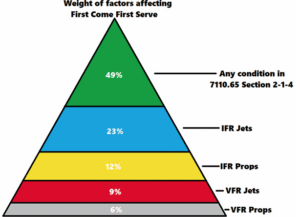

Determining who gets to do what and when, while largely driven by FCFS also must be decided with the big picture in mind. The main reasons are actually lined out in the 7110.65, section 2-1-4 “Operational Priority.” As controllers, this is the very foundation on how we start to prioritize the mentality of FCFS. Some of the many factors that might “adjust” a pure FCFS schedule include: aircraft type or status (Medevac?), IFR or VFR, route, weather, flow, workload, etc.

Of course, there’s the ultimate priority: “An aircraft in distress has the right of way over all other air traffic” as outlined in §91.113(c). If at any time you experience distress, whether you declare an emergency or not, you become priority one as soon as ATC knows about it. There is no hard altitude, speed, direction, etc. Simply put, it’s “get on the ground the fastest and safest way you can.” An emergency is not considered normal air traffic, thus it gets priority.

So, if there’s no immediate danger of loss of life or property, logically the next priority would go to Medevac flights. Any flight that says they are Medevac gets a step up in any line, to a point. From a departure standpoint, they go directly to the front assuming they can reach the runway. On arrival, they would normally get direct to where the line into an airport starts; if there’s no traffic, it’s just direct to the field.

The other items in 2-1-4 pertain to “priority” of presidential aircraft, SAR (Search and Rescue) aircraft, interceptor operations and some obscure situations. In the Tower where I work, we don’t get a lot of these. Obviously if we see one coming in or moving around, we’ll give priority as required.

Priorities…

So, ATC’s priority is FCFS, but with a lot of exceptions and interpretation. One point I try to make is that there is a much bigger picture that pilots often can’t see. For one simple example, a ground delay program at a destination might require varying departure order well outside of FCFS—you certainly wouldn’t want departures being held up with a guy at the head of the line who’s waiting 30 minutes for his destination to open up.

Let’s walk through some of the considerations that affect who goes and who waits. The first item: Is the aircraft arriving or departing? If one of each calls, who goes first? I’m looking at how far out the arrival is, how fast they are going, the type of aircraft departing, if they are IFR with a release time, etc.

If both aircraft are VFR, it’s simply a matter of aircraft types and speeds. If I have a 172 coming in to land four miles out, and a PA28 ready to depart, there is not really any issue. I’d clear the PA28 for takeoff and then clear the 172 to land and let him know that traffic will be departing prior to his arrival. So where is my cutoff as to who goes first? In this scenario, probably about a two-mile final and I would hold the PA28 until the 172 lands.

So, all other things notwithstanding, the only way the arrival has me holding the departure is if any of the conditions we talked about before, now apply. If a G7 is on final vs. a Cherokee that wants to depart, all I determine is if there is enough space based on the speed of the G7. If they are going 180 knots (ground speed) and on a four-mile final, I could clear the PA28 for immediate and tell ’em to “move it!” If the G7 is on two-mile final, regardless of speed that Cherokee is holding short.

So, all other things notwithstanding, the only way the arrival has me holding the departure is if any of the conditions we talked about before, now apply. If a G7 is on final vs. a Cherokee that wants to depart, all I determine is if there is enough space based on the speed of the G7. If they are going 180 knots (ground speed) and on a four-mile final, I could clear the PA28 for immediate and tell ’em to “move it!” If the G7 is on two-mile final, regardless of speed that Cherokee is holding short.

If the departure is part of any ground-delay program and it’s time for him to depart, I as the Tower controller have to do everything in my power to get him out at the specified time. That might not look like FCFS to other pilots, but that ground-delay program might have already had the departing aircraft ready a long time ago. If I can’t get them out within the established window, I risk delaying the aircraft hours—again. Luckily, those “expect departure clearance times” (EDCT) have five minutes of slop. An EDCT probably wouldn’t affect the departure if it was only one arrival I was concerned with. Add two or three more arrivals, then I really have to hit—or make—holes in the arrival stream.

So, let’s change the scenario up to another common FCFS problem—departures only. Let’s say I have an IFR G7, IFR C560 with EDCT, IFR T210, and 2 VFR 182’s. They all taxi to the end in that order and call ready one right after the other (Yes, this happens—enough that I wonder if the pilots plan it!). I’m looking at the EDCT time before anything else, even though they called second. If it’s within five minutes of the EDCT time, that C560 is going first and I won’t even try to get anyone else out. The second I try to get any other departure out, I run the risk of something happening or taking too long and missing my window. The order would be the IFR C560 with EDCT, G7, T210, then 182s unless I can squeeze ’em out in between.

If I had time on the EDCT, the G7 would be first, then T210, then 182s and C560 as appropriate. See how that little detail changes my entire flow? Also, my flow would be based on whatever Approach Control gives me, or doesn’t give me. If there is any training in progress on the other side of the shout line, my releases could take a while, so if I have no releases or other reason to hold my VFR 182s, they go first despite calling last. On a normal day, the T210 will be the last airplane to go unless the G7 had to wait for a departure gate to open or weather to move.

appropriate. See how that little detail changes my entire flow? Also, my flow would be based on whatever Approach Control gives me, or doesn’t give me. If there is any training in progress on the other side of the shout line, my releases could take a while, so if I have no releases or other reason to hold my VFR 182s, they go first despite calling last. On a normal day, the T210 will be the last airplane to go unless the G7 had to wait for a departure gate to open or weather to move.

Scenarios are endless, but you see that a tiny detail could mean the difference between you going first because you called first, or going second or even last because of reasons beyond your control, or even mine.

The Last Shall Be First…

Appearing to be forgotten happens when you are the first to taxi out but the last to leave. As we’ve discussed, there are many different factors that throw the sequence off, but the controller continuously has to play “What If” and get all aircraft moving as efficiently as possible. I like to think of First Come, First Served to be just like the aircraft it serves: lots of moving parts that vary output based on conditions. Regardless of the sequence you’re assigned, rest assured that the controller knows you’re waiting and he or she is doing everything safely and efficiently possible to get you on your way. Fly safe.