Receiving my instrument ticket from a university pilot-mill, flight and weather planning was grueling and intense. For flights over an hour, a Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (TAF) is used. For secondary airports within five miles of a field with a TAF, the TAF from the primary airport can be used No TAF? Use the Area Forecast (FA).

This originated from the Aviation Weather Services advisory circular, which states that an FA is used “to interpolate conditions at airports which [sic] do not have a Terminal Aerodrome Forecast.” Determining forecast weather, particularly ceilings and visibilities, is essential for instrument pilots to ascertain if an alternate is needed and to select one that meets requirements.

Last summer, the FAA and NWS slipped a notice into the Federal Register announcing the 2015 end of the FA. After 80 years of faithful service, the feds don’t see the value in it anymore. They argue that the information in an FA can be replaced by products that provide similar information with greater specificity.

Granted, the FA isn’t perfect with its cryptic abbreviations, broad coverage and long view. But, the FA is immensely valuable to GA instrument pilots, providing information currently not available in any other forecast. Let’s look at our options.

Following the Law

Only two regs specifically deal with weather forecasts: 91.103 (preflight actions) and 91.169 (IFR alternate planning). The forecast a pilot should use is not disclosed in the reg. Instead, it states that a pilot use “appropriate weather reports or weather forecasts, or a combination of them.” (Emphasis added.) What is appropriate?

The feds have not defined it for Part 91, nor have they prescribed what forecast product should be used. We do know, however, that it’s a good idea to use something produced by the National Weather Service in the event the feds take a closer look at your flight planning.

Regulations and case law define “appropriate” for commercial operators—a TAF is required. For example, 135.213 states that weather observations for IFR operations must be taken at the airport, precluding the use of an FA.

The FAA and NWS develop TAFs based on passenger enplanements, number of operations, and funding limitations. This means that Grassy Knoll Muni with 27 operations a week, ain’t gettin’ a TAF anytime soon.

Replacement Needed

With no requirement to use a specific forecast, a product that provides necessary information for IFR flight planning is needed. Specifically, the forecast must differentiate between ceilings of 600, 800 and 2000 feet and visibilities between two and three miles. These are the important numbers for determining if an alternate is required and if appropriate weather exists at an alternate. Of course, it must also provide sufficient time granularity.

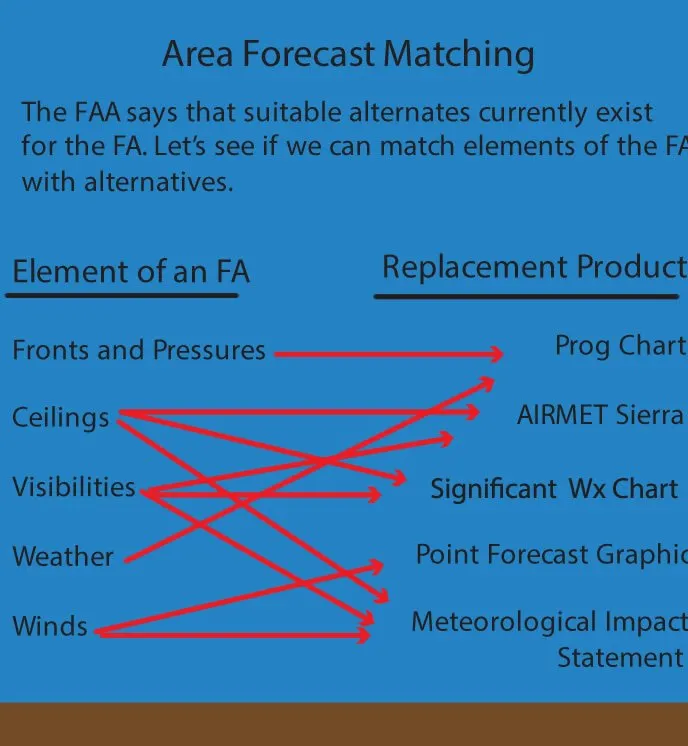

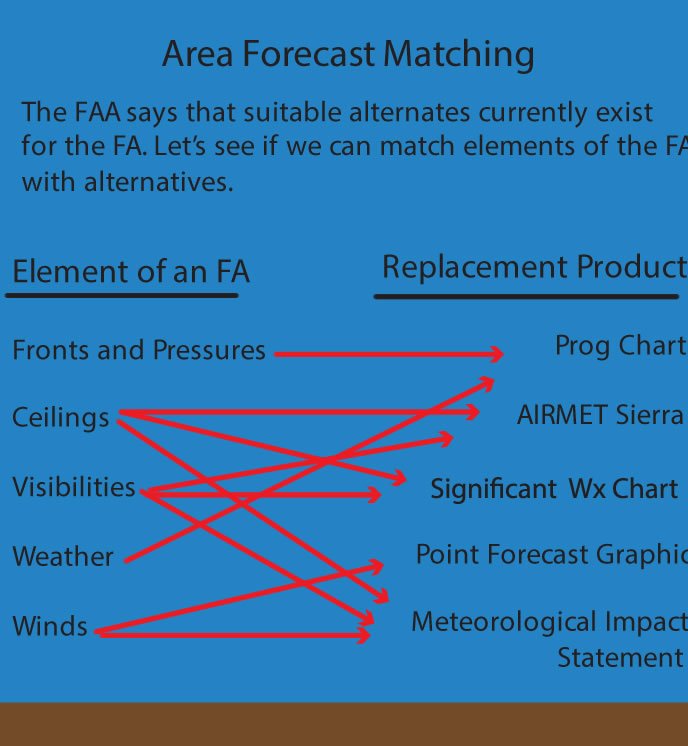

In their entry in the Federal Register, the FAA and NWS supplied a list of FA substitutes; surface weather analysis charts, prog (prognostic) charts, significant weather charts, TAFs, and AIRMETs (airmen’s meteorological information). These serve as a starting point.

The surface analysis chart, although informative, can be tossed right away because it reports current conditions, not a forecast. Prog charts are forecasts, but don’t provide ceiling or visibility information. A TAF does contain everything needed, but is not a replacement for an FA since it is airport-specific. That leaves significant weather charts and AIRMETs as suggested alternatives.

Low Level Significant Weather charts provide weather between the surface and flight level 240 issued in 12- or 24-hour forecasts. The charts identify areas of marginal VFR and IFR, which is defined as a ceiling between 1000 to 3000 feet and/or visibility between three to five miles and a ceiling less than 1000 feet and/or visibility less than three miles, respectively. While this provides information on ceiling and visibility, it is not what’s important for instrument flying. Marginal VFR may or may-not require an alternate and IFR may or may-not be suitable weather at an alternate.

This leaves AIRMETs. AIRMET Sierra describes IFR conditions and mountain obscuration. Criteria for issuance of an AIRMET Sierra are a ceiling less than 1000 feet and/or visibility less than three miles. This is similar to the significant weather chart in that it indicates areas that meet the criteria but doesn’t provide necessary detailed ceiling and visibility numbers. Besides, AIRMETs aren’t designed to forecast terminal weather. According to the FAA’s Aviation Weather Services, AIRMETs are designed to identify “enroute weather phenomena.” (Emphasis added.) AIRMETs also have the problem of being more abstruse than an FA when describing location.

More Options

Other useful products, although not identified by the feds, are the Meteorological Impact Statement (MIS), Aviation Forecast Discussions (AFD) and Ceiling and Visibility Analysis (CVA). An MIS is issued for forecast weather that will affect ATC. This includes low ceilings and visibilities with heights and distances, heavy rain and strong winds. Unfortunately, this product is aimed at ATC, is hard to find, and only issued when needed. The AFD allows a weather forecaster to expand on conditions associated with a TAF. Tim Vasquez, IFR’s resident meteorologist, gobbles this stuff up. Although interesting, the format is not standardized and is concerned with weather influencing TAFs—not a good FA replacement.

The CVA supplies a quick overview of ceiling and visibility conditions. A cool feature of this product is that it estimates conditions between reporting sites. Therefore, if an airport you fly to doesn’t have a METAR, the CVA can be used to get an idea of conditions. Unfortunately, the product is based on observations and isn’t a forecast.

This leaves no good replacement for the FA. If the FA disappears without a replacement, using current products would burden pilots by requiring the filing of alternates when not needed—because the ceilings and visibilities aren’t sufficiently differentiated—or using airports with TAFs.

Beyond Ceilings and Visibilities

There’s more to an FA than ceiling and visibility information. Area forecasts also contain information on weather and wind. Weather data is included when it reduces visibility. Forecast winds greater than 20 knots or gusts greater than 25 knots get reported. This information is important for flight planning and determining the suitability of airports and approaches.

Prognostic charts can replace weather info contained in FAs. Depicted weather includes rain, snow, thunderstorms, showers, drizzle, freezing rain, sleet, fog and haze. Areas of weather are conscribed by green lines and shaded if the coverage is between 50-100%. Combining prog and significant weather charts allows a pilot to correlate conditions that cause reduced ceilings and visibilities.

An option for winds is the National Weather Service’s Point Forecast graphic. This is found by navigating to weather.gov, inputting a location, then selecting “Hourly Weather Forecast Graph.” The graph provides a 48 hour forecast of temperatures, dew points, surface winds, sky cover, and more. The product is a nifty tool for checking wind and other conditions. But, it isn’t included in DUATS, ADDS, or a standard weather briefing, it takes some work to find, and viewing it isn’t recorded in the event something goes awry.

Promises, Promises

Something is wrong when it takes a gaggle of products to ineffectively replace one. Undoubtedly, the FA isn’t perfect; any product 80-years old needs some revamping. Nonetheless, abandoning it instead of updating it is a mistake.

The FAA wrote in the Federal Register that aviation users are already accustomed to consulting weather products that provide similar information to an FA using higher resolution and graphical depictions. That just isn’t true.

Current products use a similar 12-hour forecast period with less specificity about ceilings and visibilities. Inarguably, location descriptions of AIRMETs are worse than those used in the FA, although G-AIRMETs can help some.

The Feds promised a formal safety risk assessment before ditching the FA. This may be of little help for GA where little user data exists and alternate planning does not appear to be a problem.

Regulations burden an instrument pilot with determining alternate requirements. If conditions are forecast less than a 2000 foot ceiling and/or three miles visibility for an hour before to an hour after the estimated time of arrival, an alternate is required. Weather at an alternate must be greater than 600-2 or 800-2 depending on approach. If TAFs are not available, the best option, and the one recommended in Aviation Weather Services, is to use the area forecast. Suggested alternatives for the FA lack specificity and serviceability.

This leaves the post-FA instrument pilot in a conundrum when operating to airports without a TAF. An AIRMET sierra for IFR conditions, or significant weather charts showing MVFR or IFR will require filing an alternate. Weather at an alternate must be better than IFR, even though it may actually be above regulatory requirements.

Hopefully the Feds will wise up and realize the FA needs updating, not eliminating. Getting rid of the character limit and producing it in plain language would make it much more usable. Creating a graphical equivalent would also be useful. Current options for replacements just don’t measure up.

Jolting awake asking, “Who took my area forecast?” is a recurring nightmare for Jordan Miller. He maintains a CFII and flies for a major airline.