The flight to your vacation destination ended a few miles short with an unplanned overnight in Virginia. The trip started from home base in Minnesota and included an unexpected icing encounter followed by a closed runway that required a diversion. By contrast, it’s an uneventful start early the next day to fly VFR with your spouse to Roxboro, North Carolina, (KTDF) yesterday’s original destination. From there, with two more passengers, you’ve got a full load. But no matter; it’s vacation. And the modestly upgraded panel will get you anywhere you’d want to go.

The Route

The week-long holiday will start in earnest at St. Simons Island, Georgia, a bit south of the better-known Hilton Head Island. Assuming direct from KTDF to KSSI will be unlikely in this busy area, you check recent filings and find:

SDZ V3 FLO V437 CHS V1 TYBEE

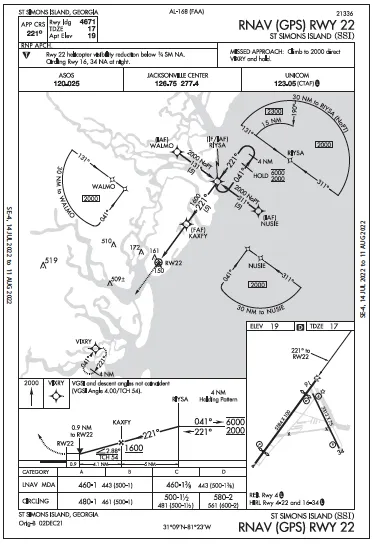

Fair enough. Just enter that routing into the EFB. This’ll answer two questions: Where does the route take you, and what’s the time penalty? After BASSO, 25 miles past CHS, the route starts to head out over water, as much as six miles from the shoreline. That’s not too far, but you file for 8000 feet instead of 6000. And the time penalty’s insignificant; the route adds only three minutes to a 2.5-hour flight and less than a gallon of fuel. Better yet, The Charleston VORTAC is nearly straight-in for the RNAV 22. A 125-mile final does sound fun. And at any rate, direct-to would’ve threaded the needle between two military operations areas, but then plowed through the Beaufort 3 and 2 MOAs, requiring a reroute.

The only other caveat now is that while the shoreline flight offers a terrific view, there’ll be enough cloud layers to obscure that. The en-route forecast indicates stable cloud layers between 3000 and 5000 feet. But as it’ll clear up in a few days, you can request the same route on the return flight. Now, the destination has great visibility while ceilings will remain a bit lower at 2000 feet, so you don’t need to file an alternate. (14 CFR §91.169 says so if “at least 2000 feet…”) But unofficially, you put Bacon County Airport in Alma, Georgia in the back pocket as it’s further inland with just a few clouds at 3000 feet, 10 miles’ visibility.

IFR “Minimums”

Just about ready to start up. Wanna save a few minutes and get the IFR clearance in the air? You’re well outside the Charlie airspace of Raleigh-Durham International and at a non-towered airport, so it’s an option. You can climb VFR above the 2000-foot scattered layer until cleared to the expected IFR altitude of 8000 feet. But with the clouds close enough to make VFR climbing a bit tedious, you opt for the phone call to Raleigh App/Dep using the phone number in the Chart Supplement. Expect a void time, and you’d have at least 10 minutes to depart; that’s more than plenty.

The clearance is “as filed,” followed by “hold for release.” You mention that you can be off in about 10 and inquire about any delays. You get a general reply that they want to know when you’re holding short of the runway (they like to know which one) to fit you into the flow. That means you’ll need another callback to get that release after the pre-takeoff checks are out of the way.

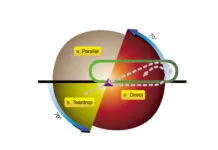

Since the call-ahead wasn’t a time-saver, it’s mighty tempting now to switch things up and just launch VFR. You’ve got the clearance, it’s VFR there and you can call Departure airborne. Happens all the time. Well … yeah, but you’ve scraped up a little hole in the plan. As the AIM (5-2-7) states: “The ATC instruction, ‘hold for release,’ applies to the IFR clearance and does not prevent the pilot from departing under VFR. However, prior to takeoff the pilot should cancel the IFR flight plan and operate the transponder/ADS-B on the appropriate VFR code. An IFR clearance may not be available after departure.”

So if you take a minute to “undo” the IFR flight plan (via touch-screen? A phone call?) and squawk 1200, depart VFR like you planned, and … hope for a quick clearance? At this point, you could keep digging at the hole while possibly losing more minutes, or just call back for release.

By the way, the AIM closes its explanation of release and hold times with this: “If practical, pilots departing uncontrolled airports should obtain IFR clearances prior to becoming airborne when two-way communications with the controlling ATC facility is available.” Most places don’t have reliable two-way radio reception with the controlling departure facility and that’s what the published land line is for.

At the very least, it’s usually preferred and never a bad idea to get the clearance (not to be confused with the release) while on the ground. While legal and sometimes necessary, getting clearances in the air are best done outside of crowded airspaces. So from the runway hold line you call back and get airborne within a half minute.

Stay in the System

It’s a smooth flight and before you know it, you’re over Charleston. The ceilings in the area are about as forecast, 3000 feet broken, tops around 5500 feet. If you did decide to descend below to get a better view of things (and start looking for St. Simons), you could request an IFR descent, then cancel. Fly the planned route VFR, using altitudes as you like along the shoreline. Fly the RNAV 22 to SSI as you would IFR for a stable approach.

But cancelling means you’d need to fly at least 500 feet below the bases. That’d still be 2500 feet, higher than what’s required for the approach; the minimum stepdowns are 2000, 1600 then to the MDA of 460. The land below is right about sea level. After RIYSA it’s over land, with an Off-Route Obstruction Clearance Altitude (OROCA) of 2700 feet. Flying with GPS and over water, you’re not concerned as any significant obstacles are inland. Perhaps this part could be achieved VFR, but only if ATC continues flight following.

Or stay IFR. Then how low could you go, and will it get you into the desired VMC? The Minimum Vectoring Altitudes are in the realm of 2200-2500 feet and, like the other IFR altitudes, offer the default minimum obstruction clearance (1000 feet in non-mountainous areas) while in radar contact. For the second time today, you refrain from flipping the VFR switch. This can wait until closer to the airport.

So get an easy letdown approved to 2800 feet, followed by a request for the straight-in RNAV 22. ATC doesn’t care whether it’s a visual or instrument approach clearance; either is still under IFR. Flying the latter is an LNAV-only approach, so you’ve gotta figure out the descent.

This runway has a VGSI in the form of a two-light PAPI—non-precision. Meanwhile, the approach profile view says the VGSI angle is a four-degree glidepath “not coincident” with the IAP’s much shallower Vertical Descent Angle of 2.88 degrees to a threshold crossing height of 54 feet. Keep in mind that VGSIs are all advisory (see AIM see 5-4-1) and you’re glad to have a great view of the shoreline along with the runway visual cues you begin to see on final.

Even better, that modestly upgraded GPS provides advisory descent rates for a final distance of your choosing, which can be cross-checked with the VSI (you still have the round gauge for that). You did know that the default three-degree glidepath (close to the published 2.88 degrees) flown at 90 knots groundspeed means a descent rate of 478 feet per minute. You’re comfortable up to 700 feet per minute on a two-mile final, and see that the descent calculation for a 4.5-degree path is 715 FPM.

The descent on this approach can easily stay below four degrees, and while there is a significant displaced threshold of 913 feet on Runway 22, there’s 4671 feet of declared landing distance shown on the chart. That’s still plenty even if you fly the final approach slightly high while keeping the descent to about 600 FPM.

It’s too busy now to cancel in the air, so you just accept a frequency change to CTAF. The touchdown was indeed a tad long, past the first taxiway, but still about a third of the way down, mainly because you were too busy on short final to deploy the last notch of flaps. No problem; just don’t forget to call Center to cancel via air-to-ground (126.75) or, better yet, the land line, after parking.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She regularly combines IFR and VFR, flying instruments on weekdays and visuals from a grass strip on weekends.