If there was ever a 400-pound gorilla that dared pilots to ignore their checklists, procedures and situational awareness, it’s the emergency. Pilots often practice “What if …” but when it really happens it’s more like “What the hell?” If there was ever a time to lean on ATC, this is it.

There are no limits to the types of emergency scenarios and, therefore, no single response from ATC. The ATC rulebook (FAA Order 7110.65) recognizes this in paragraph 10-1-1 (d): “Because of the infinite variety of possible emergency situations, specific procedures cannot be prescribed. However, when you believe an emergency exists or is imminent, select and pursue a course of action that appears to be most appropriate under the circumstances.”

We controllers have extensive information, resources and people at our disposal, but we’re out of the picture unless you tell us what’s going on and ask for what you need.

Shout Out

Imagine: You’re walking down a street and hear a sudden cry for help. Questions fill your head. “Who’s in trouble?” “What’s wrong?” “What do they need?” The same goes through a controller’s mind. We’re required to immediately ascertain three things from an aircraft in distress: the callsign, the nature of the emergency and the pilot’s desires.

The official phraseology for declaring an emergency is simple: broadcast “Mayday” or “Pan-Pan” three times, as specified in AIM 6-3-2. Or just state, “I’m declaring an emergency.” Each method should cause anyone on the frequency to shut up and listen. Note that ATC’s rules make no real distinction between “Mayday” or “Pan-Pan.”

Include as much information as you can in that first transmission. A “by-the-book” emergency call could be, “Mayday, mayday, mayday. Cherokee Six Eight Charlie declaring an emergency. I’ve lost oil pressure 10 miles east of Charleston, descending out of 6000. Three souls on board. Three hours of fuel. Squawking 5712.” That’s the entire situation in a nutshell.

But you don’t need to even say “mayday” or “emergency.” Controllers are generally good at reading between the lines, and are encouraged to do so by 7110.65 10-1-1 (c): “If the words ‘Mayday’ or ‘Pan-Pan’ are not used and you are in doubt that a situation constitutes an emergency or potential emergency, handle it as though it were an emergency.” That last sentence gives controllers the right to declare an emergency on behalf of a pilot.

There are many trigger words: “Engine failure,” “hydraulic failure,” “lost pressurization,” and “unconscious passenger” are just a few. There’s also the sphincter-tightening “fire” or “smoke.” Any of those things could drive a controller to initiate an emergency response. If any doubt remains, ATC could outright ask, “Are you declaring an emergency?”

It’s Your Call

Yes, ATC’s chief concern is the pilot’s safety. Nonetheless, the final authority for the airplane lies with the aviator. If ATC somehow influences the pilot’s actions and inadvertently worsens the situation, the controller can be held responsible for the accident. Consequently, most controllers are reluctant to issue instructions without a prior request from the pilot.

If you’ve declared an emergency and that voice over the radio is asking you to “Say request,” remember he can’t see inside your cockpit. Use your best judgment, assess your situation properly and speak as clearly as possible. Don’t worry about phraseology—use plain English as needed.

Information and vectors are two of the most common things pilots request when under duress.

Pilot: “Lost my starboard engine. Where’s the closest airport?”

Me: “The nearest field is six miles away on a heading of 220.”

Pilot: “Fuel’s real low and this weather’s not giving up. Looks like I’ll be needing to make an unplanned stop here, but I don’t have charts for your airport.”

Me: “I have the approach chart here; let me know what information you need.”

Pilot: “Hit a pocket of turb so nasty I broke my friggin’ headset on the ceiling. I need to get out of this cloud deck.”

Me: “I just asked an aircraft four thousand feet below you for his flight conditions and he said he’s in VMC. Want lower?”

Don’t forget we have ready access to a telephone. If you have an unconscious passenger, we can have an ambulance ready when you land. If you autorotate your crippled helicopter into a farm field, we can record your location, get county fire and rescue services rolling and even notify your company office (if we know who to call).

The five scenarios I just listed aren’t theoretical. They are all real distress situations I’ve been involved in—either talking to the pilot or helping in the background—in the past six months.

Needle in a Haystack

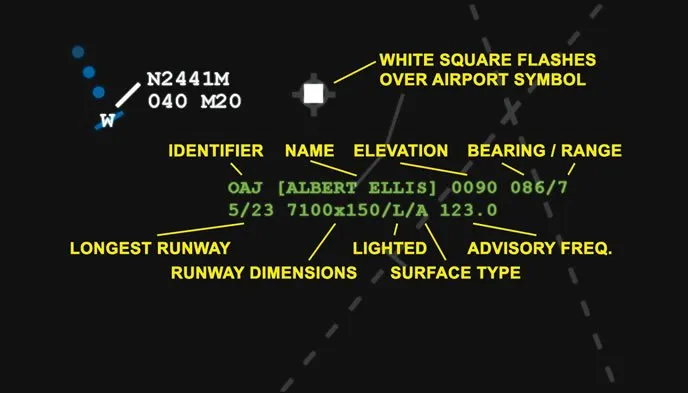

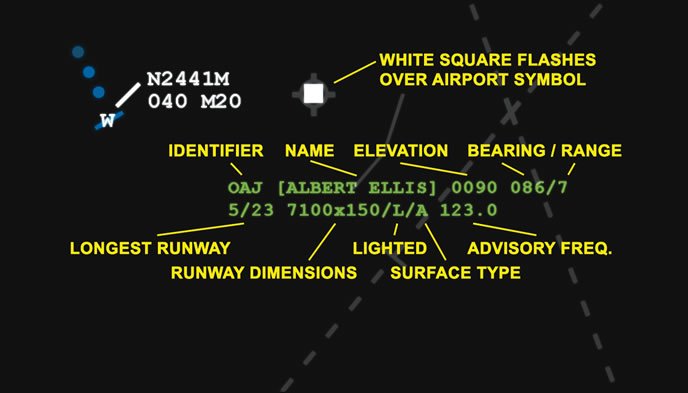

Determining the aircraft’s position and altitude are the first of many questions to follow a declaration of emergency. If you’re in current visual or radar contact with ATC, we already know this part.

Now, what if you departed VFR on your own and hadn’t yet talked to ATC when the crisis occurred? Or, what if you can’t raise the ATC facility right away? Broadcast on 121.5 and squawk 7700. That code will set off audible alarms in all ATC radar facilities in range.

Be aware that all ATC facilities monitor 121.5. Depending on your altitude and area radio coverage, every one of them for hundreds of square miles could potentially hear you. The controller who responds may not be anywhere near the airspace in which you are flying and may need some detective work to figure out your position. If he’s unfamiliar with any of the fixes you’re referencing, use major airports, cities or geographical features to help him narrow the search for your target. For instance, use “30 miles northwest of Miami” instead of “over WINCO intersection.” The intent is to figure out which ATC facility can best serve you.

ATC will also request the type of aircraft, number of souls (people) on board, and amount of fuel remaining in time. While the fuel amount inquiry of course dictates how much time aloft remains, it serves a second purpose. The grim reality is rescue personnel need to be prepared for the worst case scenario—a fiery crash—and kept abreast of the crisis’ scale. A Boeing 757 with four hours of fuel and 193 people aboard will potentially require a much larger response than a Piper Cherokee with two hours of fuel and two souls on board.

Subsequent questions can go many directions depending on the nature of the emergency. AIM 6-3-2 provides a comprehensive overview of information that can come into play.

Dividing the Load

The pilot isn’t the only one calling for help during an emergency. Controllers are quick to call for backup.

Emergencies aren’t exactly scheduled events. A controller may already be under pressure from heavy traffic and the added stress of the emergency may send him down the crapper. Overloaded ATC isn’t effective ATC, so other controllers, supervisors and support staff step into the mix and divide up the workload.

Having extra sets of eyes and ears reduce the chance of a detail being missed. While the pilot in distress may only hear that one voice on the frequency, the other folks assisting behind the scenes are notifying airport rescue services, giving the heads-up to other affected sectors within the same facility, contacting other facilities down the line that will work the stricken airplane and brainstorming solutions for the crisis.

If the aircraft lands off-airport, search and rescue operations are initiated by the United States Air Force Rescue Coordination Center in Tyndall, Fla. Local police and government agencies are alerted of the airplane’s last observed location. If the downed aircraft’s location is unknown, SAR flights from entities such as the Civil Air Patrol and Coast Guard attempt to home in on it via its ELT.

Once the emergency ends, the paperwork begins, at least for us in the radar room. ATC facilities keep logs of the emergencies in which they are involved. All radar feeds and voice communications are also saved in case an investigation does result, and internal quality assurance reviews can be conducted to ensure that everyone did their job correctly. The Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) is likely to get involved as well and may request at least a statement from the pilot. Things may, or may not, progress from there.

Generally speaking, the larger the aircraft, the greater the damage to lives and property, and the more severe the type of emergency, the more likely there will be a formal investigation.

Above the Law

No discussion of emergencies is complete without emphasizing FAR 91.3: “In an in-flight emergency requiring immediate action, the pilot in command may deviate from any rule of this part to the extent required to meet that emergency.”

That reg permits you to deviate from all ATC instructions if the situation demands it. Only a small minority of controllers are pilots. The voice on the radio may not understand that your engine-fire checklist says dive to attempt to blow out the flames, that losing your vacuum pump in IMC leaves you without an attitude indicator or DG, or that a turn towards a dead engine is a bad thing. Use your judgment and listen to your self-preservation instinct. If you don’t have time to communicate, act first and explain yourself later. You legally have final word. After all, it’s your life on the line.

“They’re safe on deck,” are some of the best words Tarrance Kramer has ever heard while working traffic in the southeast U.S.