Call it the familiarity trap. When planning a new route or destination, you carefully examine the charts, procedures, airport diagrams, and approach minimums. But you tend to skip a lot of these steps on well-worn routes and at your home ‘drome. It’s near-certain that you’ll eventually discover how this complacency can be a big gotcha.

From your home base at Fulton County Airport in Wauseon, OH (KUSE), you in your SR20 and a buddy in his Cherokee Six plan to fly to Warren County in Lebanon (I68), where he’s dropping off his bird for an annual.

Since you’re both busy the next morning, you plan the dropoff the evening before. It’s early spring with some marginal VFR, so you file identical IFR flight plans with basic RNAV equipment. You’re both current and comfortable for night IFR and have flown to I68 many times. You file in sequence with a 15-minute gap, and go just after sunset.

Winds are from the southwest at 15 to 20, so you depart Runway 27, planning a straight-in from the RNAV Runway 19 at I68. The 128-mile flight takes the Cherokee just under an hour and about 10 minutes less in your Cirrus. It’s a short out-and-back; piece of cake.

Forgotten Notes

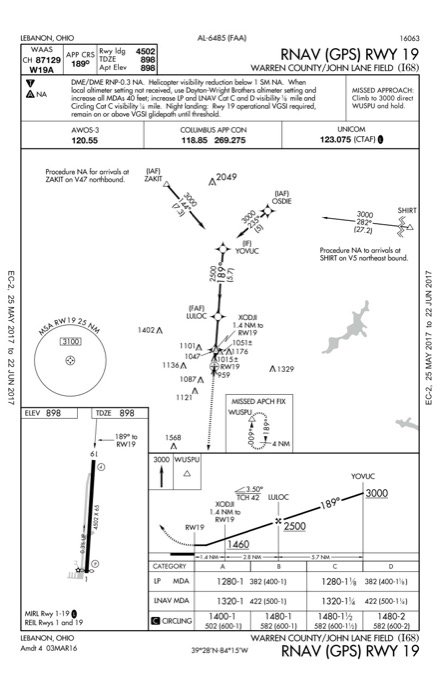

En route, you load the Lebanon RNAV 19 approach on your (non-WAAS) GPS. Before you talk to Columbus Approach, you’ve tuned in weather and CTAF and are ready for direct OSDIE for the approach. With night arriving and a thin broken layer at 2300 feet, you’ve asked to fly the full procedure and plan the LNAV MDA of 1320 feet.

When we’re flying a familiar approach we’ll likely review the approach itself (fixes, altitudes, courses, distances, minimums, etc.), but we tend to skip over the notes and maybe even the missed approach procedure.

This is exactly what you do about 25 NM from OSDIE. You’re unaware of the trap you’ve just set. The RNAV 19 approach includes lengthy print notes that you’ve safely ignored many times due to your familiarity. Besides, it’s dark and you don’t have time to go heads-down with a red map light right now. You’ve been cleared for the approach at I68, received your handoff to advisory, and are a minute from OSDIE.

It’s all good until a mile from LULOC, the final approach fix. You see some dim lights ahead but not the PAPI you’re expecting to make sure you’re not drifting too low as you descend to the runway in the dark. You click the mic a few times, but nothing. Still, you’re okay just following the stepdowns, descending from the FAF to 1500 feet before XODJI and staying at 1400 feet (500 feet AGL) until you’re a mile out.

You forgot to cancel IFR on final, so you call on the ground. The Cherokee arrives right on time and you both depart in the SR20, with Columbus Departure already waiting to hear from you. The night skies have cleared by now and a visual approach clearance is all you’ll need to get back home.

The Fine Print

Just as you’re relaxing at 7000 feet with an easy arrival ahead, your buddy says, “I couldn’t turn on the PAPI. Could you?” You tell him you also had no luck and simply continued the approach. Then he says: “I saw a note on the approach that you need the PAPI, so I cancelled IFR before LULOC and just followed the approach on my own.” You pause to absorb this, then both agree you might have goofed; perhaps you’ll cap off the evening filing ASRS reports.

Back home, you finally read the notes on the IAP. There’s some stuff about DME, then a note on helicopter visibility, which you skim over, and then there’s something about using another field altimeter setting if the one at I68 is unavailable on the AWOS. You already had the weather at the field and upon confirming that your aircraft is fixed-wing, you move on to, “Night landing: Rwy 19 operational VGSI required, remain on or above VGSI glidepath until threshold.”

You dig to remember that VGSI is Visual Glideslope Indicator; among the several varieties found, the PAPI (Precision Approach Path Indicator) is the most common, followed by VASIs (Visual Approach Slope Indicators). You look down at the airport sketch and see a “P” to the left side of Runway 19 threshold and confirm in the airport data that there’s a four-light PAPI. You check NOTAMs (which you also haven’t done in months) and find nothing about the PAPI.

Then you check the RNAV 1: “When circling to Rwy 19 at night, operational VGSI required, remain on or above VGSI glidepath until threshold.” Clearly, there’s something out there to hit.

You wonder what else you might have overlooked. The Chart Supplement for I68 lists for Runway 19 an “8 ft. fence, 305 ft. from runway.” The takeoff minimums for I68 also lists, among other things for the departure end of runway (DER) on 1: “…terrain and tree beginning 36′ from DER, 320′ left of centerline, up to 50′ AGL/958′ MSL…Trees beginning 2001′ from DER, 83′ left of centerline, up to 100′ AGL/1015′ MSL.” Trees are everywhere, and you realize you’ve never read the takeoff minimums for the approaches there—which, by the way, include the “T” to alert you that there are obstacles to watch for. Oops.

You take another look at the chart and notice a lot of close-in obstacles between XODJI and the threshold. “Shudda seen those,” you muse.

Just for giggles, you then check Wauseon, where the RNAV 27 note says: “When VGSI inop, Straight-In/Circling Rwy 27 procedure NA at night.” Oops, didn’t see that one either. Maybe you shudda been checking those.

You’re now sure you flat out busted the regs as you flew the approach without the VGSI. Your friend, trying to stay legal, cancelled IFR just after OSDIE at 3000 feet, flew the last few miles and landed under VFR, using the approach guidance for a stable flight path (he assumed was) clear of obstacles.

This might have worked, except for the VFR-required 500-foot clearance beneath clouds—which he couldn’t see—and the report of a 2300-foot ceiling. That’s enough gotchas to go around. While nothing bad happened, and you probably won’t be getting a letter from the FAA, you’ve learned a big lesson about watching for the not-so-obvious stuff.

Why the VGSI

The FAA urges airport managers to review their instrument approaches for unlit obstacles that penetrate what should be a protected area (on a 20:1 slope) 200 feet from the runway threshold. If found, immediate NOTAMs prohibiting night landings were required.

If there’s an unlit penetration in that protected area, TERPS requires visibility “not lower than 5000 RVR or 1 SM” and there must be a note “to deny the approach or the applicable minimums at night.” However, this requirement also says a VGSI “may be used in lieu of obstruction lighting” with FAA approval. (Over 930 runways feature PAPI and they have been replacing VASI systems.) So clearly, an inop PAPI would cancel the allowance for a night approach, and for good reason.

While glossing over familiar approaches is common, it’s a bad idea. Not only do you miss important stuff, but things change. Obstacles could be lurking closer than you realize when coming home in the dark of night.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. Seems like wherever she flies approaches at night, the trees like to get in the way of a perfectly good glideslope.