Having been very happily married for a long time, my wife and I partially attribute our success to recognizing each other’s pet peeves. Examples? She hates it when kitchen cabinets are left half-open or dining chairs aren’t pushed in, so I ensure that doesn’t happen. My home office may appear, well, unkempt, but I know where everything is, so she knows to leave her organizational tendencies at the door. These minor actions and expectations help maintain a healthy, happy household.

The relationship between pilots and air traffic controllers functions similarly. Through experience, education, and real-world training, we learn the other’s expectations and requirements, and strive to achieve a mutually beneficial operation. Knowing what your counterpart needs, minimizes aggravation and complications.

Some pilots, however, don’t get that. Maybe they just lack some awareness of ATC’s needs or responsibilities. Instead of reducing complexity, these folks compound it by not telling us their plans, or showing impatience when a situation demands the opposite.

Silence isNotGolden

An Airbus A320 was number one in a tight sequence of four airliners. I’d descended him from 10,000 to 2000 for the visual approach and told him to maintain his present speed. I worked some other traffic, and when I came back to him, I saw that he’d leveled off at 5000 and was shedding airspeed fast. I asked him, “Verify you’re descending to 2000?”

“Oh,” the pilot replied, “we needed to level off at 5000 for a minute and slow down.” Okay, so he ignored both the descent and the speed. The other airliners in trail were now not only below him, but faster and rapidly catching up to him. This put everyone—myself and the other aircraft—in an awkward spot.

I was cornered. I assigned him 5000, vectored him off the final, and around into fourth place. I don’t issue “penalty vectors,” but I wasn’t left with much of an out. It’s okay that he needed to level and slow but not saying anything beforehand caused trouble. Had he advised me earlier, I would’ve slowed everyone behind him to match speeds, or vectored them for additional space.

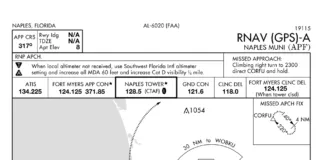

Let’s look at AIM 4−4−10.d., Adherence to Clearance: “When ATC has not used the term ‘AT PILOT’S DISCRETION’ nor imposed any climb or descent restrictions, pilots should initiate climb or descent promptly on acknowledgement of the clearance.” It then goes on to say: “If at any time the pilot is unable to climb or descend at a rate of at least 500 feet a minute, advise ATC. If it is necessary to level off at an intermediate altitude during climb or descent, advise ATC…”

Yup, just let us know what you need. If you can’t do what ATC assigned or need alternate instructions, please just say so. We take action based on available information. Pilots who keep quiet create issues, either for themselves or others. Or both.

Last Second Shenanigans

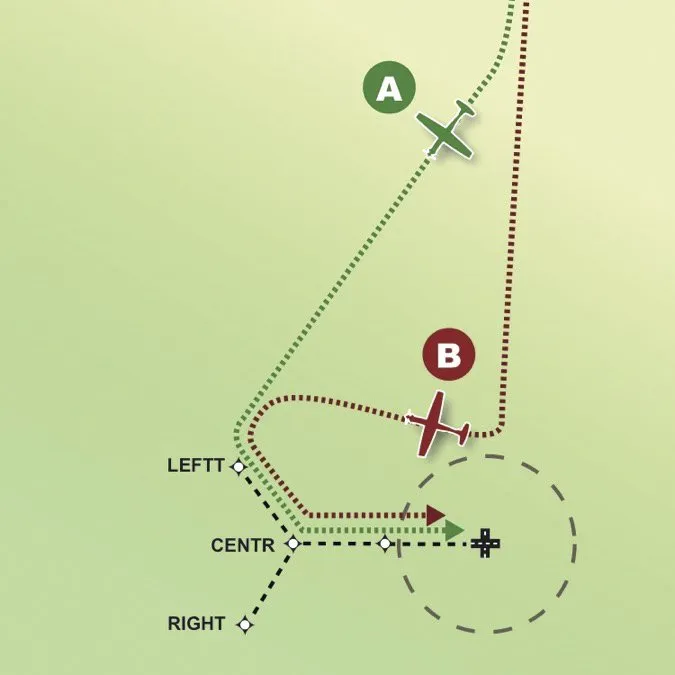

Above, a relatively minor withholding of information changed the picture considerably. What kind of impact do more significant situational changes have on workload? Let’s picture this: you’re on final to Runway 9. You were told to proceed straight in and cleared to land. You’re fully configured and stable a quarter mile from the threshold.

Suddenly, Tower says, “Cancel landing clearance. Enter right downwind Runway 18. Number two following Mooney, two mile final. Cleared to land, Runway 18.” Okaaay, power on; positive rate of climb to pattern altitude. Gear up; flaps up. Find the new runway. Angle for the downwind. Look for the Mooney. Settle into downwind. Adjust speed and flaps again. Turn base behind the Mooney. Reconfigure. Get established on final. Hopefully make it a good landing.

That one transmission forced you to take many actions in rapid succession during a critical phase of flight. I call that, “Not cool.” From a controller’s safety perspective, it’s not good practice to put pilots in that kind of position; last-minute scrambling like that can lead to errors or omissions in procedures.

Receiving those kinds of surprises isn’t fun for ATC either. I was working our East radar sector, vectoring a King Air for a visual approach. He was ahead of a trio of jets, so I’d hooked him in tight toward the airport. After I cleared him for his visual five miles from the runway, he casually noted, “By the way, we just want to do a touch and go and pick up our outbound IFR flight plan to [airport] on the climb out.”

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot! He’d flown 30 miles through my airspace, and just now decided to mention this? Nothing he’d filed suggested anything but a full-stop landing. There was no time to gripe. I needed to coordinate with three other controllers to make this happen, and still needed to work my traffic, including the three jets behind the King Air.

I called our Local (Tower) controller via landline: “Local, East. King Air 123AB’s going to do a touch and go and pick up an IFR with the West sector.” I then switched the King Air to Tower and turned jet #1’s base behind him. Next, I needed the outbound clearance. Clearances usually print on the ground controller’s printer in the tower, not downstairs in the radar room. I yelled across the room at my flight data controller, who handles flight plans. “Data, East, find me a departure flight plan for N123AB.” Meanwhile, I cleared jet #1 for the visual and turned jet #2’s base.

Data printed out a copy of the clearance and handed it to me. I verified it and had him pass it to the West radar sector, who was working departures. I cleared jet #2 and turned jet #3. Now, I called West to let him know what was coming his way. “West, East. King Air 123AB’s going to do a touch and go and get his new IFR clearance from you on the go. Data’s passing you the strip.”

I cleared jet #3 and continued onwards. Was I done with the King Air? Crap! No, I’d forgotten to give him climbout instructions. I called the tower back: “Give N123AB heading 320, 3000 feet, and the West freq on the go.”

Controllers do a lot of talking, and only half of that’s on frequency. The rest of the time we’re coordinating with each other. A seemingly simple request may require a lot of legwork. Had the King Air told me his plans earlier, I wouldn’t have needed to rush things and nearly miss an important step. Letting us know your full intentions early helps us, so we can help you effectively.

Share the Road

Maybe you’ve had this experience: you’ve been on the highway, going somewhere fun, and got stuck behind some truck carrying a “wide load,” plodding along well under the speed limit. It’s too big to pass. Mile after mile, you’re stuck staring at its nether regions. However frustrating it is, there’s not much you can do about it. He’s driving perfectly legally and has as much of a right to the road as you do.

If you’re already flying fast-moving jets and turboprops—or intend to in the future—there’s a simple truth: sometimes, you’re just going to have to follow a Cessna 172 or similar slow-mover. Believe me, it’s not easy for us controllers either, mixing “bug smashers” with turbine-powered hot rods. It involves a lot of speed control and vectoring, as well as a good eye for gauging wind correction and closure rates.

As controllers, we do have final say over, well, final sequences. How do practice instrument approaches factor into our priorities? The ATC regulations—FAA Order 7110.65—cover this in 4-8-11. “…Ensure that neither VFR nor IFR practice approaches disrupt the flow of other arriving and departing IFR or VFR aircraft. Authorize, withdraw authorization, or refuse to authorize practice approaches as traffic conditions require.” Practice approaches, as it states, can be denied based on traffic.

To try and appease everyone, though, we offer options to training flights. Imagine a Cessna requests a practice ILS into my major airliner airport. A multitude of jets are inbound and I’d have to delay every single one of them to get the Cessna his request at that moment. Not very efficient. So, I’d give the Cessna a choice: expect a ten minute delay (until the jets land), or he could shoot the practice ILS at a neighboring airport a few miles away.

However, sometimes the slower plane’s just going to be number one. What if the aircraft wants a full stop? Paragraph 2-1-4 of the 7110.65 states: “Provide air traffic control service to aircraft on a ‘first come, first served’ basis as circumstances permit.” What if he’s already taken delay vectors, waiting on a practice approach? Paragraph 4-8-11 adds a note: “The priority afforded other aircraft over practice instrument approaches is not intended to be so rigidly applied that it causes grossly inefficient application of services.”

The Cessna is a customer too. Yet, the snide remarks from so-called professional pilots following them is something to behold. One example of many: a Hawker pilot—who arrived on-scene after I’d already cleared a Skyhawk for an ILS approach—griped the entire time I extended him. He questioned if the C172 was VFR or IFR. (Doesn’t matter. If they’ve been issued an approach clearance, they’re afforded IFR separation.) He kept asking how far out he had to fly. (I’d already pulled his speed so he wouldn’t go too far.) Each transmission dripped with disdain.

Guess what? Paragraph 4-8-11 also says, “Normally, approaches in progress should not be terminated.” I have—and will in the future—cancel many approach clearances and vector slower aircraft for resequencing, usually in drastic situations where I have a sudden flood of fast aircraft. The Hawker only needed to fly an extra five miles or so. Should I cancel an established approach over one jet’s minor inconvenience? Nope, not going to happen.

That big sky isn’t nearly as expansive as it seems, and there are a lot of airplanes in it, each with their own mission to accomplish. Keeping ATC actively informed of your wants and needs goes a long way toward making that a safe and organized operation. At times, you might not get exactly what you want as fast as you want it. On those days, patience and compromise from both you and ATC can help smooth out the rough patches.

What if it Was You in the Hot Seat?

Our North radar sector was pretty saturated with traffic. I was working the flight data position, passing out flight progress strips and updating the weather displays, while keeping an eye on my increasingly busy coworker. He was working arrivals and departures for one of our satellite airports.

A Citation X called me for his IFR clearance at another, non-towered airport in North’s airspace. I issued it and advised him to hold for release. He read it back and said he was number one and ready to go. After a quick, “Standby,” I headed over to North to secure a departure release and a heading for the Citation.

Commotion erupted before I got there. A Challenger jet off the satellite airport lost an engine on climbout. The crew first wanted to return to its departure airport, then changed their mind, instead requesting our main airport (and its longer runways). Our supervisor was on the landline with our tower, getting the crash trucks rolled. Other radar controllers were vectoring and slowing inbounds to the North sector.

Meanwhile, the Citation X called back. “Do you have my release yet?” North was vectoring the Challenger, while still handling a pile of other arrivals, departures, and overflights already in his airspace. Even before the emergency had begun, he’d already been running close to capacity. The last thing he needed was another airplane in the air. I advised the Citation, “Emergency in progress. The controller is saturated at the moment. I will keep you advised.”

He kept chiming in every minute. “What’s the status? Can we go yet?” I gave him the same answer each time: “I will keep you advised.” He changed tactics after a few tries. “What if we depart VFR and got our clearance in the air?” I told him it wouldn’t work either, since it would be the same departure controller either way. He wasn’t happy with that.

I don’t know if his client in the back was complaining, or if he was already running behind schedule. I just kept thinking to myself: perhaps a little perspective was needed. What if he was the one with the emergency? Would he want someone distracting an already busy controller who could provide him the assistance, information, or resources he needed? Or, would he want any additional aircraft to be kept on deck for a moment until everything stabilized?

About 10 minutes passed before things settled down. North at last gave me the Citation’s departure release, and when I issued it, a different pilot responded. He was far more pleasant than the one with whom I’d spoken. Perhaps they at last realized the delay was not for our amusement, but to keep their flight from taking off into a volatile situation.—TK

Jets? Props? Jetprops? Tarrance Kramer mixes them all while working traffic out in the Midwest.