Things are getting busy approaching Trenton, Tennessee, Gibson County (KTGC), even though it’s not that bad. But the skies are grey enough to make you squint as you enter the overcast. You’ve also entered, as you’ll soon find out, the murky realm of the regs. A cold crust of rime clings to the aluminum and probably the antennas, so you’re anxious to get into that toasty hangar at TGC. Worse, the sun’s going down and the gyro’s acting up. So any shortcuts (safe and legal, of course) would be great right about now.

A Couple Problems

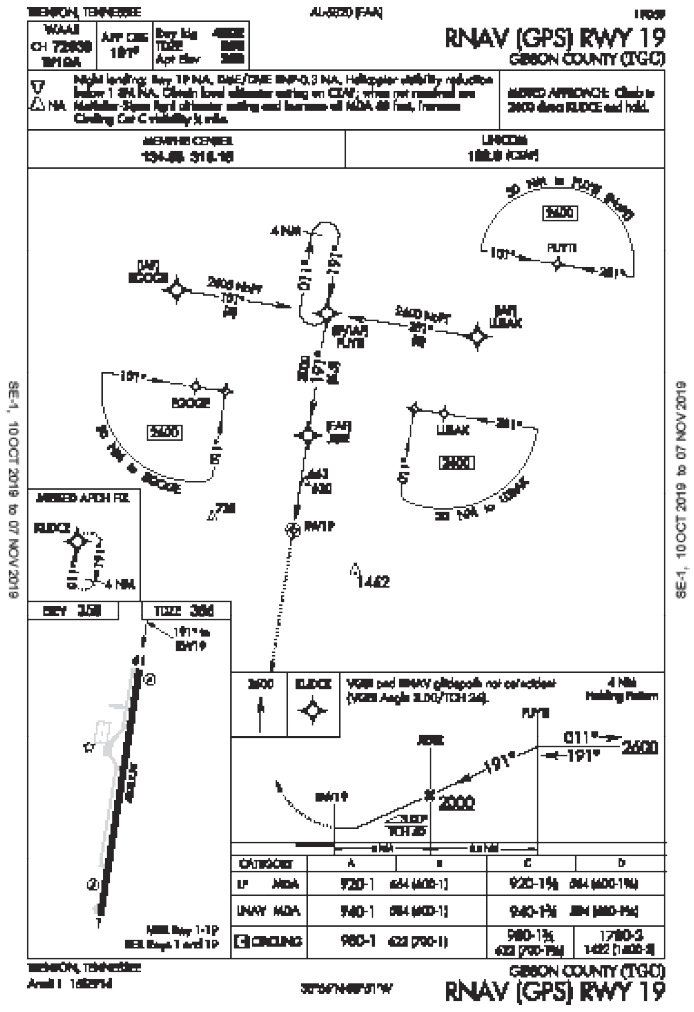

Multiple layers lie between you and Runway 19 at KTGC. The clearance to descend into the first solid layer at 5000 for the RNAV approach is where the icing started. But you’ll press on down, knowing there will be periodic relief between layers. Below that, it’s 1700 and 900 feet broken to scattered, with the lowest clouds scattered at 600, visibility 2.5 miles—you think. There’s no weather station at Trenton, just an altimeter setting on CTAF. Usually, this is more of an inconvenience than a problem; the backup weather information is at McKellar-Sipes Regional 20 miles to the south. There it’s 700 scattered, 2.5 miles visibility. Also nearby are automated stations at Carroll County, reporting similar layers overhead with the lowest reported 600 feet scattered, and Dyersburg, 1000 overcast.

Now, as you put an AWOS on TGC’s wish list, you figure there’s a chance of getting the runway in sight after reaching the final approach fix, JISIR, at 2000 feet, then heading for LNAV minimums of 940 feet—about 580 feet AGL, hopefully under the clouds. In fact, this is a perfect time to use the dive-and-drive method to minimums. Just be mindful that the artificial horizon began lilting a few degrees left since passing through Memphis. Should you have diverted to Fayette County or McKellar? Perhaps, but it wasn’t an emergency. And you didn’t expect the icing.

You’re now arriving from the southwest with a 20-knot tailwind, planning direct EGOGE for the approach. But with the weather and equipment problems, vectors to a seven-mile final might be faster. Also, more talking to keep the radio functionality in check seems the way to go. You decide on full disclosure (91.183) and report the rime, a possible gyro malfunction—manageable for now—and prepare for the straight-in. Still, it’ll be a good 10 minutes, costing precious daylight and lift.

Do I Follow Roads?

To hurry things up, you could cancel if the single runway comes into view, then blast on in as low and fast as you dare: Follow the railroad on the downwind and hang a right. But you don’t know for sure if you can keep the field in sight, remain comfortably clear of the numerous obstacles and remain clear of clouds while staying legal, which means flying low enough to be in uncontrolled airspace (1200 feet AGL until reaching the Class E transition around the airport, then 700 feet AGL from there.) Besides, you won’t know the actual cloud conditions at the field until you arrive. A gut check’s telling you it’s surely not the time to cancel early.

How ‘bout a straight-in to the RNAV 1 from your southwest position, then circle to land on 19? Circling mins are 980 feet, which could end up keeping you in a cloud layer. Keeping it legal is again, not assured. (Chart note: “Night landing: Runway 19 NA,” so time is of the essence.)

Can this be a visual approach? If the clouds around Trenton are higher or more scattered than reported elsewhere, you could get sight of the airport during an approach and switch to a visual clearance once you can remain clear of clouds. However, the airport must have minimum weather of 3SM and a 1000-foot ceiling, which is iffy at this point. ATC’s rulebook (FAA Order 7110.65) also says that the controller must “ensure that weather conditions at the airport are VFR or that the pilot has been informed that weather is not available for the destination airport. Upon pilot request, advise the pilot of the frequency to receive weather information where AWOS/ASOS is available.” Those frequencies you’ve got; you just don’t have assurance of visual weather.

Try This

There is yet another option, the contact approach—that little-used IFR clearance that, while strict with the rules, does offer a shortcut to the runway without a full-blown instrument procedure. Chapter 5, Section 4 of the AIM says that only the pilot, never ATC, can propose a contact approach. If so, you’ve gotta have 1SM visibility; you’ve gotta remain clear of clouds (while remaining clear of obstacles, of course). The airport doesn’t have to be in sight to be cleared, but it’s gotta have a working instrument approach. And the pilot’s gotta “reasonably expect to continue to the destination airport in those conditions.”

If all the gottas (or gotchas) are checked off, the contact approach clearance includes altitude restrictions for traffic separation, instructions for going around and calling ATC back if need be, plus how to cancel after a handoff to advisory. Since you’ll be in charge of your own terrain/obstacle clearance, it’s also a smart idea to have the RNAV IAP active (For more on contact approaches, see “Sneak in the Side Door,” in July 2019.) All this, if it gels, gives you the option of a beeline to Runway 19 while still IFR (you ditched that circling idea a few miles back). Then, especially if ATC has a heads-up on the plan, you have a quick way to convert the approach to a contact and exit the ice with a gimpy artificial horizon. Just beware of the obstacles not far below when passing the final fix.

Coming in on a wide right downwind with a vector of 040 at 2700 feet, you actually see the runway for a few seconds—not required for the contact, but it’s comforting. You’re ready to go for it abeam JISIR, which means you can get down early to 2000 feet, turn onto final early, and drive it to 940 feet til’ you know you’re clear of final obstacles. A PAPI has never looked so good.

Having get-home-itis, ice, and equipment issues all at once really wasn’t the best time to experiment with a little-used procedure in uncertain weather. But in a pinch, a clear understanding of all the legal options can be good start to figuring out the best way in. Then the big decision is about what’s safest, hopefully without further clouding your judgment.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where most of the obstacles have been knee-deep in snow since Halloween. She’s been living on bags of uneaten candy while waiting for the ice to clear out.